The Omicron variant caused plenty of drama for Quebec’s theatre industry. On December 20, 2021, the premier, François Legault, shuttered all performance venues with four hours’ notice. They were permitted to reopen in February at half capacity, with the ironic result that the most popular shows were cancelled, as there was no fair way to distribute the tickets. For an art form that depends on physical presence for much of its appeal, the pandemic has been punishing. Against this backdrop, spending time with plays recently published by Atelier 10 is both a reminder of what’s been lost and a source of hope for what’s to come.

Atelier 10 is a Montreal collective, supported by the Université du Québec à Montréal, that releases the twice-yearly cultural magazine Nouveau projet, as well as Documents, a series of essays on contemporary social dilemmas. The most original of its offerings, however, is Pièces, a series that features new drama. Three or four volumes are issued each year; they can be bought individually or as part of subscriptions that include Atelier 10’s other publications. Through the alchemy of grants and sales, Pièces has now reached its tenth year.

The model is clever. Even though I’m a voracious reader and theatregoer, there are few published plays on my shelves at home. Most of those have names like Chekhov and Euripides on their spines. But bundle contemporary drama with Quebec’s rough equivalent of The New Yorker, and I’m down with updating my library. The series also benefits living playwrights hoping their work might be taught or restaged, and its recent offerings bear witness to the ways — both subtle and direct — the province’s theatre scene has been forced to adapt.

François Grisé’s Tout inclus (All-inclusive) deals with life in seniors’ residences and has become tragically topical as of late. But the initial inspiration was personal. When Grisé’s parents moved into such a residence, the shift seemed traumatic; he describes them as “uprooted objects, lined up against the wall alongside what was left of their dismantled house.” He was in his early forties at the time and felt as though he had “unplugged from the matrix.” He decided to move into a seniors’ home to experience the environment himself.

In the works since 2014, Tout inclus premiered in 2019, well before the mass deaths in Quebec’s long-term-care homes, or CHSLDs, became front-page news. Appropriately, the opening scene now reminds audiences that 95 percent of people who died of COVID-19 during the first wave in Quebec were over sixty-five — and that two-thirds of them lived in CHSLDs.

The play depicts the month that Grisé, who played himself in the premiere, lived in the Jardins du Patrimoine in Val-d’Or. (His parents’ residence, like dozens of others, turned down the playwright’s request to move in, likely out of fear of a scandalous exposé.) Grisé’s approach proves more experiential than investigative, and more humanist than activist. He details his daily routine, including the shifting cafeteria menu, which becomes a motif for his loss of autonomy. And he asks his new neighbours why they left their previous dwellings and what they think of life in a facility exclusively for the old. Most often, they dodge the question to tell him other stories.

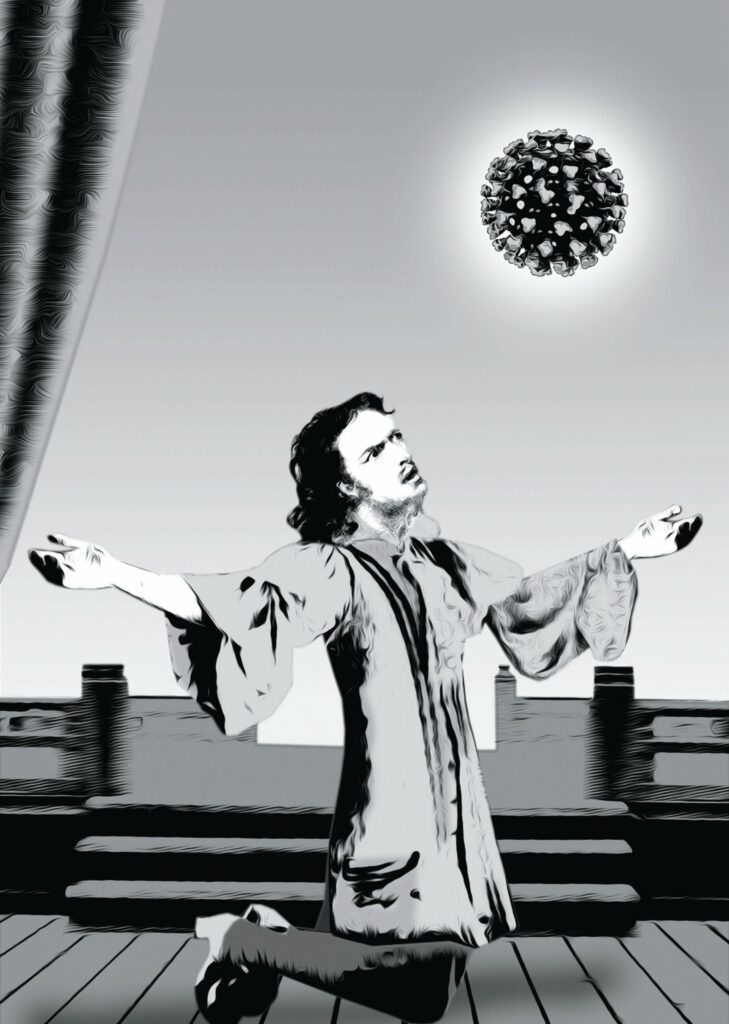

A plague of sighing and grief.

Pierre-Paul Pariseau

There is a productive tension between Grisé’s portraits of strangers and his strained telephone calls with his parents, burdened by the accumulation of family dynamics. Of his new contacts, Madame Deschambeault stands out as a sort of impossible love interest: she is eighty-nine, smelling “a bit like pee” but with “beautiful brown eyes.” (Grisé, a gay man, observes, “It sucks that she isn’t forty years younger and not called Monsieur Deschambeault, because I could have married her.”) Foregrounding Deschambeault’s age and physical condition may seem degrading, but in context it reinforces the play’s confrontation with bodily decay. In fact, Grisé periodically reports that many of his former housemates are no longer alive. Audience members are also asked to reflect on their own condition: during productions, they are seated by age, with the oldest at the front.

Tout inclus juxtaposes pathos with dark humour, as when Grisé compares the Jardins du Patrimoine to a David Lynch film, with its fluorescent lights and smell of wax, gravy, and chlorine. He memorably describes his life there as “like being in a play by Michel Tremblay. . . and Samuel Beckett . . . staged by a theatre postdoc at UQAM.” Of course, the observation leads to the question of whether such eerie environments are the best way to live out one’s final years. While Grisé laments the lack of public facilities for seniors, his play isn’t exactly a searing critique of the industries that develop around elder care. Given how depressing the private venues are, it is unclear how a public option would be an improvement. Ultimately, Tout inclus is torn between the inevitability of death and the desire to make the last stages of life meaningful. The lack of conclusion strengthens the work, which in any case is subtitled “Volume 1,” with the promise of more to come.

The pandemic is the explicit subject of Le besoin fou d l’autre (The insane need for the other), an anthology of projects that includes several from the summer of 2020, during the lull between the first and second waves. Interspersed with photographs of shuttered theatres, the gathered pieces speak to frenzied efforts to cope with new circumstances. Some are designed for outdoor performance or for tiny audiences, while others take the form of monologues. The creative range is impressive, though the editor Valérie Deault’s prefatory claim that the artists have “surpassed themselves” might be too flattering. Like much pandemic art, the collection risks feeling ephemeral, and it testifies more to the fragmentation of a community than to the liberating nature of constraints.

The longest excerpt, “Ensemble” (Together), comes from a participatory play about the first wave. In performance, socially distanced audience members are seated outside with headphones and listen to pre-recorded actors. Each performer has a number, and when it is called, he or she stands up and briefly incarnates a specific recorded role. The characters are derived from a range of interviews, including with exhausted community workers, cheating high school students, and, briefly, a conspiracy theorist. The most moving segment features a woman who sneaks people into nursing homes so their loved ones will not die alone. At various intervals, the spectators are polled on their experiences. Some questions are trivial: “Who, on Zoom, has spent more time looking at themselves than at their interlocutor?” Others are existential: “Who has mourned the death of their career while asking themselves what they would do when all of this was over?” The material is rich and the concept inventive, but it’s so tied to a time and place that it already feels dated.

Another piece, “Vers solitaire” (Solitary verse/worm), is structured around guided walks. An audience member follows an actor, and both use headphones to listen to a soundscape designed for their route. In the atmospheric “Le pommetier” (The crabapple tree), groups of four move through several rooms to glimpse fragments in the life of an old man, before a longer encounter with his widow. Above all, Le besoin fou presents monologues. Some are realist and colloquial, others lyrical and impressionistic, but there is only so much a long speech can accomplish. One finishes the collection yearning not so much for dialogue as for that element so frequently lacking in both the experience of the pandemic and its retelling: plot.

There is plenty of plot in Véronique Côté’s La paix des femmes (Women’s peace/pact). The title references a 1999 Swedish law that decriminalized the sale of sex but penalized buying it, and indeed the play deals with prostitution. Here, too, the pandemic casts its shadow: La paix des femmes has not yet been performed. Its debut, once scheduled for January 2022 in Quebec City, is now set for September. An introductory note about “inevitable adjustments during rehearsals” might call into question Atelier 10’s decision to publish the piece early, but it also serves as a reminder of the backlog of much-delayed projects.

Côté’s work grapples with the moral stakes of sex work for women by questioning how much agency those involved in the trade actually have. Unexpectedly, her cast is dominated by middle-class intellectuals and artists: CEGEP teachers, a university professor, a journalist, a comedian, all presumably white and heterosexual francophones. Early in the play, they are preparing sushi, likely in order to highlight their relative privilege. Although one could criticize this focus, it does allow Côté to insist that prostitution touches all social circles, not just the marginalized.

At one point, a woman discovers that her partner ended up at a party with escorts and engaged with them. As she exclaims, “Before, I asked myself, who is it, who pays for sex? The clients, who are they? Well, there you have it. The client, he’s my boyfriend.” Elsewhere, a feminist professor named Isabelle is confronted by Alice, the sister of a former student who has died of an overdose months after becoming an escort. Alice blames Isabelle for having normalized sex work and ignoring its sordid realities: “The young girls, the young women out there, in your classroom, well there’s a bunch who think prostitution, it’s edgy, it’s glamorous, it’s a good way to make big money and even better, even better, it makes for good fiction!” The exchange is haunted by the memory of Nelly Arcan, the Quebec writer whose semi-autobiographical debut, Putain (Whore), chronicles her work as an escort while studying literature at UQAM. Arcan’s book took off, but her media image remained heavily sexualized, and she died by suicide in 2009.

The issue of prostitution is a major concern for Véronique Côté, who also co-authored an essay with Martine B. Côté (no relation) on the subject for Atelier 10’s Documents series. In s Faire corps: Guerre et paix autour de la prostitution en tant que fatalité (Esprit du corps: War and peace around the inevitability of prostitution), which was released around the same time as the play, the writers take a strong stance against viewing sex work as an occupation like any other. Instead, they claim the industry should be eliminated as much as possible, as it inevitably exploits women, who make up the majority of sex workers, for the benefit of mostly male clients. This is delicate terrain, and the two explain how the issue has split feminist camps. It is to Véronique Côté’s credit that her stance is less obvious in La paix des femmes. The play retains just enough ambiguity to expose the contradictions within feminist approaches to sexuality rather than resolving them. At least, that is how it reads on the page.

Ultimately, Atelier 10’s Pièces series is more than simple consolation during a time when stages across the country have been in disarray. Its existence speaks to the vitality of one province’s theatre scene and to a shared commitment to telling local stories. Some of these plays will age better than others, but all engage their moment with urgency and particularity. Certainly, the whole endeavour is worth a few rounds of applause.

Amanda Perry teaches literature at Champlain College Saint-Lambert and Concordia University.