When I was in high school in the late 1970s, someone lent my father a copy of Bilingual Today, French Tomorrow. The book is now mostly forgotten, but at the time it circulated widely in English Canada. The author, a retired naval officer named Jock V. Andrew, argued that Pierre Trudeau’s policy to increase bilingualism in the federal civil service was simply the first step in a larger plan to turn Canada into a completely French-speaking country. The prominent aeronautical engineer Winnett Boyd, who believed that Andrew’s thesis was “difficult to refute,” provided the foreword.

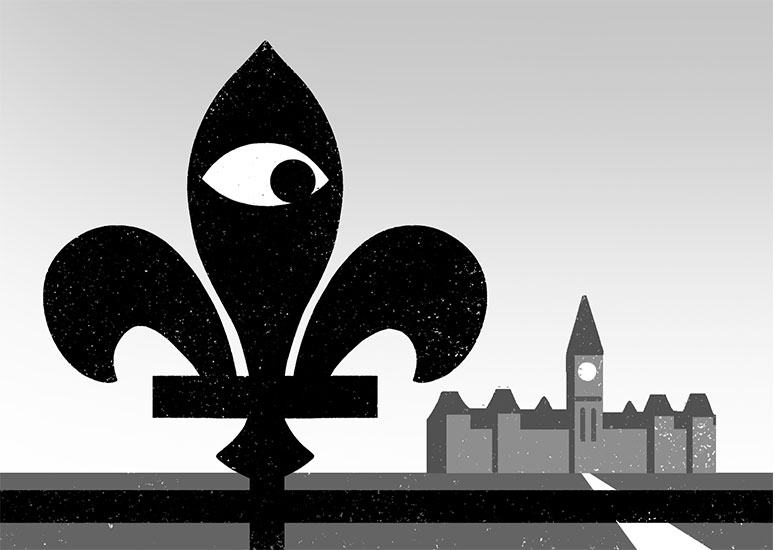

The slim volume, with a giant blue fleur‑de‑lys on its cover dominating a red map of the country, sat on my father’s chest of drawers for about six months before it disappeared. Either he returned it to its lender or my mother, who was born and raised in Quebec City, found a way to dispose of it. I don’t think my father ever looked at it. He was not much of a reader, and he was not a gullible man. But he did have a visceral dislike of Trudeau and an inherited suspicion of Quebec. Like many Anglo Canadians who enlisted during the Second World War, he deeply resented the prime minister’s avoidance of military service and opposition to conscription.

Not available in bookstores, Bilingual Today, French Tomorrow had to be ordered directly from the author, for $3.50. Still, it sold more than 120,000 copies in its first year. These copies, in turn, were widely shared among friends and family. The informal circulation anticipated the way misinformation often spreads on the internet — unimpeded by media filtering, below the public radar, and away from critical scrutiny.

Andrew’s claims were taken up by some of those whom Stephen Harper would later describe as “old stock Canadians”— citizens of British heritage who saw Canada as an English-speaking nation that was politically and culturally linked to the U.K. This group had assumed that the French-speaking population centred in Quebec would continue to play a minor role in national politics and, in due course, would become assimilated into the more successful political and economic culture of English Canada. But in the late 1960s, with the election of Trudeau and the escalating debate about Quebec’s role in Confederation, this assumption had become more difficult to maintain.

Clandestine attempts to keep English Canadians out of power?

M.G.C.

Bilingual Today, French Tomorrow tapped into the concern that many Canadians had about the increasing visibility of the French language in the country’s commercial and political life. At the time of its publication, in 1977, there were loud complaints that French was being “shoved down our throats,” after the government required manufacturers to include both official languages on product packaging. The increased visibility of French coincided with Ottawa’s affirmation of multiculturalism, which recast cultural diversity as something to be celebrated, rather than as a problem to be managed. The official recognition of both bilingualism and multiculturalism represented a challenge to the Anglo Canadian understanding of national identity.

Andrew sought to expose the deeper and disturbing purpose behind bilingualism. He was convinced that a secret plan had been carefully worked out long ago by a cabal of powerful French Canadians and was now being implemented through careful political manoeuvring by Trudeau and his secretary of state, Gérard Pelletier, with the help of a fifth column of “goons.” Andrew maintained that Trudeau, “under cover of some very clever double-talk,” had set out “to convert Canada from an English-speaking country into a French-speaking country.” Official bilingualism was “nothing but a smokescreen for what is really happening.” This conversion was “the primary and sole objective” of the government, and would “remain the same until every city, town and village in Canada has become French-speaking and French-controlled.”

Trudeau had employed specific strategies, Andrew contended, to bring about this transformation. The most important: the requirement that all significant positions in the federal civil service, the armed forces, and the RCMP be held by individuals who could speak both languages. This, supposedly, would ensure French Canadian control of critical national institutions. It was a simple and obvious fact that they were far more likely than English Canadians to be bilingual, since the latter previously had little reason to learn French. The larger plan also included changes to immigration policy that disfavoured those from Britain but welcomed newcomers from French-speaking countries, as well as government support for the internal migration of French Canadians within the country.

Now that Quebec had “for all practical purposes removed all vestiges of the English language” from its territory, it could serve as “an impregnable bastion, breeding pen, and marshalling yard for the colonization of the rest of Canada.” Once they were resettled in English-speaking communities, the new arrivals would be encouraged to demand services in French. This secret operation was being implemented with the “organizational assistance of the French Church, and under cover of an organization called the Richelieu Society.” Andrew also pointed to “paid agitators (officially termed ‘animators’)” who were “inciting French-Canadians to militant racism” and demanding services in French from every level of government. He was confident that once English Canadians woke up to what was happening, they would resist the Trudeau plot with all the resources available to them. And because the plot was so far advanced, violence — even civil war — might be necessary.

Conspiracy theories seek to expose hidden forces that lie behind significant events or social developments. Occurrences that on the surface appear to be the consequence of natural or social forces, or the actions of one individual or a few, are instead the result of carefully laid plans by powerful individuals, whose involvement has been actively concealed from public view. While these theories have a common character or structure, their content is culturally specific, reflecting the issues and anxieties of a particular time and place, which in the case of Bilingual Today, French Tomorrow (and Andrew’s 1979 follow‑up, Backdoor Bilingualism: Davis’s Sell‑out of Ontario and Its National Consequences) included the historic distrust that many English Canadians held for Catholic Quebec, and a general anxiety about growing ethnic and racial diversity. Most of the conspiracy theories that originate in the United States rest on an intense distrust of government (and in particular the “deep state”). Andrew, in contrast, did not regard state power as inherently corrupt but was instead concerned with the usurpation of that power by those working against the public interest.

Many of the best-known theories, such as the deep state’s responsibility for the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11 or the assassination of John F. Kennedy, reject the established account of an event and purport to expose its true cause. These are not simply backward-looking explanations, however. They understand the conspiracy to be ongoing — involving the active and continuing concealment of the truth and the suppression of evidence that contradicts the official story. And, of course, it is understood that conspirators with enormous power and influence (whether the deep state or the pharmaceutical industry or the Illuminati) are continuing in their efforts to manipulate events.

Bilingual Today, French Tomorrow was different. Because the conspirators’ objectives had not yet been realized, the book was both an exposé and a call to action. In this way, it resembled The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an anti-Semitic pamphlet, produced at the end of the nineteenth century, that purported to be a first-hand account of a Jewish plot to undermine Christian civilization. Similarly, some versions of the “Eurabia theory,” which anticipates the domination of Europe by Muslims, claim that a secret agreement has been reached between powerful European political and corporate interests and leaders of the Muslim world. (This belief has inspired numerous violent acts, including attacks on mosques in Quebec City and Christchurch, New Zealand.)

When large groups of individuals feel vulnerable to forces beyond their control, conspiracy theories flourish. They trade on a distrust of authority or expertise — a distrust that has sometimes been cultivated by political actors and media outlets that are mostly, but not exclusively, right wing. Spin now dominates discourse. Distortion and deception have degraded things, so that we no longer expect to be told the truth and are less able to evaluate the ideas and information put before us. The consequence is that the choices we make are often based not on reasoned judgment but instead on ideological predispositions.

In a sense, conspiracy theories are a modern form of mythology. They offer simple and understandable explanations for complex events that are the outcome of multiple social and natural factors. Believers resist the idea that things happen by chance and instead imagine there are always larger powers at work — and those powers may be malevolent. When people’s lives or expectations are disrupted in a dramatic way by a major social or natural event, they may find it difficult to accept things as simply random or accidental. These theories tell stories in which ordinary people play central roles. The forces that have disrupted their lives are not indifferent to them. The conspirators thought about them, took them into account, and acted in order to harm them. Within this framework, people’s anger is justified and has an object. It is possible for them to resist the villains — to oppose the conspirators’ plans or to expose what they have done.

Conspiracy theories especially appeal to individuals who fear the loss of social status or economic security. And because status is often tied to national or racial identity, these accounts are often explicitly xenophobic or racist. They direct people away from the complex sources of their economic and social difficulties, and toward identifiable people or groups who are accused of plotting to undermine the status quo — whether Protestant English Canada or Christian civilization.

Suspicion of authority makes conspiracy theories remarkably resilient. Counter-arguments and inconsistent facts are simply absorbed, providing further evidence of the power of the conspirators and the breadth of their scheme. Unlike most theories, though, the one advanced in Bilingual Today, French Tomorrow could be disproved with the passage of time. Andrew had claimed that the conversion of Canada into a French-speaking country would occur within ten years. Clearly that did not happen. Yet his most ardent followers, including members of the Alliance for the Preservation of English in Canada, were not completely discouraged. Some simply adjusted the theory, so that it was now about French control of the levers of political power, rather than the full-scale transformation of Canada into an exclusively French-speaking country. Others insisted that the predicted transformation had not come to pass because Andrew had alerted the nation — and thereby foiled Pierre Trudeau’s plan.

Disinformation now spreads easily and rapidly within social media ecosystems that are liberated from filters and counter-argument. In such a world, Bilingual Today, French Tomorrow seems almost quaint. The issues that caused many Anglo Canadians to feel anxious about their identity and status — including changes in Canada’s ethnic and racial mix and the shift in its cultural orientation from the United Kingdom to the United States — did transform this country, although not in the ways that Andrew feared. With these changes have come a new set of anxieties and identity issues that are sometimes expressed as imagined conspiracies. However, even these theories are now largely generated outside the country and are no longer specifically Canadian in their content.

Richard Moon is a distinguished law professor at the University of Windsor.