According to a recent version of the CBC’s language guide, “there is no modern country of Palestine,” and journalists working for the Mother Corp should “not refer to Palestine or show a map with Palestine as a country.” So when the contenders for the 2021 CBC Short Story Prize were announced, it was refreshing to see among them a work that acknowledged that very place, “Her First Palestinian.”

With the publication of his debut collection, also called Her First Palestinian, the author and lawyer Saeed Teebi arrives as a startling new voice. Consisting of nine stories, all of which concern Palestinian characters living in Canada, the book is riveting, significant, and sure to make waves in literary circles. Regarding a people so thoroughly marginalized in the cultural discourse, it is a powerful rebuke to those who wish the Palestinian narrative would stay out of sight and mind.

For years, Palestinian American writers such as Randa Jarrar and Susan Abulhawa have found audiences and acclaim south of the border, while readers of Canadian fiction have had more limited access to the Palestinian experience. An outlier is I Am Ariel Sharon, a poetic, devastating accounting of the former Israeli prime minister, written by the Québécois Palestinian author Yara El-Ghadban and translated from the French by Wayne Grady (notably, also published by House of Anansi Press, in 2020). Increasingly, though, social media and amplified activism are drawing attention to the situation in Gaza, the West Bank, and Israel itself. The tide is changing, and our literature will inevitably respond. In this context, Teebi is at the edge of the wave: taking serious risks, creating complex, three-dimensional characters, and pushing the world of Canadian letters to its limits.

The stories in Her First Palestinian are clear about the historical reality of Israeli violence. Yet victimhood does not overwhelm their day-to-day narratives. These are not tales of suffering; there is no trauma porn here. Teebi’s characters have all, for the most part, achieved diasporic success. Whether they’re lawyers, doctors, or math professors, they have family, homes, community, and pride. Nonetheless, their experiences reveal the constant tension of living in a hostile world. The writing is direct, confessional (six stories are in the first person), and capacious enough to encompass both “little droplets of human drama” and the geopolitics that consumes those droplets like a vast, unfathomable ocean.

Teebi writes right up against the present moment (some of the plot lines touch on Black Lives Matter and COVID-19) and captures the persistent challenges of life in a modern diaspora. In “Do Not Write about the King,” the mathematician Murad observes on his personal blog, “Interestingly, this same graph is used by the King of ______ to determine hiding spots for the body parts of his critics.” In doing so, the professor instigates a family crisis. Even though only a handful of people read the online post, it bothers Murad’s father, who was a refugee in the unnamed kingdom and started his family there before moving to Mississauga, Ontario, where he reigns as the “grand sultan of the corner of Mavis and Burnhamthorpe.” Elderly and dying, he urges his son to take the remarks down, fearing they will catch the kingdom’s attention. But Murad won’t budge: “No matter how hard my father was trying to force his fear on me, that was an inheritance in which I wanted no part.”

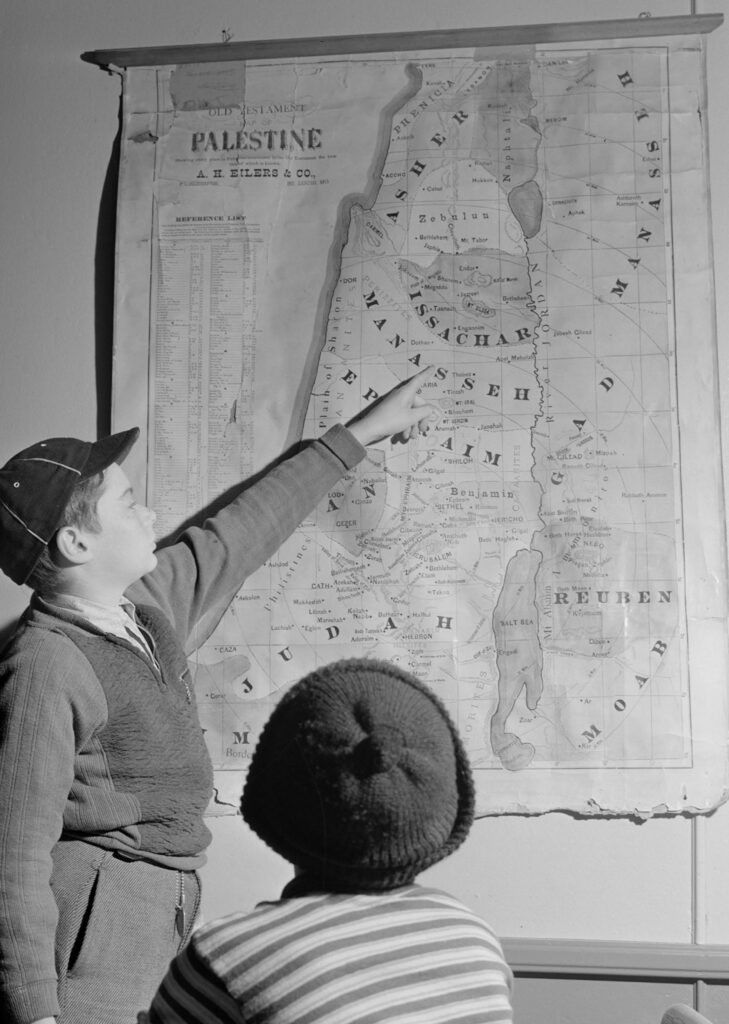

It’s right there on the map.

Jack Delano, 1940; Library of Congress

What at first seems like a story of a father overreacting veers darker when it turns out that, perhaps, somebody from the kingdom has seen the blog. When you’re Palestinian — at the mercy of host countries, unable to properly speak up against the nation-state that forced you out in the first place — what you say carries real weight. That Teebi himself omits the name of the kingdom furthers the story’s trenchant irony.

In the title story, after Abed teaches his white girlfriend, Nadia, about Palestine, she becomes obsessed with the cause and ends up leaving him for someone living in the West Bank. Evocatively, it asks who is “more” Palestinian: the one who lives comfortably in the diaspora or the one who suffers in the homeland? Meanwhile, in “Woodland,” Teebi takes aim at another example of settler colonialism, with a tale set partly in Ontario’s cottage country. Involving a fake Norval Morrisseau painting and estate sales as a metaphor for what we leave behind, the story successfully breaks apart the kind of historical compartmentalization that allows the oppression of Indigenous peoples to continue in Canada, much as it functions in the Middle East. Teebi himself nods to this parallel on his acknowledgements page: “These stories engage a people who have been violently and unjustly dispossessed of their land. I wrote them while living on the land of other people who were also violently and unjustly dispossessed.”

The collection’s final offering, “Enjoy Your Life, Capo,” underlines its major conceit. When Salah, a computer programmer, develops an app that can track the unique breathing pattern of every human being on the planet, it’s intended for medical application — specifically, to ease the suffering of his daughter, who has cystic fibrosis. However, it turns out the only interested buyer for the software is the Israeli military. As Salah agonizes over what to do, his daughter gets in trouble at school for posting pro-Palestinian messages on social media. This is the most haunting story in the book, with its intersecting themes of what it means to collaborate, the obligations of family, and the nefarious uses of technology, all of them corrupted by the influence of money — an eternal concern that Teebi uses here to bruising effect.

Her First Palestinian is a layered, fully imagined work of fiction: probing, sure of itself, astounded by life’s cruelties and surprising joys and by its ironies large and small. Salah, the programmer, poses the question at its heart: “There have to be limits to this warfare against us, no?” The book’s answer is a resounding, heartbreaking no. Although some readers will inevitably take issue with Teebi’s stance, he should be commended for not turning away, as should his publisher for issuing this unvarnished addition to the fictional — and historical — record. With these glimpses of Palestinians living in a world bent against them, the terrain of Canadian literature has slightly fewer walls, guard towers, and checkpoints.

Aaron Kreuter is the author of Shifting Baseline Syndrome, which was shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award for Poetry in 2022.