If you own a bike in a city, you know you’re tempting fate when you leave it unattended for a minute without locking it securely. So when you consider the value of all that wood standing unguarded in the wild, it’s no surprise that clandestine loggers are preying on it throughout the United States and Canada. What’s more, these North American tree thieves are a tiny group compared with those in the developing world, where the poverty of displaced populations makes taking unharvested timber an even greater temptation.

With Tree Thieves: Crime and Survival in North America’s Woods, Lyndsie Bourgon, whose work has appeared in The Atlantic, Smithsonian, and National Geographic, places lumber poaching into context, including the deindustrialization of the working class and long-standing urban-rural divides. She does much of that by focusing on the redwood forests of northern California and the small community of Orick.

Once home to 2,000 inhabitants and four sawmills but now barely hanging on, Orick provides a case study of how environmental preservation efforts can affect a place that is dependent on resource extraction. In the 1920s and ’30s, California established three state parks north of the town to protect old-growth sequoias. Then in 1968, the federal government created Redwood National Park on Orick’s doorstep. Two years later, a proposed expansion to the park threatened some 1,300 jobs, in the town and throughout the wider Humboldt County area. The following decade, moves to protect the northern spotted owl resulted in another round of job losses, this time across the West Coast.

The hospitality industry has been a poor economic substitute for the lost logging. “While more than 400,000 tourists were estimated to visit the Redwoods parks each year in the late 1970s,” Bourgon writes, “many of them drove straight through towns such as Orick without stopping; instead they parked their cars at Redwood Highway pull-off points and trailheads for short hikes.”

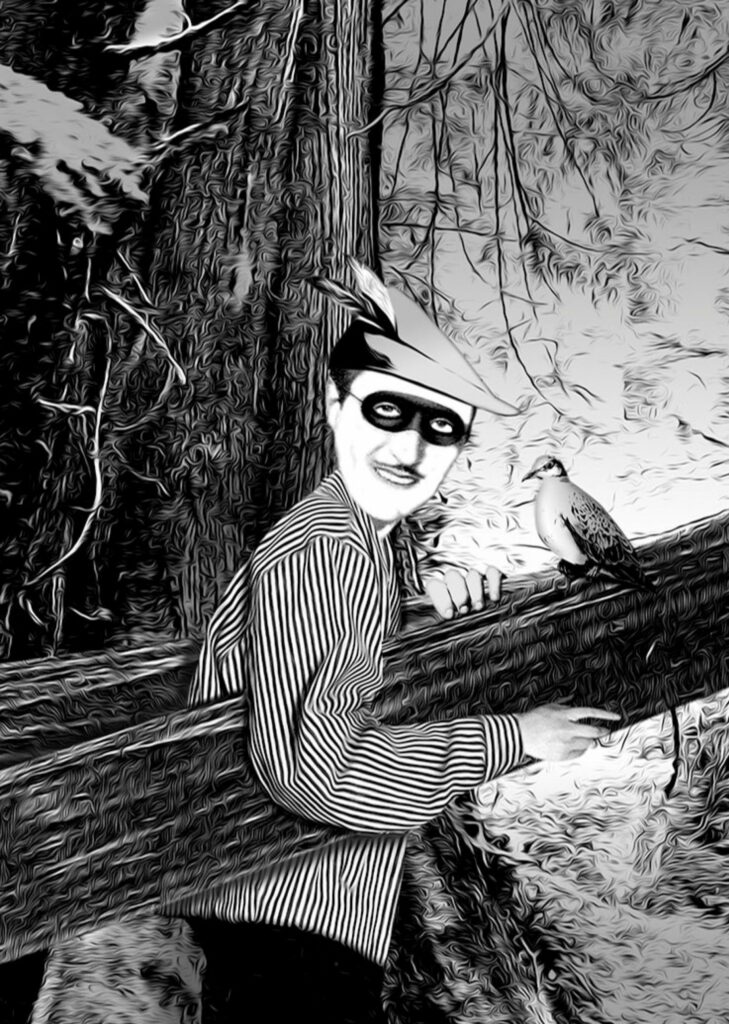

Like the heirs of an iconic figure.

Pierre-Paul Pariseau

Bourgon notes that environmental movements are often led by university-educated city dwellers, who reap the benefits of outdoor recreation but don’t experience the economic and social decline first-hand. The resulting conflicts carry a strong whiff of class disdain from the preservationists and of resentment from those on the ground. The book includes several examples of the elite attitudes that fuel bitterness in logging country. The prominent activist Judi Bari, for instance, once “belied her supposed sympathy for the local community of working-class loggers” at a demonstration organized by Earth First!, an influential activist group. “There’s too much inbreeding too,” Bari said of California’s North Coast. “It’s a rural area. The genetic pool is not large, and some of these families have lived here for five generations.”

With legitimate work in the forests disappearing, some Orick residents turned to tree poaching, a crime that seems easy to get away with, given the immense size of the woodlands and the difficulty of proving that a certain load of lumber originated in a protected area. Often those thieves don’t steal full redwoods but rather burls, large growths that are coveted for their distinctive grains. Sometimes they take burls from standing trees or from the stumps of cut ones. They also harvest planks from logs that have washed up on the beach, a once common practice now forbidden in order to protect nesting habitats for the endangered western snowy plover. (Further up the coast in Washington, some go after a type of maple tree that is especially prized for making musical instruments; a specimen with the right grain pattern can be worth $10,000.)

To many residents of Orick, lumber poaching represents a legitimate act of resistance against the encroachment of far-off governments. In this, they are echoed by some residents of forestry towns in Bourgon’s home province of British Columbia. It’s clear, though, that fencing off a watershed here or there has merely accelerated the inevitable end to an industry that has been effectively strip-mining its own future for decades. “Between 1850 and 1990,” she writes, “96 percent of redwoods disappeared due to logging.”

After introducing the main players in Orick and the National Park Service, Bourgon follows a years-long game of cat and mouse between park rangers and illegal harvesters. It’s a game that has become increasingly high-tech. DNA sequencing, for instance, has provided prosecutors with a way to prove that suspect material came from protected stands. Bourgon visits a forensics lab in Oregon that once showed how the guitar maker Gibson was using illegally cut Madagascar rosewood; the company was fined $300,000 in 2012 for doing so.

While she doesn’t condone their activities, Bourgon writes with sympathy for the poachers. “So why might someone steal a tree?” she asks. “For money, yes. But also for a sense of control, for family, for ownership, for products that you and I have in our homes, for drugs. I have begun to see the act of timber poaching as not simply a dramatic environmental crime, but something deeper — an act to reclaim one’s place in a rapidly changing world, a deed of necessity.”

Reaching way back, Bourgon suggests a parallel between the growth of national parks and other protected areas in the past century and the creation of forests as exclusive hunting preserves for medieval nobility. In order to ensure a steady supply of game, William the Conqueror and his heirs appropriated lands from those who had previously taken advantage of them to gather food, fuel, and building materials. In the early thirteenth century, King John affirmed the rights of Englishmen to use forests in their traditional ways, but these rights and resources were gradually lost to the gentry. Such a lineage suggests that the supposedly inbred outlaws of modern Humboldt County are the heirs of an iconic literary figure. “Whereas the story of Robin Hood has him dodging the Sheriff of Nottingham,” Bourgon writes, “in reality he most likely would have been slipping the grasp of a gamekeeper.”

Sympathetic though she may be, Bourgon is clear on the scale of the problem, which becomes especially daunting when she visits the Peruvian Amazon. Near the town of Infierno, in the region of Madre de Dios, an Indigenous community manages 6,000 hectares of rainforest both for environmental preservation and for economic opportunity. But it lacks the ability to keep out thieves, even from a relatively tiny parcel of land in the vastness of the Amazon basin. Considering that a single specimen of a prized ironwood is worth $775 (U.S.), poaching offers a much-needed income for poor Peruvians, including the hundreds of new residents drawn each day to the nearby city of Puerto Maldonado: “Regions like Madre de Dios are now swamped with people striving to make a living, looking for anything that might pay the bills, and seeking out a place to live. Every morning on the streets of Puerto Maldonado, men line up hoping to be picked for daily logging jobs. Often they are hired and sent somewhere to fell trees illegally.”

While the law-breaking loggers near Orick are relatively small-time criminals — selling burls for a few hundred bucks — the scale of loss is far greater when big businesses get involved, often with government collusion. Bourgon explains that 30 percent of the global wood trade is illegal and that “an estimated 80 percent of all Amazonian wood harvested today is poached.”

The community forest that Bourgon visits in Peru is meant to model a promising management regime. The idea is that locals oversee their own resources with preservation, recreation, and extraction in mind, which incentivizes them to operate sustainably and to protect the ecosystem for the future. The poaching she witnesses on her trip, however, suggests that poverty can pose a challenge too great for a small management group. For that matter, Bourgon learns that a community forest on British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast lost at least 1,000 trees to illegal activities last decade.

It’s somewhat puzzling, then, that in a short concluding chapter, Bourgon seems to place so much faith in the potential of community forests to convert the outlaw loggers of Orick (and others like them) into green defenders. A greater emphasis on local resource management, she suggests, would allow us to change our approach to conservation, with less emphasis on preserving large areas that are patrolled by police-style rangers. “Some community forests in Mexico are so successful that experts have proposed them as a global model,” she writes. Unfortunately, she didn’t visit Mexico for her book, and media accounts paint a sobering picture of illicit logging there, in some cases by drug cartels diversifying their income stream.

Tree Thieves is a fascinating true-crime story and a well reported examination of how a global problem has revealed itself in a few forests throughout California, British Columbia, and Peru. But — perhaps because the coronavirus cut the author’s research travels short — it doesn’t offer convincing support for the prescriptive note on which it ends. A post-pandemic second edition could allow Bourgon to flesh out her hopeful ending.

Bob Armstrong is the author of Prodigies, an award-winning Western, and, since 2002, the speech writer for Manitoba’s lieutenant-governor.