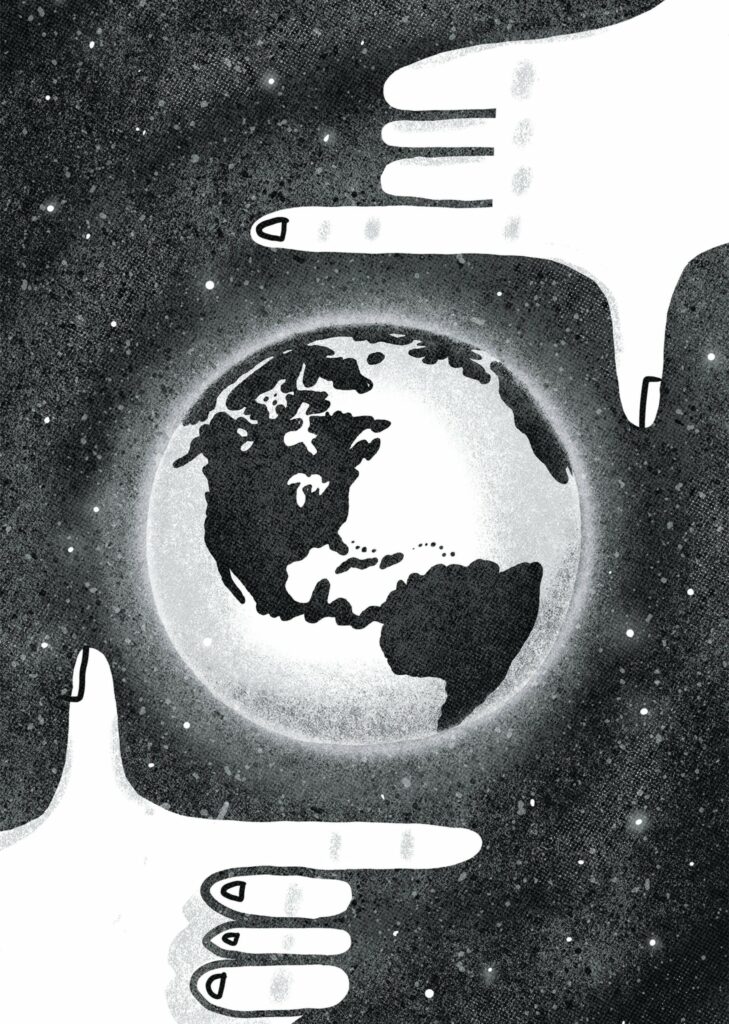

Sheila Heti is anything but predictable. Her latest novel meditates on friendship, intimacy, and identity through the frame of God, a disgruntled artist, as he stands back to contemplate his first draft of existence. After a long delay, the Lord decides to tear his design apart: the earth is obviously flawed. But before he scraps all living things entirely, he manifests himself as three art critics in the sky —“a large bird who critiques from above, a large fish who critiques from the middle, and a large bear who critiques while cradling creation in its arms”— to gain varying perspectives on what went wrong.

It is in this critical period of reflection and revision that we meet Mira, an art student born of a bird egg. People are also divided into three types: birds are sensitive, flighty souls who “consider the world as if from a distance”; fish are “concerned with fairness and justice” for all; and bears are driven to care for and protect their own. Despite her generation’s cynicism and aptitude for diagnostic proclamations, Mira finds beauty in the immovable truth of love. Still, the planet is heating up before its destruction. The seasons have become postmodern; the weather no longer indicates a place in the calendar year. Multiple species are dying. Mira’s contemporaries are envious and angry all the time. And everyone in Pure Colour is frantically crafting plays, stories, and movies to show one another — and God — what they think the second draft of life should look like.

In simple language that is lyrical and full of Heti’s wry humour, Pure Colour offers a glimpse into Mira’s world and then just past it. Everyday moments present gifts of rapture, such as the flowers on her windowsill that “make us think of the flowers in the soul of the person who put them there.” A favourite lamp is chosen for the “essential humility” of its design: “It had not been made by someone who imagined that an object fit into a greater system of values.” It had been made by someone “who simply thought, Now I will make my next lamp.”

A work that’s obviously flawed.

Sandi Falconer

Despite the novel’s surreal set-up, a shimmering quality of sincerity and authenticity shines through every encounter. When Annie, an American student who lives in a sprawling rat-infested apartment above an occult bookstore, enters Mira’s life, a window is blown open in the deepest corner of her chest. Mira discovers a new dimension of connection that is painful, strange, and lovely all at once. Their relationship has everything a coming-of-age romance should have: passion, desire, jealousy, despair. That Annie is a “distant fish” who was raised in an orphanage in some far-flung unknown city only adds to her allure. But when the death of Mira’s father threatens to tear apart the fabric of her existence, Annie’s cold hands, capable of addressing large-scale systemic injustices better than granular, emotional ones, provide little comfort.

The story is hard to pin down. Equal parts philosophy, fable, art criticism, mysticism, and elegy, the expansive plot — if one can call it that — escapes classification and instead follows its own course of astonishment and wonder. “It’s boring to do the same thing over and over again,” Heti said in an interview with The Cardiff Review, in 2018. “My writing comes out of a curiosity about something, a subject or a form or an approach or a method: can a book be written this way?”

About Pure Colour — a work in which the protagonist spends roughly forty pages sharing dual consciousness with her late father inside a leaf — some would say that, no, a book can’t be written this way. But the peril, the madness of these pages is only part of the novel’s larger commitment to addressing grief in all its befuddled and conflicting layers.

Mira’s quest is not to understand her sorrow, as the novel’s ominous “fixers” try to force her to do, but to feel it and to keep hold of her father’s spirit without losing possession of her own. These “fixers” come from the world of psychology and are the nearest thing to a villain the young heroine faces in her journey through the first draft. Their clinical approach challenges the strangely conservative conclusion she comes to during her time in the leaf: that “to follow the family traditions” with faith and love is the reason why we’re here.

Although God departs the narrative after the opening pages, Mira’s father, a different kind of patriarch — but one who also cradles creation — stays in her heart and mind to the very end. He dies before his daughter can reconcile their troubled relationship, which was ill-fated from the start owing to their conflicting natures: his smothering bearishness and her fragile flightiness. “Like God standing back from the canvas,” Mira must learn to regard her grief and guilt from the right distance. “For you can’t see anything if you’re too up close, and you can’t see anything if you’re too far back.” By adjusting her perspective, Mira is able to confront her father’s absence without letting it overwhelm her. She is able to love her dad for who he is, not just for the fact that he is her parent.

Though Pure Colour takes an unconventional route, its lessons are grounded in tenderness and hope. As they fumble through their relationships, Heti’s characters represent the “stumblingest” parts of being human. “Are you sad to be living in the first draft — shoddily made, rushed, exuberant, malformed?” the mysterious narrator asks in the latter half. “No,” the same voice answers, “you are proud to be strong enough to be living here now.” Even though there may be a better world to come, the second draft will never be as scrappy and exciting as the first.

As much as the story is about Mira, it’s equally about the artist — the artist who considers a subject from different angles, different heights in an attempt to capture it. One of the many writing hats Heti wears — she has published novels, plays, and children’s stories — is that of interviewer. In the past, she has claimed that she saw everybody as an oracle, an authority. With her newest work, she expands her investigative scope to encompass animals, plants, weather, even the cosmos. Pure Colour, which has only a few moments of direct exchange among its handful of characters, is rather a conversation with the universe. The realization is that “what is lovable is not humans, but life,” and that we are all small parts of a beautiful, flawed, and frequently baffling whole.

Clayton Longstaff lives in Victoria.