I should probably dislike Erin Dej’s A Complex Exile: Homelessness and Social Exclusion in Canada more than I do. After all, the book is a searing critique of modern homeless shelters and their sometimes paternalistic and exclusionary practices. I happen to run one of those shelters in Montreal, the Old Brewery Mission.

Like other shelters across the country, the Old Brewery has changed dramatically over the past twenty years. It is difficult today to find a shelter in Canada that is simply a witness to the misery and pain of its residents, as such places were in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Almost without exception, through casework and psychosocial intervention, we actively help the people we serve to turn the page and exit the brutal life of homelessness.

Earlier this year, Deirdre Freiheit, president and CEO of Shepherds of Good Hope, summarized the prevailing orthodoxy in an Ottawa Citizen op‑ed. Our organizations “don’t create homelessness,” she wrote. “We are trying to reduce it, by meeting people where they are without judgment and moving them into permanent homes.” Community Solutions, a leading umbrella group in the United States, describes its goal as a “future that ensures homelessness is a rare and brief experience, and never an enduring or recurring way of life.”

Admittedly, shelters don’t always succeed in this mission. I was the director of the Old Brewery from 2004 to 2008, and I began my second tour of duty in 2020. When I returned to the job, I was surprised to see Norman again. Now in his mid-fifties and still struggling with drug addiction, he had managed to get an apartment and a job for a short while but eventually lost both. When we said hello to each other last year, he told me that he’d be back only for a little bit. Although over 80 percent of individuals who experience homelessness do so in a temporary or episodic way, 20 percent are homeless chronically, meaning for more than six months at a time. In Norman’s case, it’s been closer to fifteen years.

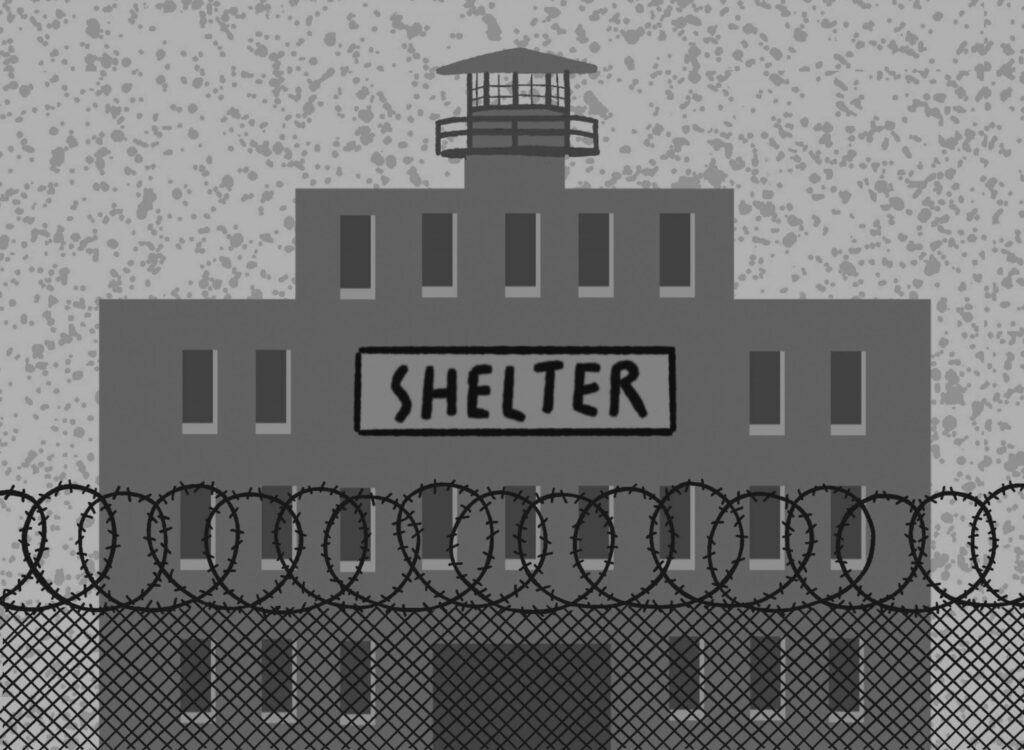

A place of respite or tantamount to a prison?

Jamie Bennett

A Complex Exile is about people like Norman and how shelters — through their regimented and security-oriented emphasis on personal responsibility — too often isolate and shame individuals who are already profoundly isolated and ashamed. Dej steadily challenges the shelter culture and its methods. “This book acts as a proverbial poking stick,” she writes, “curiously and persistently nudging and jostling these makers of exclusion to uncover what lies beneath.” I think a more accurate metaphor would be a ballistic missile.

According to Dej, who teaches criminology at Wilfrid Laurier University, shelters have become “neoliberal total institutions” within the “homelessness industrial complex.” She posits that they are tantamount to prisons, where discipline and social control deprive residents of autonomy and choice. As non-state actors that are modelled on “neoliberal governing rationales,” including surveillance, shelters are not in fact “an ethical, economically sensible, or practical response” to homelessness.

Wanda is aware that for housed people having a cup of tea and a piece of toast at one’s leisure is of no concern. At the shelter, however, where staff strictly control mealtimes and room access, Wanda’s request for food outside the schedule is a request rarely granted.

Dej suggests that the choices homeless people do have — to come and go as they please, to accept or refuse services as they wish, to opt out of the system completely — aren’t really choices at all when the only viable alternative is the street. Because they offer meaningless agency and control behaviour through “mortification processes” like denying simple requests, shelters are an insidious institution “crucial in the social control of those at risk of entering the criminal justice system.” Together, they “act as a holding place for individuals who cycle in and out of correctional systems.”

Dej also skewers the psychiatric models used in today’s shelter system. These, she argues, reaffirm for residents the idea that they are sick and oblige them to follow prescribed treatment protocols — a high bar that is too often out of reach for chronic shelter users. “The hope for inclusion,” she writes, “that encourages individuals experiencing homelessness to accept mental illness diagnoses, treatment (almost exclusively psychotropic medication), and the individualization of problems in living is often nothing more than that — hope.”

She illustrates her point with the experiences of Ron, a forty-one-year-old man with multiple diagnoses and addictions, who “seizes on the biological model of mental illness and addiction to make sense of his brain and provide a pathway for wellbeing.” The materials provided by his support group are designed to give him “hope and a sense of control over his life,” but in the absence of “adequate social supports,” the emphasis on self-regulation “provides little recourse to address the structural barriers Ron and others face.” Like the asylums of old, Dej says, the shelter system encourages medicalized intervention to manage illness and to discipline and control residents.

Dej did her post-doctoral work with the premier homelessness research hub in the country, the Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, hosted in Toronto at York University. Fittingly, A Complex Exile contains more than 300 references and draws upon forty-four interviews conducted at Crossroads and Haven shelters, in Ottawa, and on 296 hours of participant observation. To advance her thesis that the shelter’s purpose is more about control than cure, Dej invokes the concepts of redeemability and cruel hope, the inclusion-exclusion continuum, and consumerism, among others.

And therein lies a troubling flaw. By zooming in on the experiences of several dozen chronic homeless people and then zooming out — way out — to make conclusions about an organizational culture that, like some sort of Hotel California, allows residents to check out but never leave, Dej ends up losing sight of the formidable accomplishments of the majority of people who do move on to better times, and of the shelter staff who guide them on their journeys.

Initiatives like Shepherds of Good Hope’s managed alcohol program are doing wonders, as is Old Brewery’s PRISM program and our Le Pont project, an award-winning housing program. Indeed, my colleagues across the country are finding ways to help most of the people who come through our doors. But Dej makes few references to these efforts compared with the more theoretical, anti-establishment literature she relies on — some of which predates the neo-liberal age she so vehemently (and rightly) abhors.

With A Complex Exile, Dej does offer three key truths that the homelessness sector and anyone interested in the field would benefit from hearing.

First, she ably describes a complex reality: shelters are doing a disservice to people like Norman and may be assisting some residents with little more than spinning in circles. If an individual’s case is too tough, or “irredeemable” in Dej’s lexicon, workers may be quick to give up on them. Sometimes, we may prematurely bar them from our facilities for violating the rules or acting out. For the protection of all, staff do need to exert control within the shelter, but have we gone too far? If shelters were smaller, able to provide more privacy and had more lenient rules (like offering a cup of tea whenever someone asks for one), would we be more helpful to those we serve? I agree with Dej that new thinking and new approaches, like improved peer support, should be tried.

Second, the shelter sector too infrequently speaks out to defend the rights and interests of its residents, in part because shelters are wholly or partly funded by governments that are positioned to remove the structural barriers to secure affordable housing. By shying away from biting the hand that feeds them, shelters are protecting a status quo that is not working for many.

Finally, Dej is right that the larger sector, which includes more than just shelters, needs to stretch itself by doing more to help prevent homelessness in the first place. It is devastating for people to have to knock on the door of a place like the Old Brewery. Treating homelessness through case management and providing housing is clearly not working on its own. By using more upstream approaches, we may indeed help make homelessness the “rare and brief” experience it should be.

James Hughes is the editor of Beyond Shelters: Solutions to Homelessness in Canada from the Front Lines. He lives in Montreal.