After Olivia Robinson hijacks the keynote presentation at a company conference to share her colleague Osman Shah’s story of a past “tangle” with airport security, she asks the room of upper managers, “Are we really valuing diversity? Are we channelling the fullness of the experience of our Osmans?” The hapless narrator of Naben Ruthnum’s acerbic novel, A Hero of Our Time, has been played at his own game. The power of Osman’s ordeal — which he used to recount as “more of a joke”— has been subsumed into someone else’s narrative. “I see your faces now in this crowd as I admit I never have before,” Olivia says, in a speech that fast-tracks her to the top of the corporate ladder.

Olivia’s leadership “coup” is hidden in an apology, in her acknowledgment of her own cultural naïveté about inclusion at AAP, a company whose name Ruthnum never feels the need to spell out. But her co-workers are, to some extent, in on the ruse of this “enlightenment” tale. They accept her bid at concealment: “They saw the attempt but also the quality of its packaging, and they allowed that exterior to become the reality.” As icing on the cake, Olivia differentiates herself with a backstory of a cancer diagnosis, which ensures that her relentless ambition is always cloaked in a degree of awe for what she has achieved, given all that she’s endured.

A Hero of Our Time is a satirical rendering of a corporate world struggling to bridge the gap between preaching and practising, but it is also about the stories people tell to make use of their past and reshape their future. With her combination of progressive rhetoric — taking “the right shallow dips into shame and corporate self-interrogation”— and ruthless adherence to getting what she wants, Olivia is the perfect example of a girlboss: a woman who achieves success by upholding existing structures. She will continue to treat others as resources, as shown by her uncomfortable use of the possessive —“our Osmans”— for her own gain. And who can say whether she believes any of her virtuous proclamations, as Ruthnum colours his character (who is in her late twenties) with enough earnestness to keep us guessing. The only thing Olivia doesn’t do is cry.

Tajja Isen’s debut collection of essays, Some of My Best Friends, is similarly concerned with the disconnects between language and intention, and between intention and action. In the titular essay, she takes on the girlboss trope, particularly its roots in white feminism: that “awkward tension” that exists for those who “are marginalized by virtue of their gender but insulated by racial privilege.” Here Isen notes the weaponization of tears and apologies —“if that’s what they are”— as numerous talks, memes, and think pieces have made an industry out of privilege checks and promises to listen. But these often very public performances, like Olivia’s address, “haven’t diminished white women’s ability to accrue power.” Instead, their gestures “blur the line between contrition for past wrongs and the expectation that they’ll be rewarded for admitting them.”

At the core of Some of My Best Friends is an interrogation of “lip service,” defined here as the “bait and switch” of pulling “our attention away from foundational cracks to point toward something prettier out the window.” Take, for instance, how the concept of anti-racism has been diluted from “actively opposing violence” to “being nice and buying stuff.” Isen acknowledges that “sometimes these misguided acts and actors truly are sincere,” but she also holds in her mind an “implicit reminder that a well-meaning gesture might be all talk.” While these essays cover a wide range of topics — her experiences as a young Black voice actor during the “authenticity boom” in the early 2000s, the whiteness of the literary canon, and legal precedents for diversity — there is a common and insistent focus on hypocrisy.

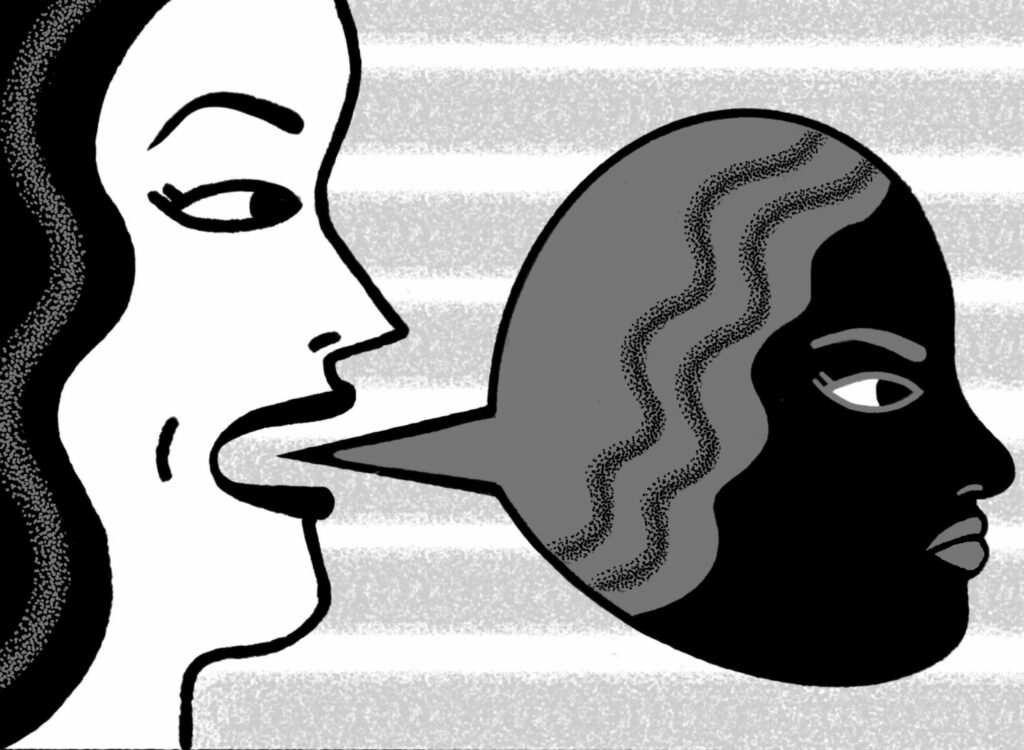

Lip service and other rhetorical moves.

Jamie Bennett

In “Diversity Hire,” Isen builds on the scholar Sara Ahmed’s dissection of non-performative language in On Being Included, from 2012. In Ahmed’s words, the “failure of the speech act to do what it says is not a failure of intent or even circumstance”; instead, failure is what the speech is actually doing. It’s an avoidance tactic “like I’ll call you or let’s do lunch or the check is in the mail,” Isen comments. The corporate diversity statement, the legal statement of principles, and the trend toward authentic voices in writing and voice acting may always have been intended to replace the diversity work that they beckon.

Although the collection is deeply concerned with the ethics of intention, there is no tone of moral purity here. Isen is playful with language, deploying a pithiness that is biting and humorous and that continuously probes meaning. In “This Time It’s Personal,” she notes the essayist Lauren Oyler’s observation that “necessary” has become a critical descriptor; Oyler comments on the “dully predictable tendency to throw the word at artists from marginalized backgrounds.” But a few pages later Isen refers to the kind of work white feminism does as “good and necessary.” In such moments, it almost feels as if she is winking at readers.

So too “Some of My Best Friends” inverts that well-worn denial of racism as a defence against Isen’s wider critique of “white femininity”: “I love white women,” she writes, “they are, truly, some of my best friends.” As she weighs the progress made against the work that still remains, she never loses sight of the comedy behind the “theater of good intentions,” what she calls the “thousand little laughs on the road to hell.”

A Hero of Our Time, takes a similar approach to Isen’s “thousand little laughs.” Ruthnum previously published Curry: Eating, Reading, and Race, in 2017, a long-form essay that questioned why a dish that “isn’t real,” that is “a leaf, a process, a certain kind of gravy,” has become such a cultural catch‑all. He has also put out two crime thrillers, most recently Your Life Is Mine, under the pen name Nathan Ripley. Although his latest novel avoids outright murder, it is still a story of deception and hidden identities.

Osman, the man at the centre of Olivia’s lip service, sees that her grand speech — which references AAP’s “perfect diversity statistics”— is not designed to disrupt the status quo. As a result, he embarks on his own scheme to expose her, digging into her relationships and her past, and enlisting the help of two co-workers, Nena and Vikram. But Osman is no straightforward hero, and this is no straightforward morality tale.

A pitiable figure, he is consumed with self-loathing. He obsesses over Nena, his only friend, to the extent that he keeps a photo of a bruise she gave him (as proof that she once touched him) and, at one point, uses clear tape to lift her fingerprint off his bookshelf. But Osman is also deeply self-aware, recognizing his own culpability when he says that “anyone who takes pleasure in rendering even brief power from goodwill and fear is shit.”

Other characters in the novel also experiment with self-creation, a pursuit that blurs the line between being used by the system and using it themselves. Nena, with all of her confidence and bravado, renames herself “Nena Zadeh-Brot” because it sounds “old world and pan-cultural and unplaceable.” Vikram Chandra, a “third-generation Californian” and VP at the company, “had broken his spine doing a skateboard trick” but “had allowed an undetailed childhood slum disease rumour to spread.” The narrator’s own father wants his son to write “deliberately false” memoirs on his behalf, to incite interest in his academic work by giving a broader audience “a story that they’ll like to hear.” Even as Osman charts the willingness of those around him to mould themselves to suit expectations and offer a kind of trauma porn, he accepts that Olivia thinks he is from Pakistan and Muslim (despite his protestations that his ethnic background is Indian and that he’s an atheist). He decides that if she were to ask him again, he “would extend a tortured salaam alaikum” and tell her to not let others know until he is ready.

Although Osman Shah is preoccupied with peering behind the facades of his peers, his concerns differ from those expressed in Some of My Best Friends. His objective is more complicated than merely exposing hypocrisy; instead, he’s interested in discovery, in recognizing the power of language and stories, just as Ruthnum is interested in exploring the interplay between cynicism and sincerity. While each book raises a skeptical eyebrow at the rhetoric of diversity, especially within the bell jar of the corporate world, A Hero of Our Time does not denounce its characters’ behaviour. It is all part of the absurdity of trying to fit an individual into a uniform collective. What is there to do but laugh?

.