The Canadian War Museum’s Canvas of War, which toured the country throughout 2000–01, was the largest exhibition of Canadian war art ever organized. It featured the work of some of our best artists, including members of the celebrated Group of Seven, who had witnessed the slaughter of the thousands of young men who had fought in two world wars. The painter Frederick Varley, for example, had seen the undeterred heroism, immense sacrifice, and unimaginable losses of the “war to end all wars” at first hand. “We are forever tainted with its abortiveness and its cruel drama,” he said of the front, “and for the life of me I don’t know how that can help progression. It is foul and smelly — and heartbreaking.”

An important book accompanied Canvas of War. While it featured only a small portion of the 13,000 paintings, drawings, and sculptures held in the museum’s vaults, it was nevertheless a very fine collection of desperately sad art, as well as formal portraits of some pugnacious-looking military leaders.

Neither the exhibition nor the book included the battlefield paintings of Mary Riter Hamilton. Yet she was there, shortly after the First World War ended, and, unlike most of her contemporaries, she painted the sites where bodies and body parts were still being dug out of the mud. She was at the ruins of Ypres, in West Flanders, and at Vimy Ridge, in northern France, where 3,598 Canadians had lost their lives and more than 7,000 were wounded. (In total, the war claimed 61,000 Canadian lives and wounded another 172,000.)

Many of the artists sent to Europe to commemorate Canada’s role in the Great War were backed by the newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook, through his Canadian War Memorials Fund. Established in 1916, it was responsible for more than 900 works. But it did not fund Mary Riter Hamilton as she toiled to capture hundreds of scenes. Nor did the Advisory Arts Council for the National Gallery.

She captured the spirit of resilience.

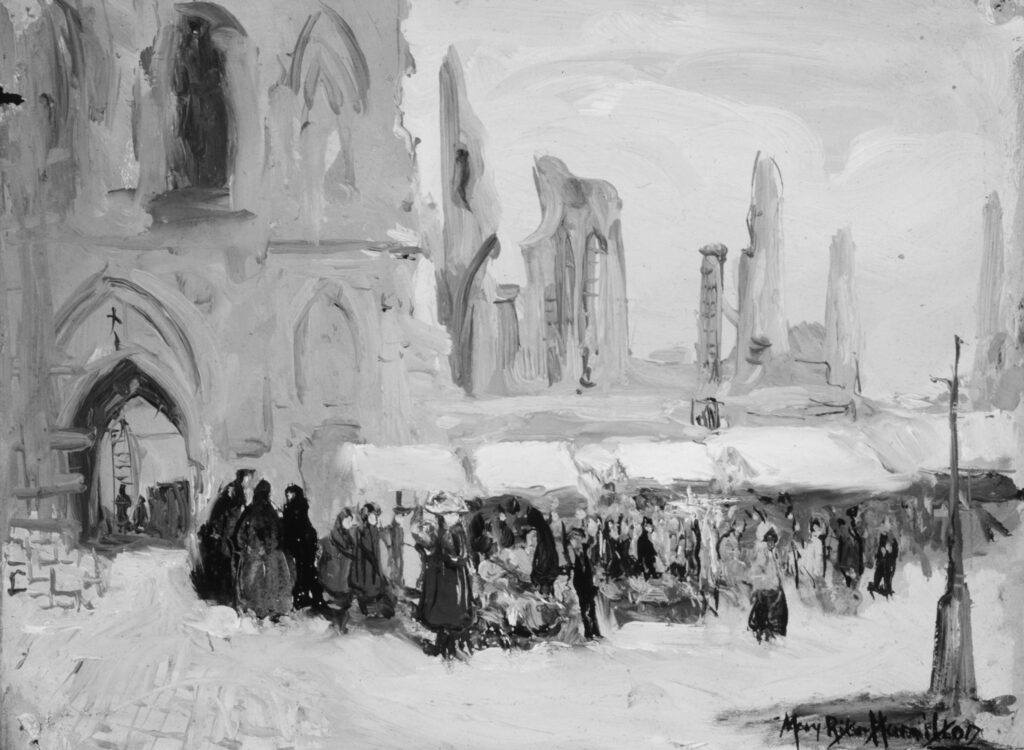

Mary Riter Hamilton, Cloth Hall, Ypres—Market Day, 1920; Library and Archives Canada

It is clear from Irene Gammel’s meticulous research that Hamilton’s exclusion was not for lack of effort on her part. It is almost painful to read her tireless pleadings and the dismissive responses. Although Robert Borden had purchased some of her pieces shortly after he became prime minister, although Government House in Victoria had commissioned her to do the portraits of fifteen lieutenant-governors, and although she had exhibited her paintings abroad, the granting agencies of the day were not interested.

Perhaps the reason was Hamilton’s forthright manner in personally approaching members of the Advisory Arts Council. Perhaps it was her being a westerner or being too aggressive for a lady or her “defiance of institutional power,” when she insisted that the West should be represented in the National Gallery. Regardless, the Ottawa establishment did not bend. It viewed her as “a troublesome woman, no matter how good her art.”

During the war, Canada commissioned no women artists to travel overseas, but Gammel’s I Can Only Paint makes it clear that even if women had been sent, Hamilton would not have been among them. It was a question not of talent but of “temperament.” She was a painter who showed too little humility.

It was not until 1919 that Mary Riter Hamilton, a widow, finally made it overseas with the support of those she wanted to honour, through the Amputation Club of British Columbia and The Gold Stripe, a magazine for wounded veterans. She would send paintings to her editor, and all profits from their sale would go to the soldiers. The University Women’s Club in Victoria also offered a little funding, as did Margaret Janet Hart, who, though not personally wealthy, managed to send some money when Hamilton needed it the most.

Hamilton sold several paintings and left instructions with Hart to sell whatever art, jewellery, and property she had left, then got ready to leave — travelling from Victoria to Vancouver and onward to New York via Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal. Contrary to the claims she made in her travel documents, she was not thirty-five but fifty-one. Had she revealed the truth, she worried, she might not have been able to board the SS La Touraine, bound for Europe.

Upon her arrival in France, she witnessed the destroyed city of Arras and the remnants of Vimy, littered with spent shells, shrapnel, wrecked tanks, unexploded ordnance, muddy trenches, and shreds of clothing. Her paintings — of Arras, of Villers-au-Bois, of soldiers searching for bodies, of Vimy Ridge in its desolate landscape — are stark, melancholy, bereft.

Hamilton captured the aftermath of a battle where young men — some of them barely sixteen years old — had clambered up sodden slopes, and you can feel her own sense of loss as you study the art. The colour reproductions of Isolated Grave and Camouflage, Vimy Ridge and of her Mont-Saint-Éloi paintings are among the finest in the book. Other works are sunny in a way that Hamilton’s lonely, isolated time in Europe was not. The weather was cold and wet, her small hut was leaky, and she was always running out of food and money to replenish her supplies.

The extraordinary Tragedy of War in Dear Old Battered France depicts the remnants of a tall wooden cross and parts of its sculpted Christ figure, in the Sainte-Catherine graveyard where thirty-one Canadians had been buried. Hamilton’s title speaks of her strong feelings for France, where she had studied before the war. Her devastating paintings of Flanders destroyed, of a Canadian monument at Passchendaele, of a dugout along the Somme, and of the cemeteries and burnt-out landscapes — they all depict her horror at what the soldiers must have suffered.

Her sympathy for the men who had endured the war extended to the prisoners who continued to languish in makeshift camps. With disease rampant and facilities scarce, the young German boys who appear in some of Hamilton’s paintings seem as lost and broken as many of the damaged Canadians who had recently returned home.

Because she was there after Armistice Day, Hamilton was able to show how life began to return in France. The First Pilgrimage to Notre Dame de Lorette after the War of 1914–1918, one of the larger reproductions in the book, shows a throng of women and children marching to the remains of a church in Ablain-Saint-Nazaire. The sky is heavy, the scene dark with small patches of sunlight on the ruined towers and on the new sprouting grass. Many in the painting hold umbrellas to protect themselves from a downpour that threatens to drench the procession.

Some of Hamilton’s most arresting work springs from her observations of life returning even to the front lines. Trenches on the Somme is filled with startlingly red poppies against a grim purple sky, for instance. Two older men in white put their shovels to work in Filling the Shell Holes in No Man’s Land, with a few charred trees in the background.

In May 1920, Hamilton arrived in Ypres, which she found largely destroyed, its cathedral just a few columns and Gothic arches, its famous Cloth Hall roofless and full of debris. Yet the main square was coming alive with a flag-waving celebration, and busy stalls offered colourful clothes. The Market among the Ruins of Ypres captures the spirit of a resilient city that had seen much of the war’s action. One of Hamilton’s paintings of it was exhibited at the Salon in Paris in 1922.

After six years of documenting the end result of war, Mary Riter Hamilton managed to scrape together enough money to return home. She left Europe “a wounded war worker but also an unsung hero who now needed help herself,” Gammel writes. With her collection completed, Hamilton hoped that the National Gallery would see its value and purchase it. But the museum declined in April 1926, on the grounds that her paintings “duplicated work already in the Beaverbrook Collection of War Art.”

Although a number of Canadian artists had tackled similar subjects in Europe, Hamilton’s approach was entirely different. As a small, rather perfunctory gesture, the gallery’s director, Eric Brown, offered to buy three of her oils. But Hamilton — ever the “troublesome woman”— rejected the offer and accepted, instead, one from the Public Archives of Canada to house all 227 works.

Irene Gammel, a professor of literature and visual culture at Ryerson University, has authored numerous books, including Looking for Anne of Green Gables, from 2008. With I Can Only Paint, she has given us a revelation about a remarkable painter.

Anna Porter is the author of Deceptions, an art-world thriller.

Related Letters and Responses

Joel Henderson Gatineau, Quebec