After I first met Jack Diamond, more than forty years ago now, I thought of Howard Roark, the architect protagonist of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. Diamond didn’t look like Gary Cooper, who played Roark in the 1949 adaptation of the novel, but he was charismatic and he believed, like Rand’s character, that architects could help create a better world — that they could be more than mere functionaries of commerce.

If Context & Content, Diamond’s new memoir, were ever made into a movie, I’d suggest Benedict Cumberbatch for the lead. He could pull off the daunting combination of sexy rugby boy from the wilds of Africa who goes to Oxford, the young man lucky enough to work in important firms, the sketcher and watercolourist, the academic, music lover, magazine editor, social commentator, father, and grandfather, the crusader for better cities, and the internationally famous architect.

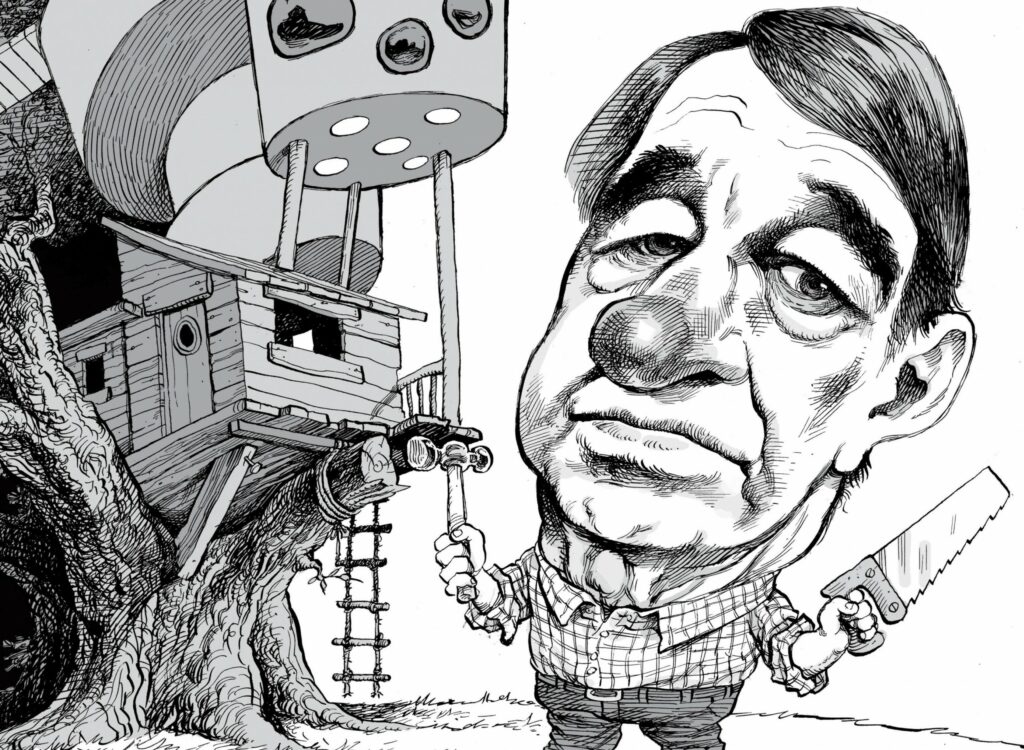

From tree house to beyond.

David Parkins

I joined Diamond’s office on a contract a couple of years after I earned an architecture degree from the University of Toronto. For a few months, I erased drawings — or at least parts of them — of a housing project, the exterior cladding of which was being modified to reduce costs. Each morning, I’d arrive to blueprints on my desk with instructions as to which walls, or whatever, were to be removed from the Mylar originals. I’d then use my electric eraser to wipe out the lines, taking breaks only to brush the mountain of eraser shreds off my lap. It wasn’t glamorous work, and I didn’t last much longer in the business. But it’s fascinating to read about those who did stick it out and to better understand their innate desire to create.

Diamond comments on this desire in his prologue. He vividly recalls his childhood tree house —“the first house of my own making”— built when he was just nine. “The satisfaction I felt at this accomplishment has stayed with me,” he writes, as has “the exaltation of first imagining and then creating.” What he has been imagining and creating ever since is a testament to both his talent and his determination.

After poetically describing that promising beginning, Diamond leaps ahead six decades, to his early work on the high-profile commission for the Mariinsky Theatre second stage, in St. Petersburg, Russia. His involvement began in December 2007 at a dinner in Toronto, where he met and chatted late into the evening with the formidable Russian conductor Valery Gergiev.

Gergiev was in town with the Mariinsky Orchestra, which was playing a Stravinsky program at Roy Thomson Hall. He had recently taken a tour of Diamond’s Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, just a couple of blocks away, and admired what he had seen: a facility with exceptional acoustics and modest construction costs. Six months later, Diamond was in New York, where Gergiev showed him the French postmodernist Dominique Perrault’s designs for a new Russian opera house in the Mariinsky complex: a huge theatre, with many stages, rehearsal halls, and production facilities, to be built on a gem of a site. Diamond was not impressed. “It already had a troubled, complex history worthy of Kafka,” he writes of the project, “and I would soon find myself part of the story.”

In November 2008, Vladimir Putin cancelled Perrault’s costly plan, and after a new design competition, Diamond was selected to, as he puts it, create a theatre that “would be both a harmonious aggregate to the city’s historic urbanity and be distinguished from it,” with a design that would “resolve seemingly irreconcilably opposing factors.” He explains how he achieved this aim with the building’s scale and materials as well as a stylistic connection to its extraordinary context. An inspired architectural concept doesn’t help you cope with a Byzantine bureaucracy, meddling politicians, and obvious corruption, however. Even having Gergiev in his corner — and with a widespread understanding that Putin supported Gergiev — didn’t make the process any less torturous.

The story of Mariinsky II careens from highs to lows, but Diamond’s plan was ultimately built, and in 2012 Gergiev hosted a dinner to thank Putin for his support. (“Appropriately,” Diamond writes, it was held “in the Czar’s dining room in the original opera house.”) After the architect made some remarks, Putin “generously thanked me for my contribution.” They would meet again at the gala opening, when the Russian president, who pretends he doesn’t know English well, spoke to Diamond directly, without an interpreter: “You know, Italian architects designed Saint Petersburg and the Kremlin; that is a state building like this new opera house. They did a good job, as you have done here. We did not let them leave the country.”

It’s difficult to imagine better, more riveting content. Having met Putin — not once but twice — is a tale to dine out on for years. Diamond’s account, however, reads almost like a business case study. You want to know how he felt meeting the former KGB officer? Did the Russian come across as reptilian, as some have suggested? Was he the “small, evil, feral-eyed man” that Mitt Romney once described? Diamond doesn’t say.

Stories related to Diamond’s other major commissions — like the Maison symphonique de Montréal, Jerusalem’s new city hall, or the Foreign Ministry of Israel — would surely have plenty of intrigue too. But reading about these and other projects is like chatting with the architect at a cocktail party, only to have him stay mum about what really happened.

Context & Content could have been more revealing without becoming a tell‑all confessional. For instance, Diamond vividly recalls numerous Jewish ancestors who are important to him, and he makes many references to the impact of being Jewish throughout his life. He describes “the material and the spiritual” as being “particularly Jewish characteristics” at one point: “When in dynamic balance, the accomplishments can be of great humanistic value. When one or the other is predominant, the result is crass materialism or empty ritual.” He also explains how his wife, Gillian, converted to Judaism, admittedly “more for family peace and acceptance than religious convictions.” So it comes as a shock to stumble on a sentence, almost out of the blue, where he states he’s an atheist. No further explanation. Similarly, he alludes to prestigious job offers that appeared and that he rejected. Did Diamond apply for these positions? Was he sought out? What about all those other opportunities that arose, seemingly without guile on his part?

Perhaps there’s something about memoir — unlike autobiography, which often tries to be explicit and thorough and chronological — that invites authors to simply omit what they don’t want to reminisce about. Consider the one paragraph Diamond includes about Barton Myers, his former associate. He recounts how, in the late 1960s, he invited Myers to Toronto from Philadelphia, made him a partner, and changed his firm’s name to Diamond and Myers. Many believed it was the most dynamic partnership in the country for a time. Then “there was both a clash of egos and a difference in philosophy.”

Given a choice, who wants to rehash unpleasantness and make explicit comments rather than repeat the euphemistic lines about difficult junctures that one has practised for years? Again, the nature of memoir allows a writer to minimize such awkward situations, and Diamond takes full advantage. At least he does conclude with a little poke, writing, “Myers valued technology, and designed a steel house on stilts that was spectacularly unsuited to Toronto’s climate. It was a triumph of aesthetic over purpose.” There must be so much more to the story! Besides, which good architect doesn’t have an aesthetic preference that supersedes a practical consideration?

Diamond also sidesteps, more or less, his personal life outside the office. He mentions meeting Gillian at Oxford and includes some descriptions of their newlywed years, along with the births of their two children. That is about as much as the reader gets, though, other than some black and white family photographs. (But what we really want is pictures of Diamond’s buildings.) Isn’t it better to leave something out entirely than to tease? If an architect is going to refer to his private life at all, maybe he could explain how his personal experiences influenced his creative process. Even in his acknowledgements, Diamond’s choice of language inadvertently titillates: “I owe the greatest debt of all to the forbearance and encouragement of my wife, Gillian. Without her love, devotion, and tolerance, none of my achievements would have been possible.”

In other matters, Diamond doesn’t lack for strong opinions, and his forceful voice comes through when he discusses architectural competitions, including a few that he didn’t win. He doesn’t sound like Donald Trump — rambling on and on about something he lost. Rather, he makes intelligent points about how competitions rarely produce the most appropriate solutions. His passion here makes other memories seem rather tepid by comparison. Diamond is known for his bravado, which surfaces occasionally throughout the book, peppered as it is with proof of his stellar intellect and significant erudition. But, like many of his elegant buildings, Diamond’s self-presentation in Context & Content is largely subdued.

When I worked for Jack Diamond all those years ago, I was excited to be there. At the time, his office — like those of Barton Myers, Eb Zeidler, and maybe Ron Thom — was the top of the heap in Toronto. (Yes, Arthur Erickson was around, but his practice was still mostly in Vancouver.) The work of these firms endures, particularly Diamond’s early oeuvre. Time has made the reasonable, civic-minded intent behind those buildings clearer: modernism with a touch of Louis Kahn finesse. They remain a welcome relief from the attention-seeking creations of one star architect after another.

Even with its omissions, it’s almost impossible to read Context & Content and not enjoy it, especially if you admire the landmarks its author has managed to force into existence against great odds. (Or if you started down the architectural path but, like me, didn’t get past the first obstacle or that electric eraser.) Diamond speaks of the contradictions that must be resolved to create a suitable structure. Perhaps the same can be said of writing about one’s own remarkable life and career. Indeed, Complexity & Contradiction probably would have made a more apt title for this book — but Robert Venturi got there first.

Kelvin Browne wishes Savannah weren’t in the United States — so that he could visit again.