It’s a gaze that spans time and species. A sea wolf, the very definition of cunning and strength, stands on a rocky ledge with a huge rhododendron in riotous bloom close behind him. The photo on my desk occupies half a page in the Guardian Weekly and is arresting, all the more so because the face is familiar. With colouring and demeanour like that of a German shepherd (save for the short ears and straight hind limbs), the subject could be mistaken for a dog. Because it’s shot from a distance with a telephoto lens, the image dissolves the literal space between photographer and animal. The wolf appears close up — calm, curious, frozen — as two realms collide. In this intimate encounter between mammals — the watching and the watched — something suddenly shifts.

He was called Takaya, meaning “wolf” in the language of the Songhees Nation, whose territory lies in the southeastern region of Vancouver Island. The community knew him, as did a handful of others who encountered him on rare visits to Discovery Island, about a kilometre off the coast in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. First spotted there in 2012, he lived alone, surrounded by shoreline that afforded him access to harbour seal, salmon, and the occasional otter. He had adapted, abandoning the diet of black-tailed deer that has allowed coastal wolves to flourish ever since the old-growth forests were young. To flourish, but with intermissions.

Well into the 1960s, wolves were widely considered vermin and were hunted to near extinction in many parts of North America including Vancouver Island, where they were wiped out with the help of government-sponsored programs. Two decades later, though, they returned — swimming back across the Strait of Georgia to repopulate their island territories. The local population now numbers 250 (with 8,500 or so living throughout British Columbia).

It is unusual for a pack animal to live alone, as Takaya did for seven years — a long time in a wolf’s life. Perhaps it was age that prompted him to leave last January. Swimming across to Victoria, he followed a route downtown through backyards and laneways before he was stopped by a tranquilizer dart and removed to the coast near Port Renfrew. Authorities hoped he’d find the terrain there familiar, but by late March 2020 he’d made his way back across the interior to Shawnigan Lake, where he was shot dead.

Implicated in the extinction of others.

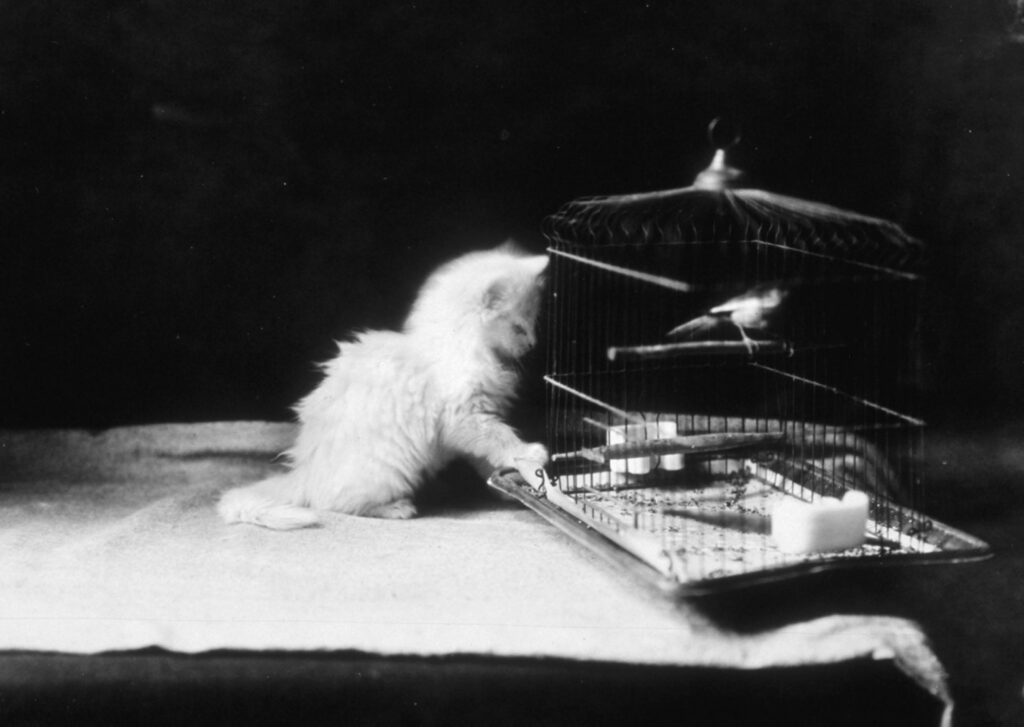

Jessie Tarbox Beals, c. 1903–28; Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America; Flickr

News of Takaya’s killing set off a debate that tended to vilify the hunter who fired the shot. Although it is not illegal to kill wolves, the deed seemed gratuitous, out of step with current ideas about the preservation of ecosystems and wildlife. Was he motivated by surprise, fear, opportunity? Was it trophy ambition? Truth is, most humans view other mammals with a certain myopia. While many of us criticize the hunting of wild animals — and their removal from natural habitats to live their lives in zoos and aquariums — we lavish decidedly unnatural lifestyles on our pets. What’s more, we fail to consider the impact that those animals we consider family have on those we consider wild. This is the subject of Peter Christie’s Unnatural Companions, a remarkable examination of our interactions with the pets we welcome in our homes. He shows how the simple act of adoption can have a dramatic impact on the world’s rainforests (which, in Brazil, are being razed so cattle can be herded for dog and cat food) and oceans (with schools of forage fish, like sardines, anchovies, and herring, being wiped out for similar purposes).

Christie, a science writer based in Kingston, Ontario, also reminds us how our pets have participated in the annihilation of entire species. One oft-quoted example is the Stephens Island wren, once found on a tiny isle just off the north coast of New Zealand’s South Island. A single cat, Tibbles, hunted it to extinction in a single year, 1895. We all know that since Tibbles’s exploits, many other species of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish have vanished. “We’re really in a massive extinction crisis,” Christie writes, quoting the Mexican ecologist Gerardo Ceballos. But what’s sobering is the critical role our pets play in that ongoing crisis.

The Guardian concluded that Takaya had only himself to blame: the wolf’s curiosity, explained Leyland Cecco, a Toronto-based journalist, was “built up from years of protection offered by the islands.” And that, he wrote, “was his undoing.” The apex predator had simply gone soft. Contrast this interpretation of animal curiosity with Christie’s take on our own: for tens of thousands of years, it was obligatory to pay attention to the world around us. “If you didn’t notice nature,” he points out, “you didn’t last long.” Far from making us soft, our inquisitive nature is hard-wired: “Our insistent need to know about the life around us has been so influential in our evolutionary history that our brains naturally veer in that direction — even as we try to technologically distance ourselves from it.” It has also had lethal effects on the animals, plants, and untrammelled landscapes that “are fuel for our powers of metaphor and myth, connection, and understanding.”

We see this in the stories we tell our young, stories like Edward Lear’s nonsense poem “The Owl and the Pussy-Cat” and Dennis Lee’s inimitable “Alligator Pie.” Yet what we retain from such tales wilts in the face of the great extinction we are living through now — only the sixth in the billions of years of life on earth. Sometime after 1850, the mass of humanity “eclipsed that of all the wild land mammals on earth,” Christie observes, and since 1900 nearly half of all mammal species have seen their ranges reduced by more than 80 percent. Our built-in need to connect with other animals has not gone away, however, so we increasingly turn to domesticated species: the cats, dogs, birds, fish, and reptiles whose birthdays we celebrate and deaths we mourn. Around the world, humans keep an estimated 113 mammals as pets, along with 585 species of birds and 485 species of reptiles. Many of the most popular animals — like parrots — are also the most endangered. The reptiles we keep, for example, “are five times more likely to be threatened with extinction” than those we don’t. The multi-billion-dollar pet industrial complex, Christie reminds us, contributes to an increasingly negative feedback loop.

At last count, 41 percent of Canadian households have at least one dog and 37 percent have at least one cat, figures that have surely gone up during the pandemic. Collectively, we own over thirteen million of them — four-legged companions who always seem to be hungry. (Another ten million dogs and cats are on the streets.) Christie reminds us that, unlike the chickens our grandparents might have kept as backyard sources of protein, our best friends “are nothing but protein consumers.” He cites Gregory Okin, a geographer at UCLA, who has done the calculations: “Dogs and cats — if they were their own country — are about the fifth largest global meat consumers.” That puts them just behind Russia, Brazil, the United States, and China.

Tibbles may have wiped out a single species, but her feline descendants are implicated in the extinction of at least 175 others. In Australia, for example, feral cats have joined red foxes (also introduced from Europe) in the decimation of 10 percent of the continent’s 273 autochthonous land mammals. Another fifth of those species are now considered threatened. In short, our dogs and cats have become roaming invasive species, whether we let them out of the house for a few hours or they spend their days on the couch. It’s increasingly difficult to escape the paradox: our stand-ins for nature are helping us destroy the very thing we desire.

For a number of years, I lived on Gabriola Island, one of the larger Gulf Islands located up the coast near Nanaimo. On ten acres of raw land, we built a one-room cabin, heated by a wood stove and set in a small clearing, ringed by cedar, Douglas fir, and arbutus. We were the only human residents on that part of Ferne Road, with panoramic views of Mudge Island and the Strait of Georgia, the Coast Mountains rising in the blue distance. Being in a rainforest, those acres were alive with sounds and smells and growing things: fungi and nurse logs, stinging nettle and alder saplings supple enough to bend into tent frames, tree frogs harmonizing by a nearby spring. The fir trees along the cliff would sway with the prevailing winds, like a chorus line mocking the stolid maples and their leaves the size of placemats. In early evening, the meadow would succumb to the hermit thrushes, their calls beginning tentatively, a riff of ascending notes, sharp as a pennywhistle and mysterious as mercury. The air would crackle with the expanding sound as one call became three and then six in a surrounding circle.

As Takaya would learn years later, islands are an easy reach for creatures that fly and those that swim — wolves and cougars, otters and beaver, all of them known if not often seen around Gabriola. Domestic cats, however, don’t swim. Unlike the wounded band-tailed pigeon that took refuge in the alder sapling by the cabin one spring, scrappy toms can’t get to Gabriola on their own. But one day, a stray emerged from the woods accompanied by a female about to have kittens. When she and her five newborns left us — for the vet and then for homes around the island — he lingered. We didn’t feed him at first, but we did leave the window ajar so he could visit. Sometimes we would disappear for a time, always to find him still around when we returned. He seemed at ease with the arrangement, and the feeling was mutual.

This black and white tuxedo cat, a deft hunter and patient confidant, came armed with a sense of humour. In the lamplight shadows, we would watch him with an intensity we rarely gave the darkened forest itself. Once, for his amusement, I pretended to swallow a dead mouse. He fell for the trick and, a few evenings later, returned with two mice stuffed in his jaws — one for me and one for him. When he first arrived, we were rereading Paradise Lost, enjoying Milton’s tart humour and noting how Lucifer delivered insights as well as bons mots about the superiority of Hell. The fallen angel’s name seemed to suit our earthly trickster, who even then struck me as too clever by half. And who, I now have to admit, was an environmental disaster.

Back then, I loved that Lucifer lived au naturel, without our having to supply commercial cat food. But there’s no getting around the fact that he was a killing machine — small mammals, reptiles, insects — with an ecological footprint much, much larger than his little paws would suggest.

When we moved east, we brought Lucifer to live in Toronto, to a two-storey semi that backed onto a park in South Riverdale. He remained an outdoor cat who came inside as it suited him, and he found new hunting grounds upon his arrival. But he also grew fond of kibble and, eventually, tinned seafood, even though mousers aren’t natural fishers. (Try telling that to Australian cats, who, Christie notes, average thirty pounds’ worth of seafood each year.)

Though he had access to that park, Lucifer didn’t thrive in Toronto. Like Takaya, he died before he grew old.

When we tell the story of people and their pets, we often miss the true ending and, quite frankly, the true beginning. We think we know where to get pets — the breeders, the pound, the various rescue organizations — but few of us see the way the global supply chain actually operates. When we factor in all of them — the snakes, the gerbils, and, yes, the dogs and cats — we have 82 million animals sharing Canadian homes. That’s more than twice our human population. And each year, six to eight million of them end up in shelters.

People and domestic animals have an ancient connection based on mutual benefit and companionship. The association was originally defined by work, which dogs could often be trained to do. The job of cats — containing the rat population in granaries — was self-assigned, the work being its own reward (as Lucifer liked to remind me). But despite this primeval connection, we know that to experience nature requires something more than visiting the local dog park or roughing it on the Gulf Islands with a humorous stray. To actually hear the planet talking, as it warns us of what’s to come, we need to reframe how we see animals — animals like Takaya and Lucifer both. “Pet ownership and a love of wildlife are both less like a hobby and more like a state of mind,” Christie writes. “It’s an emotional and psychological belief system.” Adoring pets and admiring wildlife are not mutually exclusive, he reminds us, but we need to reconfigure those acts in ways we may have forgotten.

Personally, I always configured my relationship with Lucifer as an off-grid and non-commercial one. We had a pact, he and I, more than he had an owner or I had a pet. Unnatural Companions shows how even that arrangement was magical thinking at best.

Beside me at my desk is another photo — with another gaze that spans time and species. Familiar slanted eyes of yesterday stare through the camera into the present. They look beyond me and into a garden that hosts the mischief of rats who recently evicted a scurry of chipmunks, who nonetheless continue to raid the bird feeder while dodging incoming cardinals, chickadees, and sparrows. They watch as a lone sharp-shinned hawk, the neighbourhood’s current apex predator, lands high in the naked branches of a Norway maple.

I’ve looked into Lucifer’s eyes often since those days on Gabriola Island. Now I have to wonder: Are we finally seeing each other differently?

Susan Crean is the author of several books, including The Laughing One: A Journey to Emily Carr and Finding Mr. Wong.