Tim Cook has spent the last two decades publishing well-received, accessible accounts of Canada’s military history. Much of his early career focused on the First World War (his Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1917–1918 won the 2009 Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction). More recently, he has written poignantly about that war’s successor, including his two-volume The Necessary War and Fight to the Finish. His latest book, The Fight for History, positions the Second World War on the periphery of larger questions: What does it mean to remember, and why is history so important to our national well-being?

Ask Canadians what they know about their country’s military history, and most will mention Vimy Ridge. That 1917 battle marked the first time that all four divisions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force attacked a target together. Its success, often attributed to the planning prowess of the division commander Arthur Currie, has since become symbolic for many of an emerging independent national identity. But ask more specifically about the Second World War, and you’re likely to draw a blank. Intuitively, the disparity is baffling. For one thing, thousands of veterans still live among us. Moreover, if there has ever been a good or “necessary” war, to use Cook’s term, the conflict that successfully prevented a savage and evil Nazi regime from taking over the world would have to be it. So why, until relatively recently, has it been so poorly remembered in Canada? The Fight for History provides a series of answers that are as worrisome as they are convincing.

Cook begins with the veterans themselves. When the Second World War ended seventy-five years ago, many felt that they had “earned their peace dividend.” Now was the time to build a better future for themselves and their families, rather than to dwell on what they had seen and felt overseas. Ironically, the Allies’ victory dulled the wartime horrors in the popular imagination. When Mackenzie King rejected calls for a new national monument to commemorate the sacrifices made abroad, the prime minister effectively dismissed the limited veterans’ protests that did emerge and suffered no political consequences.

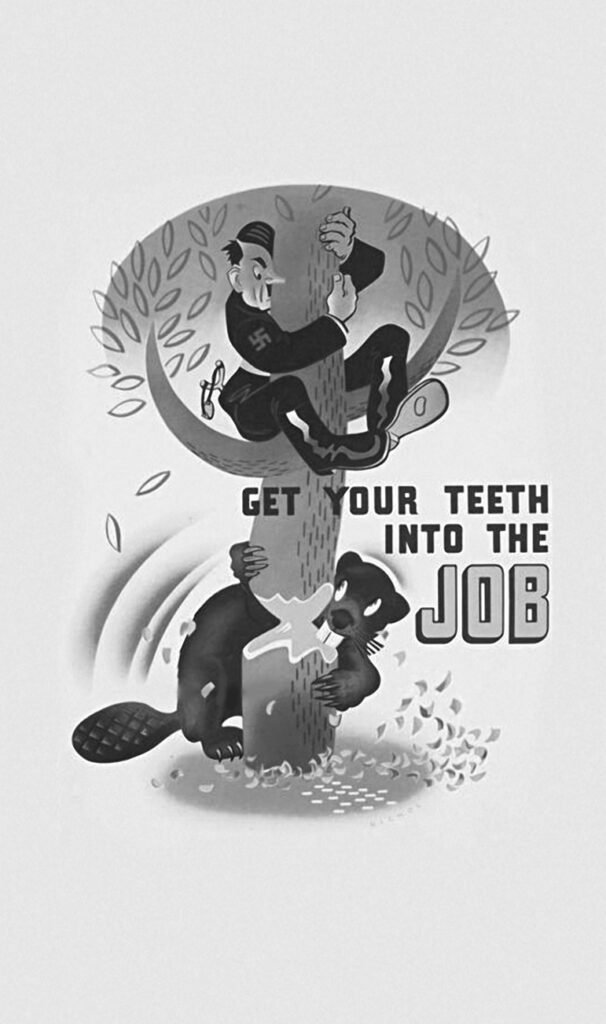

There’s still a battle to be fought.

Wartime Information Board; Library and Archives Canada

The rapid and aggressive demobilization of the armed forces that followed was similarly palatable to a citizenry that had moved on from its wartime posture. In the aftermath of significant cutbacks to all three military services, Cook notes, “the senior officers found the pen-wielding uniformed historians easier to target than the traditional military personnel heading into the new Cold War.” While work on the army’s official history continued, efforts to capture the stories of the air force and the navy were compromised. And, unlike their Allied counterparts, few senior Canadian military leaders wrote about their personal involvement. The National Film Board and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation weren’t much help either. It took seventeen years for the NFB to produce the highly regarded Canada at War series. Few watched it, though, as the CBC screened its episodes late in the evening. Since most veterans were inclined to limit discussions of their experiences to private Legion halls, those still interested in what had happened inevitably turned to American and British sources.

If the first fifteen postwar years reflected what Cook calls “benign neglect” in the recording and recalling of Canada’s wartime experience, the next fifteen were plagued by open hostility. Many veterans, still clinging to old British traditions that were quickly eroding in modern Canada, interpreted the 1965 adoption of the Maple Leaf flag as a personal affront. American involvement in the Vietnam War poisoned thinking about violent conflict among a growing number of young Canadians, many of whom couldn’t, or wouldn’t, differentiate between a war in defence of freedom and a military quagmire. Under the spell of the Quiet Revolution, nationalist Québécois officials responsible for the provincial high school history curriculum transformed the country’s wartime activity into proof of “English Canada’s subjugation of French Canada.” For young Quebecers, the war became a story of Canadians being sent to their deaths by incompetent British generals, while systemic discrimination held back the career progression of francophone officers. Mackenzie King’s 1944 decision to impose conscription came to symbolize the ultimate betrayal of French Canada by its English brethren.

Elsewhere, Canadians were hardly lining up to defend the state’s wartime conduct. The late 1970s marked the beginning of a national awakening to the forced relocation of thousands of Japanese Canadians in the early 1940s, a tragedy made more widely understood by the publication of Joy Kogawa’s novel Obasan, in 1981. Rather than acting quickly to acknowledge the wrongdoing, Ottawa stalled. Only after the United States Senate announced its commitment to restitution for Japanese Americans, who had been similarly mistreated, did the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney pledge $400 million in compensation and promise to teach and disseminate this terrible story.

Cook’s assessment of Ottawa’s actions is irksome. While he recognizes the harm done to Japanese Canadians, he reserves his vitriol for Tokyo’s refusal to acknowledge its horrific mistreatment of Canadian prisoners of war. A subsequent chapter that details the belated official recognition of Indigenous veterans and members of the merchant navy is more balanced. Taken together, these chapters convincingly demonstrate that, hardly forty years after one in ten Canadians donned a military uniform to defeat one of the most tyrannical and vicious dictators of the modern age, pride in the national contribution to the Allied effort had been all but replaced by shame over the country’s domestic failures.

Cook reserves his harshest criticism for The Valour and the Horror, a series of three films released in 1992 by the CBC and the NFB. The filmmakers, Brian and Terence McKenna, used the Canadian surrender in the battle of Hong Kong, in December 1941; overwhelming losses suffered at Normandy during the battle of Verrières Ridge, in July 1944; and the end-of-war bombing campaign against German cities, which caused extensive civilian casualties, to depict Canada and its allies as incompetent and cruel. The utter neglect of national achievements — the Allies did win the war, after all — and the seemingly deliberate effort to paint Canadian veterans in the worst possible light ultimately led to an internal CBC inquiry on how the film could ever have been sanctioned as a documentary. In light of the investigation’s devastating report, the series was never broadcast again.

Defenders of Canada’s wartime contribution, who had objected so passionately to The Valour and the Horror, did themselves no favours the following year when a Legion hall in Surrey, British Columbia, refused to admit five Sikh veterans to its Remembrance Day ceremony, because they refused to remove their turbans. The branch had a rule that required people to set aside any head covering upon entering. Cook is much too kind in suggesting that the issue was “muddied, as are all these complex notions of heritage and traditions of an older age rubbing up against the modernity, diversity, and inclusivity of the current age.” The rule was shamefully racist and born of ignorance, and the outrage over its application was compounded by the fact that these Sikh veterans had risked their lives in fighting ideologies of racial supremacy. More subtle anti-Semitic sentiments, which emerged when Ottawa pledged to include a Holocaust gallery in a new exhibition space for the Canadian War Museum, further compromised the credibility — and respectability — of the veterans’ lobby.

It is difficult, and potentially misleading, to identify a single turning point in national attitudes, but the welcome that approximately 15,000 veterans received from 500,000 Dutch citizens when they returned to the Netherlands, in May 1995, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation of Holland, is as good as any. International recognition has often caused Canadians to rethink their history — even Lester Pearson’s contribution to the end of the Suez crisis was politically divisive before he won the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1957. After the Dutch reception, a reinvigorated national campaign helped establish the Juno Beach Centre, a museum dedicated to Canada’s role in the Second World War, in Normandy in 2003.

At home, the appointment of one of this country’s great military historians, the outspoken and controversial J. L. Granatstein, as director-general and chief executive officer of the Canadian War Museum marked a similar crossroads. The no-nonsense Granatstein spearheaded a successful effort to reinvigorate the aging museum alongside a number of other established historians, including Cook himself. A new building opened on budget and on time in 2005, and it has since drawn over half a million visitors every year. Apart from an early conflict with aggrieved veterans over the depiction of the Allied bombing campaign of German cities, the museum has been largely free of the partisan bickering that tainted previous memorial efforts. Canada still lacks a stand-alone Second World War memorial, but depictions of the war as “necessary” are far less divisive today than they used to be.

Cook concludes his captivating book with a call to action: “History is messy, tangled, and complex; it is unsettled and contradictory. It takes effort to understand, and its meaning changes from generation to generation. But we must push back against apathy and indifference. We must tell our stories, truthfully and bravely. For if we do not embrace our history, no one else will.” The words are compelling, but I’m not sure that they’re sufficient. In an era that has seen strongman dictators emerge on nearly every continent, when the norms of liberal democracy are regularly flouted and undermined, is it really enough to argue that the greatest threat to historical ignorance is a diminishment of the national self? I fear that we are past that.

In times of international strife, history is one of the most critical tools we have to remind us of the perils of ignorance. Sure, we must study the past to understand ourselves, but we must also think historically to better position ourselves to defend and preserve the broader liberal world order for which so many have sacrificed their lives and livelihoods. Whereas Cook remains enraged by the so‑called history wars — which witnessed the slow eradication of the teaching of Canadian constitutional, diplomatic, and military history at the end of the twentieth century — a number of us have moved on. We lost that battle years ago, and there is a larger war still to be fought. In twenty-first-century Canada, the fight for history is an existential one, and the forces of ignorance lined up against us are terrifying.

Adam Chapnick is the author of Canada First, Not Canada Alone: A History of Canadian Foreign Policy.