You hear an earthquake before you feel it. The dishes in the cabinet start to rattle, the wood joists in your house scrape at each other. Then you feel the rumble and stumble to keep your balance as the floor shakes. Thirty seconds, a minute — more if you’re unlucky. Regardless, it feels like an eternity, and afterwards it takes minutes for your adrenaline levels to settle down.

That was my experience, at any rate, in the years that I lived in Los Angeles. Some of the quakes I experienced were of the dime-a-dozen variety, but then there were two in one day that were the strongest in forty years. Nothing in my vicinity was damaged in these temblors, but I gained stories to tell at dinner parties and learned to mimic my quake-experienced neighbours, who often pronounced, “It’s the price of living in paradise.” And, like a true Californian, I did nothing to prepare for the next one.

Those two things — the inevitability of earthquakes and the reluctance of most people to get ready — are at the core of Gregor Craigie’s On Borrowed Time: North America’s Next Big Quake. Craigie, a veteran journalist and the host of the CBC’s On the Island, in Victoria, is straight up about the goal of his book, and that’s to scare the living bejeezus out of enough of us that we subscribe to a massive program of retrofitting buildings and laying in supplies. He writes about some of the biggest disrupters in recent history — from San Francisco, California, and Christchurch, New Zealand, to Haiti, Japan, and China. His tour des horreurs offers compelling scenarios of flattened cities, piles of brick and rebar, surging tsunamis, and, most important, hundreds of thousands of people killed, injured, or left homeless. In fact, there’s such a similarity to the destruction that after a few chapters it’s hard to distinguish a rumbling Los Angeles from a shaking Anchorage or Tangshan.

Of course, Craigie’s larger point is that we are living “on borrowed time” because the Big One is coming. That’s the one in which a couple of the tectonic plates that form the earth’s crust violently push against each other and make life very miserable for anyone within a hundred miles of the epicentre. Craigie has interviewed countless experts in the past two decades, which gives him authority as he scouts the situation in North America in particularly chilling detail. But it’s clear that he is most interested, understandably, in Victoria, where a recent study outlined a worst-case scenario: two-thirds of the city’s buildings either collapsing or facing demolition.

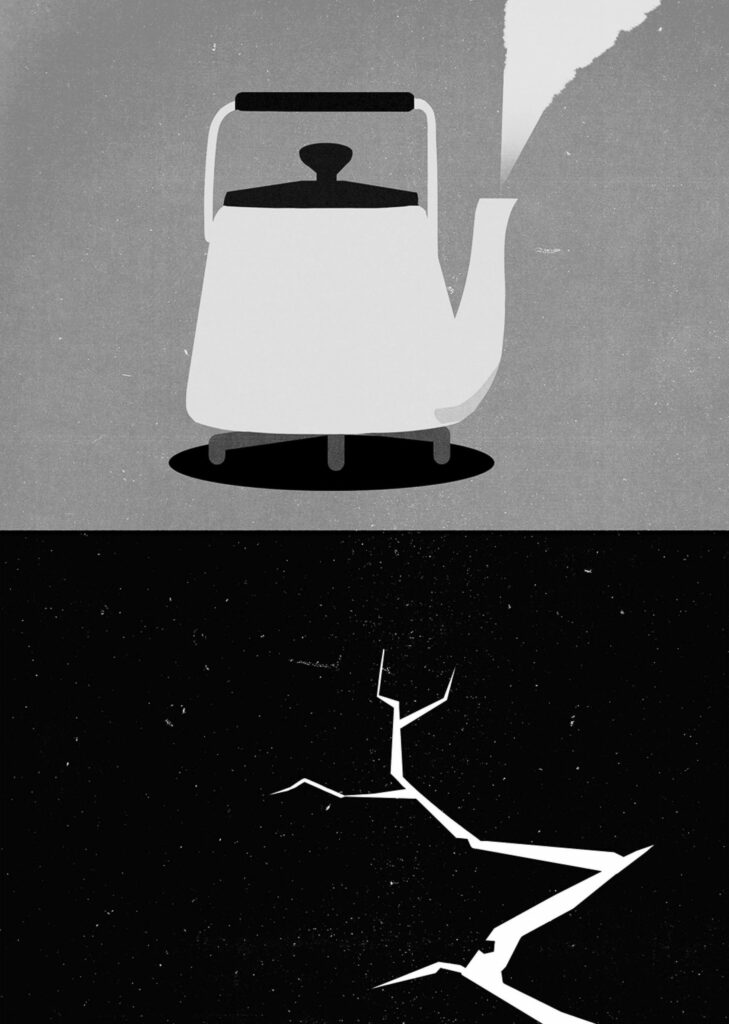

The pressure keeps building.

M.G.C.

Vancouver Island is at the northern edge of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, which Craigie describes as “a massive undersea fault that has produced some of the world’s biggest earthquakes — and will do so again.” The zone is susceptible to two different types of quakes: those that originate along a plate’s edge and those that originate within a plate’s interior. And though the seismic risk facing Victoria, Vancouver, and other coastal communities in British Columbia is formidable, the potential of catastrophe hasn’t been matched with preventive action. In 1993, the City of Vancouver identified more than a thousand buildings at risk of collapse during a major seismic event; nearly thirty years later, there’s no comprehensive strategy to retrofit them to withstand the jolt.

It’s a similar story in other cities in the Cascadia Zone. In 1995, Portland, Oregon, passed a bylaw that required the retrofitting of old brick buildings, the most vulnerable type in an earthquake. Only about 20 percent had been upgraded by 2015. It’s just as bad in Seattle, Washington, where the city has been trying since the 1970s to compel owners to strengthen their brick buildings: a thousand of them, with roughly 30,000 occupants, remain vulnerable. Craigie introduces us to Eric Holdeman, an official with Washington State, who has preached, with considerable zeal, the need to prepare. Holdeman isn’t ready to admit defeat, but he tells Craigie, in the driest possible way, “The one thing I’d say is missing is a sense of urgency.”

People shrug off the doomsayers because the cost of getting ready is high. They also don’t see the immediate point. Robert Gifford, a professor at the University of Victoria, calls such people the “Dragons of Inaction.” Craigie bemoans this widespread complacency as he lists the natural disasters — hurricanes, floods, and fires — clamouring for our attention. However, he throws “growing concern about climate change, ocean acidification, and falling fish stocks” into this mix, without acknowledging that the climate crisis is an existential threat in a way that earthquakes aren’t. San Francisco rebuilt itself after big quakes in 1905 and 1989, for example, and presumably it would find its feet if knocked down again. That resiliency is much less certain if the planet keeps warming.

Our rather blasé relationship to the Big One says much about how the human brain judges risk. In a word: badly. There’s a primitive part of the brain that processes base emotions by pumping out adrenaline — the fight-or-flight reaction. The more advanced neocortex, found only in mammals, governs a more nuanced approach that allows risk to be analyzed in the light. If you’re walking down a street and a chunk of masonry is falling overhead, you’re going to run. But if you’re walking down that same street thinking about the possible threat of an earthquake that could dislodge that same bit of masonry, you’re going to keep on walking because you’re not in imminent peril.

This type of thinking is evident in a 2019 study from Vancouver, in which researchers, convinced that people no longer respond to statistics that present abstract risk, thought they could scare people into action. They doctored pictures of older schools in the city to show what they would look like after an earthquake. It didn’t take much to imagine the children trapped inside, and the researchers found that participants were more likely — though not by a whole lot — to sign a petition to support seismic upgrades for schools. But seeing the pictures of damaged facilities, rather than just surveying the doomsaying statistics, didn’t alter anyone’s intention to prepare for an earthquake themselves or to support broader municipal programs.

As a species, it seems, we specialize in whistling past graveyards. And despite Gregor Craigie’s best efforts, the dragons of inaction may not be slain for a while yet.

Murray Campbell is a contributing editor to the Literary Review of Canada.