Although it seems a good while since Canadians looked upon China benignly, it’s actually not been that long. Until fairly recently, there seemed to be something of a consensus in government, business, and academic circles that Communist Party leaders had miraculously presided over the fate of a billion-plus people by fostering a workable social cohesion and diligently pursuing the admirable work, initiated by Mao Zedong, of relieving historic poverty. Under the post-Mao leadership, the thinking went, that diligence had progressively become almost messianic.

True enough, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution was a nasty bit of business, but it was obviously part of some growing pains and was really interesting as a social experiment. On top of all that, the consensus view went, the West had sins of both commission and omission to atone for in its years of colonial expansion, international dominance, and, as we are never allowed to forget, pure racism.

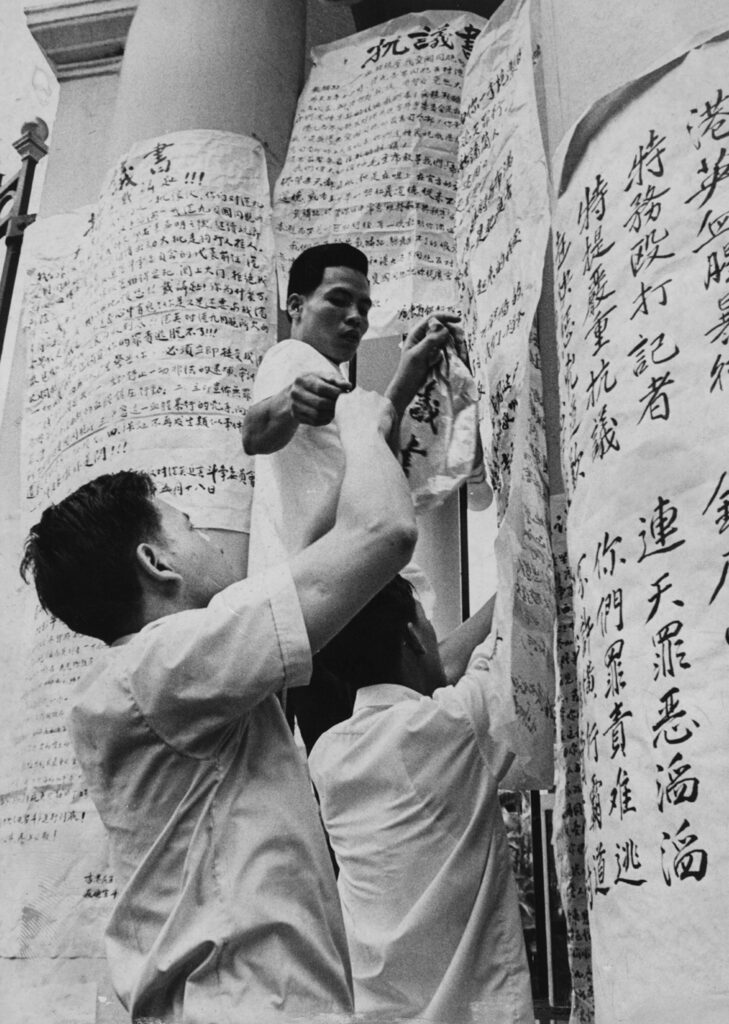

We went to see a poster protest.

Central Press; Stringer

Canadians, in particular, could look upon the first fifty years of Communist China, from 1949 to the takeover of Hong Kong in 1997, less censoriously than our American neighbours, who were prejudiced by Washington’s stubborn support of Taiwan (and the remnants of the horrible Kuomintang regime under the failed leadership of Chiang Kai‑shek). Our support for the newer China even had a secular saint in the form of Norman Bethune, who helped to buttress a “unique” relationship. No longer.

Today Canada and the rest of the world face a hostile and militant tiger of a country under the increasingly chauvinistic leadership of Xi Jinping, who is clearly intent on transforming China into not just a world power but a power to equal and eventually outpace the United States. This transformation manages to meld some of the most degrading aspects of Western capitalistic practices with a dark, bottomless pool of vicious totalitarian might. And it does so with confidence.

For many on the outside, China now looks impervious to any possible course correction as it engages in a new Long March, toward global economic supremacy. But enter Roger Garside, who seems to have thrown all caution to the winds with an explosive new book. In China Coup, Garside imagines internal machinations leading soon to the replacement of Xi, the state’s bullying ruler, by those who are convinced that China must take a different and more democratic route forward if its dramatic economic gains are to survive. That’s also what it must do to avoid a potentially calamitous confrontation with the United States and the increasingly alarmed Western community of nations.

Immediately after the Cultural Revolution, a great many sinophiles and journalistic old China hands swallowed Maoist thinking holus-bolus, and some of it continues to animate the conversations of intellectuals and political strategists (all devastatingly served up in Julia Lovell’s comprehensive Maoism: A Global History, which won the 2019 Cundill Prize). But in 1980, Garside published a most prescient book, Coming Alive! China after Mao, which stripped away the deadly dogma and helped explode a dangerous mythology.

Garside was one of the first to predict China’s extraordinary economic expansion. He was also one of the first to warn against an unholy alliance of unfettered capitalism and totalitarian Communism. He had a kind of detached intelligence that could see immediately through surface static and nonsense, coupled with an imagination that allowed him to get ahead of the game and correctly foresee future events or trends. Tied to his own deeply humanistic values, this was a powerful tool for analysis, even if it sometimes left him vociferously angry at Western self-deception. More often, however, it led him to astonishing insights.

I first met Roger Garside at Christmastime, in 1977, when he was first secretary at the British Embassy in Peking (soon to be re-anglicized as Beijing). I had just arrived to take up residence as the Globe and Mail ’s eighth Peking correspondent, and there was Roger dressed as the Widow Twankey at the embassy’s annual pantomime for all the diplomatic children. (The humour, of course, was mostly designed to go over the heads of the little ones, but it hit home in the more prurient recesses of their parents’ consciousness.) In costume, Roger was somewhere between Dame Edna and Mort Sahl. He was just as intriguing out of it, and we quickly became good friends and allies in the everyday necessity of figuring out the regime we were both employed to decipher.

In those days, you couldn’t survive as a Western journalist in China without allies — and not just any allies, but those who would respect relationships. You certainly couldn’t mix and match diplomats and journalists willy-nilly. Play a double game once, and you were out of the bigger game altogether. Finito.

My diplomatic allies were Roger and Donald Keyser, a young sardonic and brilliant American, who three decades later was arrested and imprisoned for spying on behalf of Taiwan (presumably angry at his own government’s “betrayal” of an emerging democratic island). My fellow hacks included the two outstanding journalists at Agence France-Presse, Georges Biannic and Francis Deron, as well as the legendary Nigel Wade, a correspondent for the London Daily Telegraph and the first to report on the fall of the “Gang of Four” (Mao’s widow, Jiang Qing, among them). These were dramatically eventful days as China shed the worst oppression of the Cultural Revolution, and it was possible for the first time in two generations to imagine a country free of the strictures that made everyone look like automatons, much as North Koreans can still appear in their abidingly wretched regime.

Roger was especially perceptive, thanks to a previous posting as a junior diplomat when the revolution was at its hottest. The Reuters correspondent, Anthony Grey, had been under house arrest, and the British embassy was constantly under siege by Red Guard protesters, who were irritated with the colonial administration’s treatment of Communist journalists in Hong Kong. Roger was the diplomat who went to Grey’s house the day he was finally released. From all this, he had developed a very clear vision of the regime’s cruelty, as well as an equally clear idea of how Chinese people managed to survive as they waited for better times.

He also seemed to understand how the local leadership operated internally. With this expertise, he came to my rescue once and left me indebted to him. In fall 1978, while embracing my interior gadfly, I took a visiting American journalist, Robert Novak, to the Xidan democracy wall, to show him how a poster protest worked. In those comparatively halcyon days, when regime change was in the air and the police would not act until it was apparent how the leadership struggles would end, there was a giddy sense of freedom. A young Chinese asked Novak and me, in English, what we thought of the big-character posters, and I blurted out that my guest was interviewing the vice-premier, Deng Xiaoping, the very next day. Perhaps, I wondered aloud, it might be useful for him to hear some questions from average citizens, which he might ask China’s paramount leader if he had the chance.

It took me a minute or two to realize the dangerous territory I had entered: I had made an offer to a group of ordinary Chinese citizens, one they had never dreamed of having. Within a matter of seconds, we were surrounded by a vast throng of mostly young men, who believed they now had the means to express their views to their own leadership, courtesy of two foreign yokels. People wrote out questions and forced them into our hands, and then demanded to find out how they would know the answers. Still in a kind of la‑la land, I said I would return at the same hour the next day and “report to the masses.” As soon as the words came out of my mouth, I wanted to take them back.

I dropped Novak back at his hotel, and by the time I returned to the Globe bureau, the phone had been ringing for over half an hour. My colleagues and some diplomats were warning me that I would be expelled before the next day was over for interfering in China’s domestic affairs. In the midst of this hullabaloo, I reached out to Roger. “Oh, they are such idiots,” he said, referring to my many Cassandras. “If the regime doesn’t want to encourage what’s going on, they will cancel the interview and you will have nothing to report. If they want to send messages to the masses, they will have already prepared answers for Novak, which will be duly got to you and, dear John, you will be doing the regime a favour. Congratulations. You may soon be on the Party payroll. Either way you are safe.”

Indeed, that is what happened (well, not the payroll part). This showed me, if I didn’t know it already, that Roger was more than the coolest diplomat in town. He was also the wisest about the regime. For a while, Roger had made the same evaluation that all the bien pensants — myself included — were making in those days: that by embracing the free world and experimenting with free enterprise, China would inevitably bestow further freedoms upon its people, for whom he had inordinate affection and admiration. But he grew increasingly impatient with his own Foreign Office’s slowness in understanding what was happening in post-Mao China and in grasping all the opportunities for the West to reach out and assist the country in taming its totalitarian instincts.

After he left the foreign service, Roger Garside led a pretty interesting business life, in and out of foreign trade and international deal making, but he never took his sights off China. He had realized that a one-party state that demands of its people total loyalty and subservience would not give up its dominant role, and so the hopes of the free world, like the hopes of liberals within China, would soon be gutted.

But what if, he wonders in the opening of China Coup, an internal revolt could change China’s course? Garside, who once warned me never to write anything about China that didn’t have a back door to escape through, spells out this scenario for those who can’t even imagine the changes that could come. This upheaval, even if it doesn’t happen exactly the way he describes it, is surely bound to happen, and within most of our lifetimes (even counting the old duffers like myself).

Garside’s most crucial observation is about the degree to which China has enmeshed itself in global money markets. Its position certainly allows the country to threaten Western interests, especially when it is of a mind to bully us. But, as he points out, China has also opened itself up to the kind of foreign manipulation that always irked Chairman Mao. The West, ironically, is in a position to effect regime change of a sort: “It would surely play badly for Xi if the Chinese elites were . . . left substantially poorer and shackled within the nation’s financial system.”

China Coup opens and closes with this scenario, which Garside backs up with documentary evidence and deft insight. It is both a compelling read and a convincing one. At the very least, if Canadians are worried about growing Chinese Communist influence in the free world, they can find in this book a key to unlock a twenty-first-century riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.

John Fraser is the executive chair of the National NewsMedia Council of Canada.