Sinclair Ross’s As for Me and My House is a classic. Published in 1941 by the American firm Reynal and Hitchcock, the story follows Philip Bentley, a preacher and a newcomer to the small town of Horizon, and his wife, Mrs. Bentley, who narrates it in the form of a diary. Gloomy and Canadian — insofar as you don’t get a happy ending, just recognition of the familiar — the novel is an example of the “prairie gothic,” where characters who have notions of escaping their situations are trapped, physically and spiritually. Philip is unhappy, very unhappy, but he doesn’t have or won’t provide the words to explain why. Mrs. Bentley spends the narrative, and presumably her whole married life, trying to understand his pain.

As for Me and My House has served as inspiration for other works of quiet desperation. Lorna Crozier’s 1996 poetry collection, A Saving Grace, channelled the voice of Mrs. Bentley to paint a terse picture of prairie life. Few words in these poems are longer than one or two syllables. True to the subject, anything more would be ornamental. If you can’t say it simply, it doesn’t need to be said. This is the language of rural Saskatchewan and Manitoba (or it used to be): an economy of common sense. Go ahead and talk about the weather, but the rest, kindly, is none of your business. In “Dust,” Mrs. Bentley stuffs rags in the window gaps “as if they were wounds / that needed staunching.” It’s a hopeless attempt. The winter chill is too much, as is the root of the metaphor: these are emotional wounds too. It’s none of our business, and she won’t talk about it, but we can read between the lines.

Now, with his fourth novel, The Beautiful Place, Lee Gowan lets us return to these characters once again. Set in near-contemporary Vancouver and Toronto, the self-described sequel to As for Me and My House centres on a possibly suicidal cryonics salesman with two troubled marriages and counting (cryonics being the technology that allows you to freeze your body, or just your head, until the cause of death can be cured). Through his work, he meets a young woman who sees Jesus and Buddha in her dreams and brings messages from beyond the grave. This salesman also happens to be the grandson of Philip Bentley. But it’s as if the Philip from Ross’s work has got off the train at the wrong station: here, the prairie gothic becomes an urban farce. The two books don’t have much to do with each other, and perhaps that’s for the best.

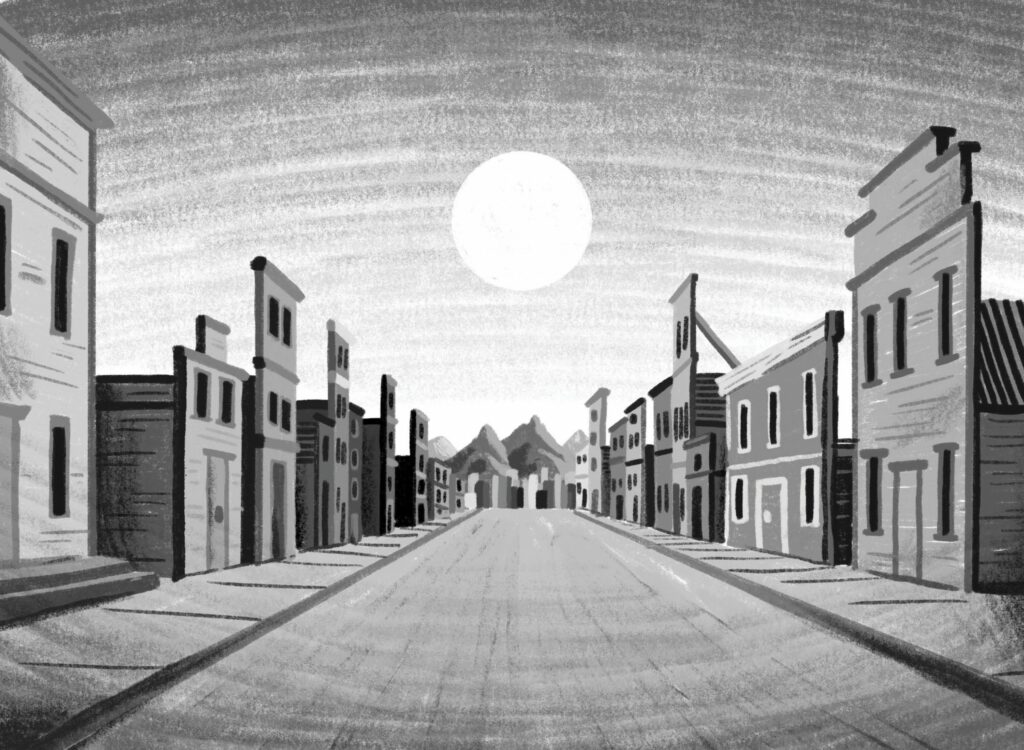

They used to teach As for Me and My House in junior high school in Winnipeg. The language is simple. It’s set in the Depression. The plot is suited to the place and time: low on action, heavy on psychic tension. Philip Bentley has just been posted to Horizon, the sort of town where Main Street is lined with false fronts, which make the buildings look taller, more imposing, like the stores in old westerns. He’s a preacher, a job for which he is neither suited nor enthusiastic. He likes to draw in his spare time, especially sketches of those shops downtown. The religious life is a gig, like being a carpenter: every community needs one. But as newcomers, the Bentleys attract attention. “People in a little town like this grow tired of one another,” Mrs. Bentley writes in her diary. “They become worn so bare and colorless with too much knowing that a newcomer like Philip is an event in their lives.”

Previous church assignments haven’t worked out. Philip has trouble fitting in: “He hasn’t learned yet to be bland,” to disappear in a very small crowd. In Horizon, the false fronts become a screaming metaphor: they “ought to be laughed at, never understood or pitied. They’re such outlandish things, the front of the store built up to look like a second storey. They ought always to be seen that way, pretentious, ridiculous, never as Philip sees them.” Mrs. Bentley is talking about the people of Horizon, of course, but is she speaking about Philip, too? Junior high school students can be expected to knock such questions out of the park, but in fact the deeper you go on Philip, the harder he is to figure out.

Something has happened to his sketches, we are told, since the move to Horizon. “There used to be feeling and humanity,” Mrs. Bentley explains. “Now everything is distorted, intensified, alive with thin, cold, bitter life.” At times she sees Philip standing outside, hatless, against the wind, to no real purpose, his shoulders sagging. Mrs. Bentley loves her husband, that much is clear; but the reader soon grows tired of his sulking — not because Ross fails at his task but rather because of his artistry. The man is depressed. But why?

Not necessarily as advertised.

Alexander MacAskill

Soon Mrs. Bentley meets Paul, a teacher with a crossword solver’s obsession with language and words and the trivia behind them. He becomes a friend, someone to talk to in lieu of any conversation at home. Through Paul, she is introduced to Steve, a local kid with a troubled background: he’s an orphan without a foster family.

In time, the connection between Steve and the Bentleys grows intricate, and somehow Steve begins to melt the emotional ice with which Philip insists on encasing himself. They aim to adopt him. But Mrs. Bentley observes, innocently, that her husband likes to place his hands on Steve’s shoulders, and the reader starts to get the idea: behind Philip’s false front are taboos that are beyond acknowledgement in such a place. Soon enough, Steve has to go away to a Catholic orphanage.

The tale ends with the birth of a child, a son: it’s Biblical. The boy is Philip’s but Mrs. Bentley is not the mother. Suffice to say that this turn of events provides her an opportunity for escape, from Horizon, from Philip and his secrets, yet instead she stays. It’s that prairie gothic again: “He’s helpless,” she writes. “He needs me.” She means the newborn, though it applies to her husband too. The happy ending is deferred, as so often occurs in Canadian literature of the mid-twentieth century.

We never learn Mrs. Bentley’s first name. As the writer Robert Kroetsch observed of the novel, this omission is part of the “splendid dance of its evasions.” Lorna Crozier, for her part, calls Mrs. Bentley “one of the most enigmatic and controversial figures in Canadian literature.” And it’s true that she lingers after being read: one can cheer for her, half knowing that she’ll make the wrong choice by staying in Horizon, but also find a wisdom and inevitability in the fact that on the prairies (or anywhere?), there’s nothing worse than being alone.

Mrs. Bentley is barely to be found in The Beautiful Place. Fair enough: it’s Lee Gowan’s book, not Sinclair Ross’s. The new work is also told as a diary, and the contrived author is Philip’s grandson, the son of the boy born at the end of As for Me And My House. He addresses his entries to a woman named Mary Abraham, the wife of a client at the cryonics facility — called the Beautiful Place. Her husband has lately been frozen, perhaps against his wishes. Mary is young enough to be mistaken for the dead man’s daughter. By the third page, Chekhov style, there is a pistol (which once belonged to Philip). Mary Abraham is a mystery, and the narrative soon takes on the colour of noir: she is a less talkative, more gnostic version of Lauren Bacall’s character in Howard Hawks’s film The Big Sleep. As noted, Mary dreams of Jesus and Buddha and considers them real enough; she treats religious figures as if she is meeting influential businesspeople at a cocktail party.

Through flashbacks, we encounter Philip Bentley as an elderly man in Vancouver in the 1980s, then a retired artist of notable abstract works, which hang in the city’s art gallery alongside paintings by Emily Carr, and earlier realist pieces — the prairie landscapes of the preacher days — that no one wants to buy. Stories past and present converge, and we assume that at some point the gun will go off.

The Beautiful Place carries effective descriptions of characters and scenes. It wants to be a bit bonkers but reaches, often, for the safety of cliché, especially in dialogue (“Look, we’re all in this together, so there needs to be some house rules”). To Gowan’s credit, it doesn’t pretend to be more than it is: an imagined yarn about capably sketched and structured situations that some might agree are amusing. And it does possess a kind of narrative momentum.

It’s not the prairie gothic, though. The desperation to plug the gaps to keep out the cold isn’t there. Sinclair Ross was interested in people — people like him and the people who misunderstood him. What mattered was their joys and sadness, but their sadness above all else. The Beautiful Place is a benign romp. There’s a place on the shelf for both titles; just don’t bother to try to connect them.

Tom Jokinen lives and writes in Winnipeg.