Before Margaret Atwood the Icon was an icon, she was a little girl — born in November 1939, at the end of the Great Depression and two and a half months after Nazi tanks rolled into Poland. A little girl who spent her childhood shuttling between the wild summer bush of northern Quebec and the windy wintery landscapes of several nondescript 1940s cities, including Ottawa, Sault Ste. Marie, and Toronto. A little girl who had a meticulous, scientific father, an entomologist who worked for the Department of Lands and Forests, and a highly literate mother, a former nutritionist. A little girl who, following her parents’ example, was a voracious reader. Margaret Atwood was a little girl who, after a period of struggle, doubt, and uncertainty, developed into an extraordinarily articulate and cultured woman: a scholar, a writer, a poet, and a literary genius known throughout the world.

Early on, young Atwood appreciated the scientific method and the importance of observing things closely, particularly bugs and trees. She was aware of nature in all its untamed glory, rawness, and danger and of the crucial role of terminology, of taxonomy, of classifying everything systematically, and of using precise, no-nonsense language. She was also acutely conscious of the contrast between urban life, where nature seemed alien and far away, something to be conquered and tamed and exploited, and life in the wild, where she realized that she, just like the beetles and conifers and beavers, was an integral part of things — a tiny, vulnerable, mostly helpless part.

Until she was twelve, Atwood didn’t attend school full-time. Life was too nomadic. Often alone in the wilderness with her family, in a world without television or computers or iPhones, she consumed book after book. Cheap mass paperbacks of the classics and popular literature, often with enticingly lurid covers, began appearing in the ’40s. These made it possible for a girl in the woods to educate herself in a vast range of tastes and tales, from pulp and pop to Dickens and Shakespeare. The bare simplicities of living in the bush — in contrast to the distracting multifariousness of cities — can make the core narratives of life and death seem as clear as crystal. And they may give such a girl a taste for the enticingly knowable — archetypical — transparency of myth and fairy tales.

After graduating from high school, Atwood studied at Victoria College, part of the University of Toronto and a centre of critical excellence. This was the home of Jay Macpherson, the brilliant mythopoeic poet, and of Northrop Frye, the acclaimed theorist. Such influences deepened Atwood’s interest in taxonomy, in myth and fairy tale, in basic literary forms, and in the anthropological roots of culture. Graduating from Victoria and winning a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship, she leaped onward to Radcliffe College, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she gained a master’s degree in 1962 and began a doctoral project on metaphysical romances. But after two years she abandoned the thesis for writing and teaching.

The necessity of understanding the imagination.

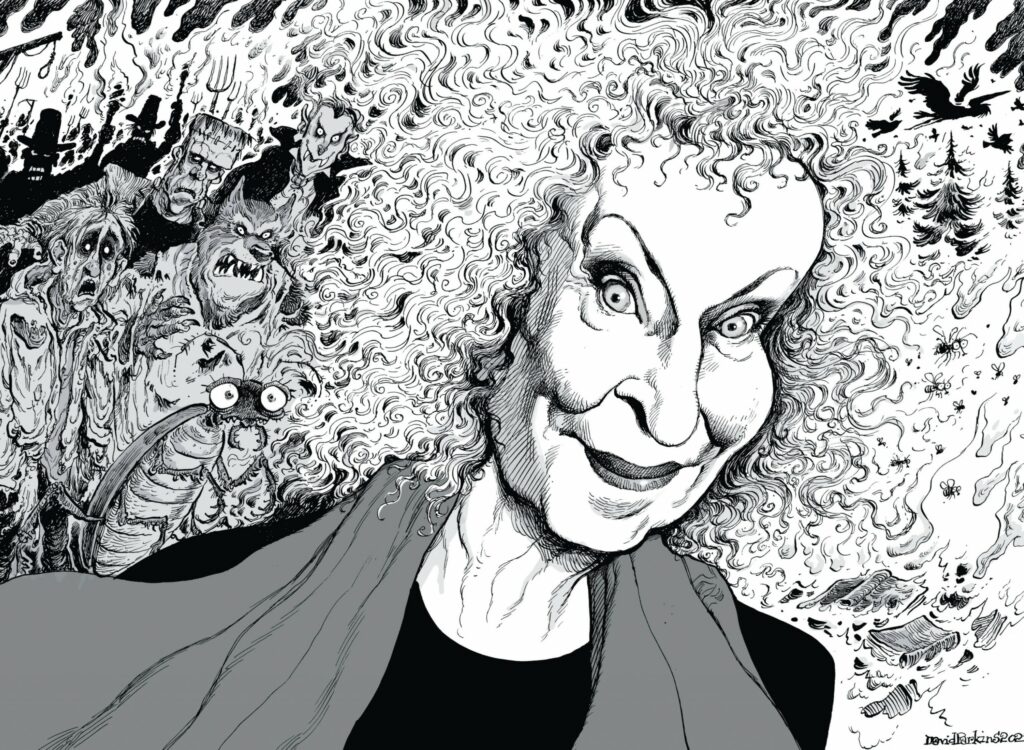

David Parkins

Burning Questions is a collection of work that ranges from 2004, the year George W. Bush was re-elected as president of the United States, to pandemic-inflected 2021. Atwood, long since a full-fledged icon, covers a vast range of subjects, and in almost every text we see echoes of her childhood and youth. She demonstrates what seems to be an extraordinary episodic memory for what happened when and where and how, and she almost always situates her experiences and discoveries, what she read and whom she met and what she did, firmly in the social history of the day: the hit songs, pop culture, and literature. Burning Questions is, among other things, a time machine. It scrupulously avoids nostalgia, but it can also call up fond or painful memories.

Atwood has written speculative fiction throughout her career, and here she explores the seemingly oxymoronic term “science fiction.” How can science, which deals in facts, be mingled with fiction, which is mere make-believe? To clarify the issue, she anatomizes the difference between “truth” in fiction and “truth” in science, and along the way she defends literature and imagination against the dusty philistine — and rather Canadian — cult of bare, unadorned facts.

Science, Atwood explains, provides the tools and technologies to realize our dreams. But imagination, as bodied forth in the arts and in literature, gives us those dreams in the first place. Without imagination, the source of all our energies, we would be flying blind with no destination; we would be, to borrow a phrase from John Ralston Saul, an “unconscious civilization.”

In many places in these collected essays, notably in her witty discussion of debt, Atwood anticipates Yuval Noah Harari’s idea, put forth in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, that our ability to create fictional entities — such as nations, armies, religions, and currencies — is the most powerful weapon we have. By believing fervently in these imaginary structures, we magically make them real: we wave flags, we take up guns, we kneel before pieces of wood, and we trade mere symbols — dollars or euros or yen — for the realities of food and shelter.

Mobilizing her talent for definitions and taxonomy, Atwood fine-tunes the distinction between “science fiction” and “speculative fiction.” She takes us on a tour of utopias and dystopias, giving a nuanced reading of George Orwell’s 1984. Ultimately, it is an optimistic book, she argues, since the description of the dystopia is written as the history of a now dead society: the particular hell of the year 1984 is in the past. She also takes up Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian novel We, which he wrote during the Russian Civil War. Anticipating “the Soviet repressions to come,” Zamyatin showed how a society designed to create total happiness can instead produce — quelle surprise — a tyranny.

Atwood’s explanation of the genesis and structure of her own speculative fiction is fascinating. She gives us the background to her groundbreaking cult classic, The Handmaid’s Tale, published in 1985. The tale now seems prophetic: it envisages, in dystopian form, the rise of the anti-feminist, misogynist, fundamentalist Christian Right that we can see proceeding apace in the third decade of the twenty-first century. She also describes the literary and thematic background of her post-apocalyptic trilogy that began with Oryx and Crake, which depicts a world inhabited by biologically modified humans and animals, and continued with The Year of the Flood, which centres on an environmental sect known as God’s Gardeners. She concluded the trilogy in 2013, ten years after she started, with MaddAddam, which “fills us in on the past of a character who isn’t explored thoroughly in the first two books.”

Woven into the trilogy are urgent — indeed, burning — questions: What are the possibilities and perils of revolutionary new technologies? What will climate change and ecological crises do to the planet and to the human race? What is democracy, and will it survive? The role of fiction in answering such questions is essential. The future does not exist; imagination does. Presented to us as an imaginary space, the future is a web of delights and horrors. Wielding the instrument of fiction, Atwood, like other intrepid explorers, takes us on a monitory voyage and gifts us with a sizzling warning.

Those cheap paperbacks out in the woods opened the door to pop culture for young Margaret Atwood — a door that never closed. Far from being a literary snob, this big-time award winner is an omnivorous egalitarian. We learn, for example, when she first encountered zombies, werewolves, and vampires. She even gives us a shopper’s guide to monsters, with the pluses and minuses of each model.

Atwood has fun explaining why old people invariably want to give advice — all that wisdom bottled up in a steam cooker without a safety valve — and why young people invariably don’t want to hear it. In a moving piece titled “Somebody’s Daughter,” she recalls a two-week literacy and sewing camp in Nunavut, and how the Inuit women who came to participate suddenly found their voices when they were given an audience: other women in the world. We are always writing for someone, Atwood says.

Burning Questions speaks to the rise and fall and rise again of feminism and the fluctuating fortunes of women’s rights, including the ways they can so easily be reversed. Atwood examines how various ideologies, prominent among them the major religions, have been used by men to justify lording it over women for millennia. Wars and revolutions sometimes liberate the ladies, but then, when the dust settles, they’re marched back into the kitchen. She also explores the concept of beauty, how she discovered it as a child, how it impacted her, and how it impacts other young women — whether back then or now, in the age of Instagram and Facebook.

The collection includes Atwood’s vividly etched portraits and brilliant thumbnail analyses of illustrious writers and extraordinary personalities, such as Gabrielle Roy, Marie-Claire Blais, Ursula K. Le Guin, Ray Bradbury, Isak Dinesen, Lucy Maud Montgomery, Hilary Mantel, Rachel Carson, Stephen King, and Doris Lessing. Among these is a warm, unsentimental, amusing, very affectionate portrait of her late partner, Graeme Gibson, the cultural organizer, birdwatcher, idealist, and author of the novels Five Legs, Communion, Perpetual Motion, and Gentleman Death, as well as The Bedside Book of Birds. Gibson was a naturalist, conservationist, farmer, and enthusiast — and a true gentleman.

Many of the women writers Atwood discusses were also born in the back of beyond and went on to conquer the distant cosmopolitan citadels of high culture. But Alice Munro provides the most enlightening contrast to Atwood’s own experience and career.

Munro was born almost a decade before Atwood, in 1931, at the beginning of the Great Depression, in Huron County in southwestern Ontario. Atwood describes this region as full of “lush nature, repressed emotions, respectable fronts, hidden sexual excesses, outbreaks of violence, lurid crimes, long-held grudges, strange rumours.” This is the land of the southern Ontario gothic, and when you leave, Atwood seems to suggest, you take the gothic with you.

Munro is divided in her writing: she has a Presbyterian side, specializing in minutely detailed and merciless self-examination, and an Anglican side, acutely aware of the finest gradations of small-town, colonial, and snobbish social distinctions. These elements find their way, Atwood points out, into Munro’s style and her manipulation of point of view, which moves between different voices and perspectives. Munro the writer also carries within her a hectoring philistine voice, rising like a demon from the raw puritan depths of Huron County, a voice that declares that literature is a useless frill and that you, the writer, are a fraud.

Atwood constantly demonstrates that she is aware of this badgering philistine voice herself, but because she grew up slightly later, in a family that was a bulwark of science and literacy, her battle with the philistines is conducted with a light, ironic touch. Indeed, her work illustrates how an inner philistine can keep you grounded.

Margaret Atwood, like any great novelist or poet, speaks with many voices. Throughout Burning Questions, she conducts her chorus with a firm hand. She invents her persona, plays with it, shifts perspectives, and twirls around like an impish ballerina, leaving a trail of irony behind. The little girl in the woods — entranced by fairy tales, swept up with Dorothy in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, fascinated by nature in all its threatened grandeur — is still very much alive.

With Burning Questions, a book to dip into, to savour, to ponder, the one-time little girl has issued a very sophisticated call to arms — so that we might defend and restore the planet and humanity itself.

Gilbert Reid is a writer for television and radio.