In September 1993, I taped the front page of the Jerusalem Post to my dorm room wall. The cover photograph is indelibly inked on the memories of so many. The Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, with his thick glasses and dark suit, stands on one side, while the Palestinian Liberation Organization chairman Yasser Arafat, in keffiyeh and khaki military jacket, stands on the other. U.S. president Bill Clinton is positioned between them, his arms outstretched like a benevolent god. The former antagonists lock hands —

a gesture, along with the agreements behind it, that would win them the Nobel Peace Prize.

As I look back to that time, when I was studying at Hebrew University, I can see the picture there above my bed. But is it true, as I dimly remember, that I put question marks around it? Why would I have done that? Was it my learned distrust of a man who I had been told my whole life was a terrorist? My father had escaped persecution in Egypt in the late 1940s and had come of age in Israel (he would later fight against his birth country in the Suez Crisis). Arafat and the PLO had publicly recognized the state’s right to exist only five years before he and Rabin signed the Oslo Accords. Did I know how few details of the peace process had been hammered out? That it was destined for failure? Or was I just being cutesy somehow? I check my diary for answers, but all I find are descriptions of hookups with random boys, complaints about bitchy girls, and plans for a trip to Greece. I was nineteen, after all, and it was my first time living away from home. This was a major historic moment, but, in an equally pressing way, so was my kiss on the dance floor of the Orient Express, a club near campus, the previous Wednesday. (For the record, the man I kissed didn’t turn out to be my future husband; he showed up later in the year.)

A tug-of-war between heart and mind.

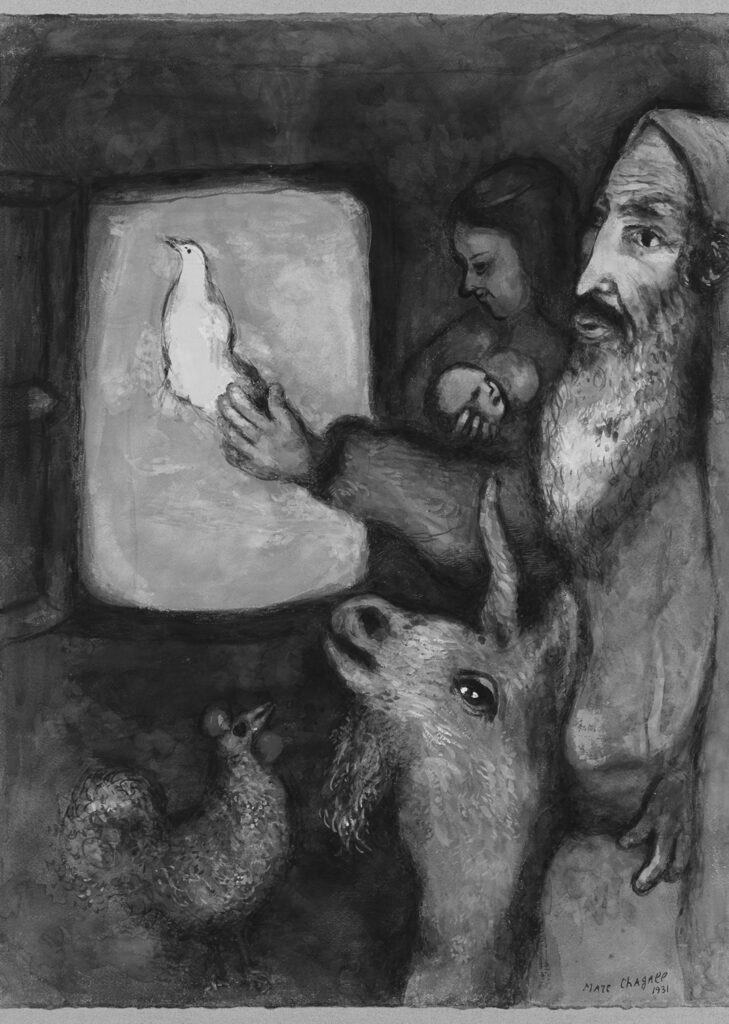

Marc Chagall, 1931; RMN-Grand Palais; Art Resource, New York

Reading Mira Sucharov’s deeply self-reflective Borders and Belonging makes me reach into the annals of my own memory, in part because so much of my story resembles hers. It’s true that she grew up in Winnipeg and later Vancouver, and I grew up in Toronto. Yet she speaks to and for a generation of Canadian Jews who were raised to see one country as their home and another as their homeland. Like Sucharov, I attended a Jewish day school, where I learned Hebrew and Israeli literature alongside the Torah and the Talmud. I spent summers at a sleep-away camp, where the campers wore gumis (friendship bracelets) and cool counsellors, back from Israel trips, sported asimons (phone tokens) on silver chains around their necks. I unhesitatingly chose Jerusalem for my study year abroad, and I travelled, albeit nervously, to Egypt during term break, where, with my Canadian flag sewn on my backpack, shouts of “Canada? Canada Dry! Canada Dry!” accompanied me everywhere I went. Finally, like Sucharov, as I got older and met people outside of my bubble — Arabs, Muslims, and the left-leaners who fill the halls of academia — I became uneasy with some of the Zionist myths I had learned as a child.

No, the land in Palestine was not all fairly purchased at the turn of the twentieth century. It was not a patchwork of barren desert and swampland, “a land without people for a people without a land,” as my schoolteachers had told me. No, the original impetus for the Zionist enterprise cannot be so easily disentangled from European imperialism, and the socialist and democratic promises of the early state have not been upheld. Yet, well versed as I am in the millennia of persecution of Jews, as well as my own family’s decimation in the Holocaust and their expulsion from Arab lands, I find my eyes watering — still — at the longing in the Israeli national anthem, “Hatikva”: “Our hope is not yet lost, / The hope that is two thousand years old, / To be a free nation in our land, / The Land of Zion, Jerusalem.”

I take my children to Israel to teach them about our history, about their connection to the country. “Here is where Saba grew up,” I tell them of their grandfather. And “here is where the Beit Hamikdash, the holy temple where ancient Jews worshipped, stood.” But I also talk to them about the Nakba. I highlight loss where I was taught to see only gain.

Although I didn’t know Sucharov growing up, our paths were destined to cross. I met her in December 2017 at an Association for Jewish Studies conference in Washington. We both work in the field, though she is a political scientist and my research is in literature. We met again at a conference in England and then in Boston — so goes the academic circuit. We kept in touch, and I once visited Sucharov on a family trip to Ottawa, where she teaches at Carleton. Mostly we communicate through Facebook.

Sucharov is very invested in social media. She wrote Public Influence: A Guide to Op‑Ed Writing and Social Media Engagement, in 2019. So it’s no surprise that some of the key moments she describes in her memoir took place online. Like her thousands of other Facebook friends and followers, I watched in real time, only months after that book was published, as she argued with “friends” who had played a role in cancelling her talk at a panel on Israel and Palestine at York University, my alma mater. Her chief antagonist in the debate is emblematic of many of Sucharov’s acquaintances — parents of her children’s playmates, people she went to camp with, family friends — who have been alienated by her politics. The public nature of the forum exacerbated the argument; there were ad hominem attacks, ethically questionable screenshots, and pile‑ons. The issue at hand was Sucharov’s alleged support of BDS, the movement that calls for people to boycott, divest from, and sanction Israel and Israelis.

But the story is complicated, and here’s where the memoir is at its most interesting — and maddening. At no point does Sucharov declare herself pro‑BDS. Instead, she prevaricates, as she did in a 2018 opinion piece for the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, where she wrote, “BDS activists may actually be on to something.” Or maybe not? When the director of York’s Centre for Jewish Studies tried to save the event in the face of protests, he said, “Some community members have fixated on the supposed support for BDS on the part of one panelist, in spite of her having written in the Canadian Jewish News that ‘I have gone on record many times opposing the end game of BDS.’” He noted, “All three of our panelists are pro-Israel.”

This attempt to smooth things over irritated Sucharov. Why did she have to be anti-BDS and pro-Israel to speak? Why did anything but her scholarly expertise matter? The CJN itself put a similar spin on its coverage by assuring readers that Sucharov was opposed to the movement. When she posted the CJN article to her Facebook page, a colleague commented, “I didn’t know you went on record as opposing BDS.” Rather than confirming or refuting the claim, Sucharov replied, “Across hundreds of op‑eds over the last decade my views about BDS (whether as tactic or as a set of political goals) have evolved.” Did that mean she now supported it? Toward the end of the memoir, she admits, “I’ve been deliberately oblique about my position.”

The achronological nature of Borders and Belonging allows Sucharov to perform for the reader her different, even conflicting relationships to the state. She offers stories that demonstrate the leftward shift of her politics, but this move falls short of an emotional divestment. (How short remains up for interpretation.) Maybe it’s because she notes several times that she speaks to her children in Hebrew; maybe it’s the nostalgic tone she strikes when she writes about celebrating Yom Ha’atzmaut (Israeli Independence Day) as a child. Maybe I have trouble believing that she has disavowed her affiliation with Israel because I wouldn’t believe it of myself. Or because I have witnessed in academia, close up, how aligning yourself with even mildly unpopular politics — and Zionism is very unpopular — puts you at risk of full-scale ostracism.

What Sucharov demonstrates is a tug-of-war between heart and mind, between love for Israel and criticism of it. Or love of the people who love Israel, and a wary attempt at setting up camp amid those who do not. She relates a conversation with her grandmother, who might be seen as a stand‑in for Canadian Jews, one of the largest and most Zionist communities in the world. “Israel is like my child,” Sucharov’s baba explained. “It’s hard for me to hear it being criticized.” And in part for her baba, for all the babas, Sucharov tempers her growing condemnation of the country, refusing to be an advocate for or opponent of the concerted fight against the homeland.

In universities, we teach students to delve into the complexity of the world, to learn how to hold contradictory ideas in their minds. Still, for many, a person without a position is worse than a person with an opposing one. You’re with us or against us. Stand for something or you’ll fall for anything. Look at Twitter: people will fight to the death for the claim that pineapple doesn’t belong on pizza. In-betweenness, uncertainty, and doubt are not acceptable stances. Deeply religious Pi Patel in Life of Pi declares atheists his “brothers and sisters of a different faith.” He says, “Every word they speak speaks of faith. Like me, they go as far as the legs of reason will carry them — and then they leap.” For Pi, the problem lies not with those who perch on the other side of the chasm but with those who sit inside it: “To choose doubt as a philosophy of life is akin to choosing immobility as a means of transportation.”

Many readers will want Sucharov to take a stand. They will want her to provide irrefutable evidence, as a scholar ought to do. But at the end of the day, this is a memoir, and Sucharov is honest about her changes of heart. She recalls when she read the philosopher Max Nordau as an undergraduate and waxed poetic about his concept of the “muscle Jew”— about working the land, growing potatoes, living on a kibbutz. A guy she liked at the time responded, “Jewry of Muscle? That sounds positively fascist!” The Sucharov of today looks back on the Sucharov of a quarter century ago and considers the way the romantic, nationalist narrative she had fostered could disappear in a moment, in a word. Refusing to grant her younger self any mercy, she reveals that she had wanted the young man’s approval. In another anecdote, she recounts being moved when a boy she went around with gave her a copy of Edward Said’s Orientalism at the end of her year abroad in Jerusalem. Even in adulthood, she feels compelled to drop her affiliation with a group that had seemed to her even-handed — as it sought “to fight against the occupation and fight against academic boycotts”— after her “work husband” told her that opposition to BDS made her “the enemy.”

It’s true that ideological positions are not developed in a vacuum; they happen alongside and through everything else. Nevertheless, these moments are hard to read. What I want to read is Sucharov reacting to an act of injustice, a racist law passed, houses bulldozed. These, my rational, feminist self tells me, are reasons to change one’s political stance — not some small comment that upends beliefs developed by a thoughtful, educated woman over a lifetime.

But of course that’s not fair. Politics is emotional as well as intellectual — for Jews, for Palestinians, for everyone. Notions of “home” and “homeland” are more than passports or flags sewn onto backpacks. People touch our lives in all sorts of ways. Some give us books. Some reveal our blind spots. We listen to those we care about. They make us who we are.

In one of the memoir’s final scenes, Sucharov describes a time when she broke down in front of her students at Carleton and fled the room in tears. The topic that threw her was not Israel but rather another childhood idol smashed. She had been speaking about The Cosby Show, how much she (a child of divorce) had admired the family values, and how shocked she had been to learn the truth about Bill Cosby. How could she reconcile something so beautiful and something so ugly, inextricably bound together? After the seminar, a student she had taught the previous term followed her out. Sucharov was embarrassed for her weird behaviour. “It’s not weird at all,” he told her. “It’s human.”

Karen E. H. Skinazi is a senior lecturer and director of liberal arts at the University of Bristol.