Eric Reguly, the Globe and Mail’s European bureau chief since 2014, grew up in a newspapering family. So did I. Our fathers had the good fortune to work in print journalism during its heyday in the 1950s and ’60s, when papers turned a handsome profit and newsrooms teemed with reporters, most of them male and the best of them whip-smart and hyper-competitive.

My father worked on the nuts-and-bolts side of newspapering, as the publisher of small-market dailies in southern Ontario. He was good at his job but harboured a barely concealed jealousy of the reporters he employed. They had all the fun, got all the glory. The Graflex Speed Graphic press camera he kept in the family car bore witness to his hankering to get in on the action.

It was in the pages of the Toronto Star that my father’s spurned inner newshound found solace. Every evening after dinner, he would crack open the paper and read every word of it — as if it were a reward for his day of crunching numbers and facing off against the typographers’ union.

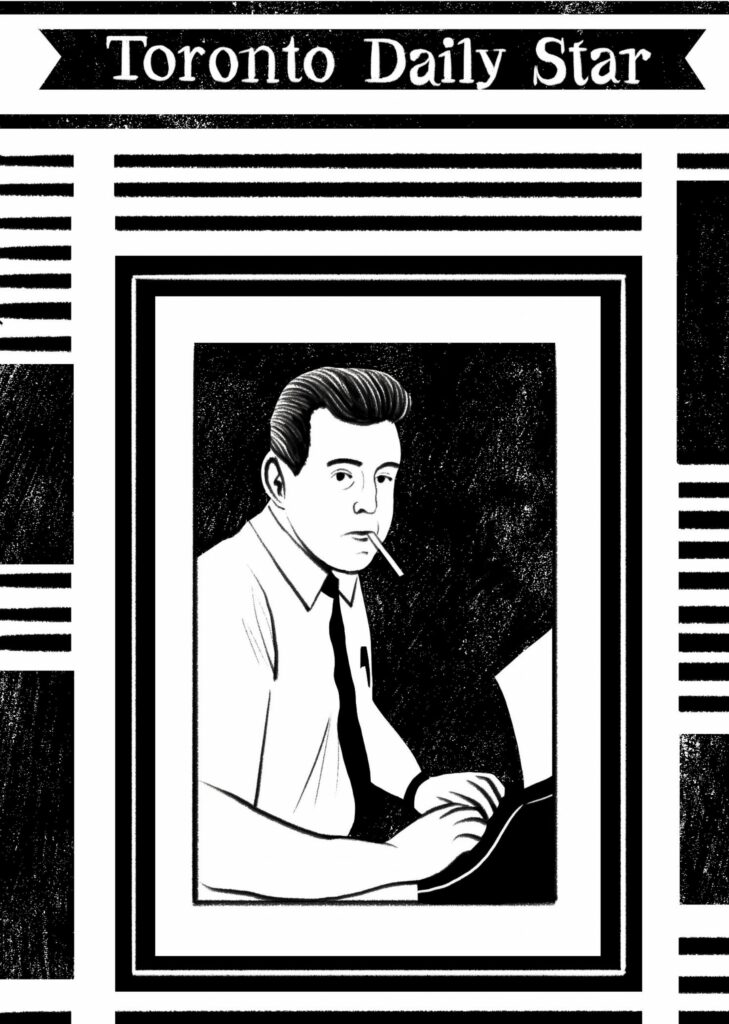

The portrait of a foreign correspondent.

Chloe Cushman

His habit followed him to the grave. The eulogy at his funeral included a quip about eternity being a subscription to the Star that never expired. If there were such a thing as reincarnation, I’m pretty sure he’d choose to come back as a “Star man”— the label the headline writers in Toronto reserved for select reporters whose ingenuity and derring‑do produced the scoops the paper coveted.

Eric Reguly’s father, Robert Reguly, was the heavyweight champion of Star men. He won the title in the mid-’60s, tracking down the fugitive mobster Hal Banks and, a couple of years later, Gerda Munsinger, the East German spy who was at the centre of an Ottawa sex scandal but had been presumed dead. Both scoops earned him National Newspaper Awards as well as a plum posting as the Star ’s Washington bureau chief, in 1966. From there he branched out to cover the biggest story of the day, America’s war in Vietnam.

Ghosts of War grew out of a 2018 Globe and Mail piece Eric Reguly wrote about his quest to retrace his father’s reporting sorties throughout Southeast Asia, “to learn more about how he covered the war, what motivated him, and how it changed him.” The armed conflict remains the core of the book, but around it Reguly has constructed a candid, riveting story of a son’s efforts to understand a father and mentor he admired but only partly knew.

At 134 pages, this is a slim volume, yet it’s insightful, moving, and richly detailed. Reguly uses the first six chapters to map out his father’s path to becoming the pre-eminent Canadian journalist of his day. It’s a story of ambition and grit: a lonely Slovakian immigrants’ kid from a hardscrabble town in Northern Ontario discovers the joys of literature, gets himself educated, develops a lust for adventure, lands his first reporting jobs, and eventually makes it to Toronto and the country’s biggest daily in 1957.

“My father was a walking caricature of a newsman of his era,” Reguly writes. “One of my favourite photographs shows him at his typewriter, cigarette dangling from his lips, a cocky grin lighting up his face.” Robert’s cockiness in chasing down minor stories paid huge dividends when it came to the riskier big ones like the Banks and Munsinger scoops. “My mother says her husband certainly was brave,” Eric explains. “But she is also convinced that his brain’s neurocircuitry simply did not register fear like ordinary humans.”

Long after Robert’s newspaper days were over, his face would “light up like a candle” when he talked to his son about Vietnam. Although he came to detest the war as unwinnable and evil, he loved covering it — exulting in the “close calls, the adrenaline rushes, the adventure, the sheer freedom from the daily grind, the journeys into the unknown, living a millimetre, a nanosecond, from death.”

The Vietnam that Eric Reguly encountered proved to be vastly different from the country whose agony his father depicted in his dispatches for the Star. It had become an economic powerhouse, the skylines of its bustling cities studded with gleaming towers, hamlets that were once killing fields now transformed into subdivisions. Memories of the war itself are fading: Reguly struggled to find local witnesses to the clashes his father chronicled. The effort finally paid off when he stumbled upon an elderly Montagnard man who had likely crossed paths with Robert during an American infantry operation in June 1967. “I felt spiritually closer to him in those precious moments,” Reguly writes of his father, “than at any time since his death eight years earlier.”

The moment was especially poignant because, as Reguly tells it, Robert was a far better reporter than he was a dad. “He was always away. When he was home, he was absent too, obsessed with the next big story, buried in newspapers, drinking with contacts, largely oblivious to the needs of his stressed-out wife and three young kids.”

Eric Reguly’s trip to Ho Chi Minh City and beyond was partly a waypoint on a son’s journey of forgiveness. It was also partly about atonement. He confesses to being haunted by a hurtful jab he uttered in the wake of a libel lawsuit that ended his father’s newspaper career in 1981. The offhand remark — just two words — still makes him “wince with pain and regret.”

After his year in Vietnam, Robert went on to cover wars in Bangladesh, Biafra, and the Middle East as well as major stories closer to home, including the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, which he witnessed first-hand in 1968. But as far as his son is concerned, Vietnam was where his career peaked. The younger Reguly ended his visit to the country frustrated that he hadn’t been fully able to accomplish his mission. But maybe that was apt. Coming to grips with the ghost of a larger-than-life parent, as well as the complexities of oneself, is work that is rarely finished.

Speaking of ghosts, Reguly’s book about his father stirred memories of my own. My dad would have loved this book; I could see him scarfing it down in a single sitting. I could also imagine it tweaking the part of him that yearned for the adventurous side of newspapering. He died with that longing unfulfilled. But I want to believe that before he passed on, he found comfort in the assurance that you don’t have to be a Star man to be a good man.

David Wilson edited The United Church Observer from 2006 to 2017.