Think of the long trip home.

Should we have stayed at home and thought of here?

Where should we be today?

Is it right to be watching strangers in a play

in this strangest of theatres?

— Elizabeth Bishop

On February 29, the calendar’s most elusive date, I arrived in São Paulo from my home in London. Although the morning was cool and overcast, emerging from the northern hemisphere winter into the subtropics felt like awakening from a cryogenic slumber. During the flight, I had watched Orion cartwheel across the sky as we journeyed down the Atlantic Ocean. I am a hardened traveller, but each time I fly I find it a miracle that we are able to propel ourselves through space with such velocity and relative safety. Also, I know how long the alternative mode takes.

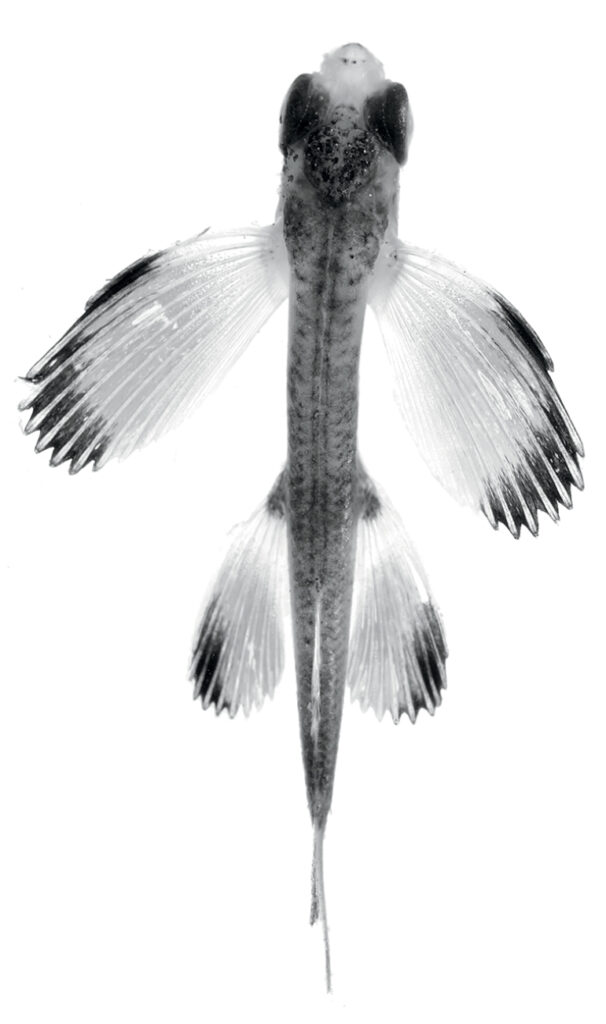

A decade ago, I travelled from the Falkland Islands to Vigo, in northern Spain, on a research vessel — the longest of several trips I have done as writer-in-residence on scientific expeditions. It took us three weeks to sail along the coast of Brazil alone. I remember looking at the charts each day on the bridge, watching the second officer mark our inching progress in a pencilled line filigreed with Xs. Some days, it seemed we stood still. The horizon remained unchanged as we stuttered upward into the tropics, the deck becoming littered with flying fish, which stranded themselves there by the hundreds. There was a stretch when we did not glimpse another ship on the radar for eleven days. More than any other of my voyages by sea, that journey showed me the true girth of the planet — something difficult to apprehend as we zoom around it in the troposphere.

I have always been restless, not to mention claustrophobic. I live in London, in part because it’s an easy city to leave. We have six major airports that process seventy-eight million passengers annually; in normal circumstances, 1,300 flights a day take off and land at Heathrow alone. I’ve benefited personally and professionally from the hypermobility that the city affords. Even when I’m not travelling, I can tag along vicariously. If the prevailing southwesterlies are blowing, I have a clear view from my flat of planes lining up to land at Heathrow. One floats into view every ninety seconds, as if turned out from a factory at precise intervals. There is something serene and reassuring in the way they sink through the lemon haze of the city smog like vast, contented sharks. Each plane signifies an opportunity to leave and gather new knowledge and experience; each is an exemplar of modernity. “Andando más, más se sabe,” wrote Christopher Columbus, navigator and plunderer of the Americas. The further you go, the more you know.

Perhaps the fish are still flying.

Smithsonian Institution

In my obsession with travel, I am probably making that most basic of errors, mistaking movement and velocity for a plan, shape, or purpose — even a morality. The journey is a too-convenient synecdoche for life. Arrivals and departures have a built-in drama, but they are enigmas too, a distraction from the essential marathon of living, which is staying: staying the course, staying put, enduring.

Travel is often tedious and upsetting, never mind dangerous. Over the years, I’ve been snarled in New York, where I found myself underneath the World Trade Center as both planes struck, and then marooned for weeks afterwards when all aviation was cancelled. I’ve been stuck at Toronto Pearson after an Air France flight crashed on the runway, stymied by polar whiteouts in Antarctica, stranded by volcanic eruptions, and abandoned by the Royal Air Force on a tiny island in the middle of the Atlantic. But the pandemic is the most effective grounding I’ve experienced. As I scour the silent London skies for planes, I consider what I have lost or, more precisely, what has been rescinded.

I started reading Elizabeth Bishop’s poetry in part because, like her, I grew up in Nova Scotia, and I felt a kinship with her rendition of its landscape, as well as admiring her remarkable melding of the vernaculars of the natural and the social. I began reading her in earnest in Rio de Janeiro, where I lived in the mid-1990s, and where Bishop had lived many years before.

Like Bishop, I detect a common grammar in the geographies of Brazil and Canada. The two countries are in many ways twins, built on similar continental scales, both totalizing polities that span climates, ecosystems, dialects, Indigenous cultures, remote archipelagos of settler communities, wildernesses ransacked by extractive companies, and time zones. Most Brazilians live in the southern industrial heartland. For them, Amazonia functions in the national imaginary as the Arctic territories do for the bulk of border-hugging Canadians: a near-mythic region that they will likely never visit. Instead, they might venture to Portugal or Argentina, to “experience something different,” as a colleague from São Paulo remarked to me. After hearing of my stays in the Amazon and the northeast, she said, “You’ve seen more of Brazil than I will ever do.”

Elizabeth Bishop arrived in the country by ship in December 1951. She would spend much of the next seventeen years in a place she expected to visit for only two weeks. Brazil fuelled her best poetry, not always as direct inspiration. The physical and psychological distance that the move afforded her seemed to permit her, at forty-two, to finally write about her painful childhood, when she was bounced between relatives in Nova Scotia and Massachusetts. Out of this awakening came some of her best-regarded work, including “Sestina” and “In the Village.”

Bishop grew up partly in her grandparents’ house in Great Village, a tidy settlement not far from the shore of Minas Basin, an arrowhead-shaped body of water in the crux of the Bay of Fundy. Here, famously, the highest tides in the world rake in and out every day, their differential up to sixteen metres — as tall as a five-storey building. Minas Basin is shallow, and the transformation wrought by the vast tidal machine is all the more startling. It makes for a backdrop that is in constant radical motion, a gargantuan sink draining and filling. I wonder if this natural anomaly influenced Bishop’s writing, if not representationally then rhetorically. Her customary recalcitrance, the lines that bristle with questions and corrections: could they be, in part, a consequence of living in a place where even the horizon is unstable? That daily rupture from russet mud flats to the glimmering seams of cold sea may well have sharpened her eye and her sense of indeterminacy.

On arriving in Santos, Bishop noted the port city’s impractical landscape. The mountains of the Serra do Mar, a 1,500-kilometre-long range that runs close to the Atlantic, were “self-pitying,” their greenery “frivolous.” Moving on to Guanabara Bay, she quickly came to the pithy observation that “Rio is not a beautiful city but rather a beautiful setting for a city.” These judgments are abrupt, dismissive, and perhaps a defence mechanism. Possibly, the only way she could get purchase on this wholly unfamiliar reality was to read it through a cool prism of reticence. Her northern hemisphere eye was being challenged; so too was what she would later call her “Scotch-Canadian-Protestant-Puritan” temperament.

I have often thought about the way the original landscapes of our lives become the means through which we interpret the world. My theory is that we imbibe the detail of the places where we grow up, absorbing it into our psyches and bodies in a form of metaphysical transfer. For Bishop, Brazil functioned as a kind of Claude glass, a black, reversing mirror turned on the chilly grandeur of the north she knew. (In one of her earlier letters home, she joked that the place was “a kind of deluxe Nova Scotia.”) Even as her new environment invigorated her present-tense poetry, honing its aesthetic angle of attack, her mind was lured back to the Maritimes of her childhood: those “narrow provinces of fish and bread and tea,” with their lupines, bladderwrack, fireweed, and wild iris.

When I first came to Rio de Janeiro in 1994, I struggled to believe my eyes. The perfect cursive of the Bahía de Guanabara, the mountains with their meringue-whipped peaks, the terracotta favelas that clung to their sides, and the massive, futuristic highway tunnels blasted beneath them. This remains the single most powerful impression of a place I have ever experienced, a sensory overload that took me days to recover from.

Straight away I realized that the lavishness of the tropics presented a mimetic challenge to a writer. Try to describe it and you risk overstatement, sentimental naïveté, and — a more serious flaw — an instinct to exoticize. The natural abundance and warmth are easily romanticized, but the cummerbund that stretches around the planet, 23.5 degrees from the equator north to south, is overwhelmingly a zone of poverty and inequality. Only Singapore, Panama, and a clutch of tax-haven Caribbean islands join the ranks of the thirty countries classified by the World Bank as high income. Brazil itself is currently the eighth most unequal country in the world.

By the time I arrived, Bishop had been dead for fifteen years. As I went about my work as a journalist, I found myself brushing up against her ghost in unsought, fortuitous encounters. Ricardo Sternberg, the nephew of Bishop’s Brazilian partner Lota de Macedo Soares, was the cousin of a friend of mine. One rainy day, I met him at a pizzeria in Botafogo for lunch. I had told him that I was a writer from Nova Scotia living in Brazil and that I hoped to write about his aunt’s partner and her affinity with landscape. Sternberg was then a professor of literature at the University of Toronto. Here was a grown‑up version of the boy I had read about in Bishop’s letters, whom she had helped get from Rio to Harvard, where she would later teach.

“She was very good fun,” he recalled. “Very humorous, an engaging conversationalist, a kind of raconteur.” This was not what I had expected to hear about a person who — if you read her carefully crafted poems as indicative of her personality — might be thought coolly contemplative at best, a fussy perfectionist at worst. She did not behave like a literary figure, he told me. “She never flaunted the fact that she was widely read or exercised her vast range of reference. She could talk to anyone; she would not talk down to them.”

Not long afterwards I went to a churrasco at my friend Marie’s house in Petrópolis, the mountain town where Bishop and Lota had lived in Fazenda Samambaia, the Frank Lloyd Wright–esque house that Lota had built there. Given that thirty years had passed, I didn’t expect anyone to remember her. “The house is there,” Marie pointed across the road. “My handyman, Vidigal, used to work for her.” Within minutes Vidigal was beside me, a figure not unlike the tenant farmer whom Bishop’s alter ego takes to task in “Manuelzinho.” He began recounting anecdotes, unprompted, of how Doña Lota always drove too fast on the twisting, precipitous roads, and how Doña Elizabeth would sit and watch the clouds spiral down from the mountain for hours.

Back in Rio, I reread “Questions of Travel,” replaying the scenes that surrounded me: “The mountains look like the hulls of capsized ships, / slime-hung and barnacled.” I adopted Bishop’s lens, as if donning another pair of eyes, to look upon the city’s unique, stern voluptuousness. The Pão de Açúcar, whose western flank I could see from my window, and the towering Pedra da Gávea were exactly that: upturned freighters, coated with bromeliads and moss dripping in the epic winter rains.

Other encounters followed when work took me to Ouro Prêto, the colonial-era town in the state of Minas Gerais, where Bishop lived out the latter part of the Brazilian chapter of her life. It was there I met her friend (and lover, although I didn’t know this at the time) Lili Correia de Araújo. I then made my way to Santarém, the low-slung, sultry city at the confluence of the Amazon and Tapajós Rivers, and the subject of Bishop’s eponymous poem. I came to feel a bit spooked; her presence was everywhere I went, a persistent, diaphanous chaperone.

Although we are separated by sixty years and by social class, there are striking similarities between our childhoods. Bishop was brought up for a time by her maternal grandparents; I was also raised by my mother’s parents in Cape Breton. Her father died when she was eight months old; I never met my father, although I know now that he is dead. Her mother was committed to a psychiatric institution when she was five, and they never saw each other again. I met my own mother when I was eight, when her true relation to me was revealed, and I lived with her for only a handful of years. Like Bishop, my early life was peppered with stoic great-aunts, mental illness, alcoholism, isolation, and the fragmentation of families who let houses, land, and finally each other slip through their fingers.

Until I was living in Rio, I had no idea that Bishop had written about the place where I grew up. The Cape Breton of her rendering has a mysterious, spectral quality, with mist haunting the fissures of the land, the “rotting snow-ice sucked away / almost to spirit; the ghosts of glaciers drift / among those folds and folds of fir.” She sees abandonment in “deep lakes” reputed to be in the interior — the Bras d’Or Lake, most likely. The baleful land gives way gradually to poignant characters: two preachers, a man carrying a baby, a bawling calf. Here, she perceives the essential bargain of living in wilderness: nature determines and defines you, the land is supreme, and we are subjects in its dominion.

I found this equation stifling. I didn’t want to live in a lifelong state of siege by a domineering wilderness, never mind in poverty. Bar my grandfather, my immediate family were outraged if circumstances — a family visit, a job — required them to leave the island. Our radio was the unceasing stream of visitors that came to my great-aunt’s store and gas station, and the gossip they brought from the outside world. That was enough for them. So where did my restlessness, my conviction that I had to get away, come from?

An early childhood scene: an apartment where we stayed, after fleeing the breakdown of my grandparents’ marriage, on Ochterloney Street — a name that could only have been dreamed up by homesick Scots — in downtown Dartmouth, which was in those days a rustbucket city, Halifax’s poorer twin. I remember nothing about the place apart from colour: a roll of toilet paper, pink or purple, wallpaper that wouldn’t have looked out of place on a Beatles album cover. It was the mid-1970s in the Maritimes, always a few years behind global trends, and the world was still cast in shades of sherbet: avocado bathrooms, magenta bedsheets.

An abstract panic overtook me. I began shaking, very slightly, as if I had a chill. “I have to go,” I said. “Go where?” my grandmother asked, casting around the apartment, confused. “You mean the corner store?” I replied, “Somewhere.” But what I meant was anywhere.

I’d had a premonition. At eight, I understood that we were poor, and getting poorer, and that I was going nowhere, in every sense. I was being lined up by circumstance to serve as one of life’s bystanders, and rightly or wrongly, I concluded that I could dodge this fate through motion. The hunger to move through space that seized me in that apartment has never left. I still feel harassed by the curve of time — an aperture that is about to close and extinguish me — and the harried need to reach a place where becoming, not just belonging, is possible. It is like being addicted not to any substance but to a dimension.

Bishop explores the relationship between spaces and solitude. (Although rarely alone romantically, she said to her friend Robert Lowell, somewhat melodramatically, never mind grandiosely, “When you write my epitaph, you must say I was the loneliest person who ever lived.”) A latent restlessness courses underneath the surface of plangent questions: “Should we have stayed at home and thought of here? / Where should we be today?” In many of her poems about place —“The Map,” “The Imaginary Iceberg,” “Night City”— she approaches her subject from a distance. Here, emotional situatedness requires separation.

Now, distance and isolation have invaded our everyday language. I had never heard of “self-isolating” or “social distancing” until a few months ago, but our lives have since become soaked in such bizarre phrases. Like so much of the novel coronavirus discourse, these are lonely terms. Rereading Bishop’s work in so‑called lockdown (another example), I am more struck than ever by how many of her poems are cloaked in an atmosphere of loss, even those she wrote in her youth. The sound of elegy is anticipatory, even prescient, as in “Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance,” whose ironic title is undercut by the first two lines: “Thus should have been our travels: / serious, engravable.” In the echo chamber of her work, “One Art” stands supreme for loneliness and lament: “I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster, / some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent. / I miss them, but it wasn’t a disaster.”

Speaking of disasters and engravings, the cover of my diary enthusiastically states, “2020 — Filled with plans, parties, and plots to conquer the world.” How could I not have heard the fate-baiting message, the hubris?

The diary currently leads a much more interesting life than I do, having already been, or being about to travel, to Jordan, Kenya, Zanzibar, Spain, and Canada. Since escaping the flat on Ochterloney Street, I have spent much of my life commuting between hemispheres. My existence is oriented and organized emotionally through motion. Like a compass, I point myself in the direction of the next place, the people I will meet, the alchemy of possibility. Movement gives fission to what I think of as the defining element of life: entropy.

Travel, of course, represents both privilege and damage. As someone who has researched and written three books on the polar regions, I have seen the three square metres of ice shrinkage caused by each one-way transatlantic flight. In the context of the collective trauma of the pandemic, this pause in our plans is not a serious problem. Yet, to be confined by governments, even if required to fight a deadly virus, is to be disempowered, politically and economically. And for a writer, it restricts the basic premise of our role in the world: to bear witness.

The loss of the usual crochet of contrails over our skies is a potent symbol for how I have experienced the outbreak. The stillness signals an abrupt and disorienting collapse of time and space. This stage of my life, previously so global, has shrunk to the four square rooms of my flat. Now, I am effectively more trapped than I’ve ever been on Antarctic bases during whiteouts, or on ships in the middle of the ocean with engines on the blink. I find myself living under a version of martial law in a country that has seen some 50,000 excess deaths so far, and whose government’s negligence, bluster, hesitation, and rank errors are becoming increasingly clear. Brexit and the pandemic response are intimately connected, both products of arrogant complacency and misguided exceptionalism. I think of them now as a joint venture: PanBrexit, Brexdemic. In any case they are both termini: first we were held captive by nationalism, a program of disjuncture based on the denial of possibility, identity, and opportunity. We have since become hostages of another, more literal death.

Being in quarantine feels very much like one of my long sea voyages. There are dark clouds to the north, dark clouds to the south. The days are gelid with a sense of waiting to arrive, waiting for the succour of harbour. All islands are islands; for once, the oceans and the whales that ply them are relieved by our sudden silence. We are under-occupied, spooked, stalled, and suddenly fanatical about details that used to not preoccupy us. We wait to resume life at our own pace. I have a realization: it’s not just restlessness that compels me to travel, I feel safer while in motion. Here in my flat I feel like a sitting duck, as if I’m waiting for the virus to find me. I’d rather take a risk and venture out into the world and all its mortal glamour.

“Is it lack of imagination that makes us come / to imagined places, not just stay at home?” Bishop asks at the end of “Questions of Travel.” A similar bewildered voice in Geography III wishes to know, “In what direction is the Volcano? The / Cape? The Bay? The Lake? The Strait?” The bristling question marks are mine, now.

What would have happened on the journeys I have had to forsake this year? In Jordan, I was to interview pharmacists about a new vitamin formulation. In Zanzibar, I would have taught a non-fiction workshop to young writers from across Africa. In Tanzania, I had arranged to interview Richard Knocker, one of the top safari guides on the continent, for a book I am writing on the Anthropocene. I conjure a montage of my counter-life: slim ngalawa boats, the fishing dhows of the coast of East Africa, their only light at night a hurricane lamp in their bows; low clumps of Acacia mellifera, the blackthorn tree, on the lip of the vast inland sea of the Ngorongoro; the ochre plains of Jordan seen from the window of a plane banking to land.

As Columbus understood, the spirit of travel is the same as that of knowledge. To go to an unfamiliar place is to enter into a similar state of high alert as that required for interpretive and imaginative writing. The journey always involves a quest, the acceptance of multiple perspectives and contingent realities. The voyaging self is always aware of the life of its twin, the might-have-been self, had we stayed at home. The pandemic has disrupted our equation between place, being, and possibility, especially those of us with multiple nationalities and identities. My home is everywhere, and so staying still is a paradoxical form of homelessness. Perhaps, as for Bishop, literature is my true home.

Today, for the first time in eight weeks, an airplane arced overhead. The sound of its deceleration, like the groan of an exhausted angel, once so familiar, is now deafening. I rushed to the window — a British Airways A320, on quick inspection. It looked less like a plane than a visitation from another dimension. I watched as it banked to the west, finding its waypoints to the runway.

When I returned from Brazil in early March, I couldn’t have foreseen that it would be my last journey for a while. I couldn’t have imagined the empty terminals, their luxury shops shuttered, or the couple of hundred passengers shuffling through in hazmat suits and plastic face shields, wiping down their luggage with Dettol.

By March, the virus had made landfall in Britain. I had seen a few people wearing masks when I flew from São Paulo to Porto Alegre, but otherwise everything had looked normal. As I finally wheeled my suitcase through Terminal 5, I stopped for a moment to admire its vast cathedral-like interior, the maze of orderly BA check‑in desks, with people snaking between them wearing saris, keffiyehs, dashikis. It was the world in miniature.

On the customary Piccadilly Line purgatory — slow, but less than a quarter of the cost of the stupidly overpriced Heathrow Express — I recognized one of the cabin crew across from me, an Irishman with an alarming sunburn (he had fallen asleep around the pool, he said). I asked about his pattern of working, why he did the job. The long-haul flight to São Paulo was outside of his routine, he told me. He usually did the routes to Boston or New York, although his wife would prefer him to stay within Europe.

What kept him doing these kinds of journeys? Surely it was difficult to be so far away from home and family? “I never get tired of travelling,” he said. “Maybe there’s something wrong with me, but if I couldn’t do it, I’d be so depressed.”

At Hatton Cross Station he bounded off the Tube on his way to catch a flight to the west coast of Ireland. I wished him a good trip as he waved goodbye, his burned face gleaming in the light of an early spring morning.

Inspirations

Elizabeth Bishop

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1965

Elizabeth Bishop

Selected and edited by Robert Giroux

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994

Jean McNeil has recently published Day for Night.

Related Letters and Responses

Ricardo da Silveira Lobo Sternberg Toronto

Jean McNeil London