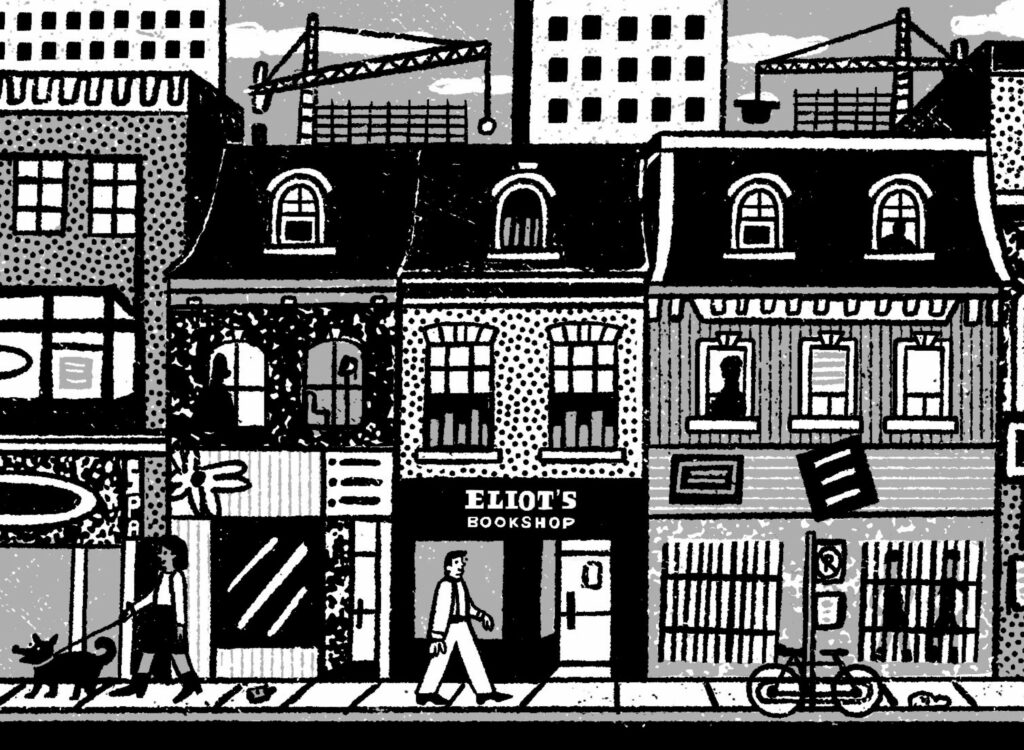

In the third movement of André Forget’s In the City of Pigs, a young music journalist named Alexander Otkazov takes a walk up Toronto’s Yonge Street to look for a second-hand copy of Goethe’s Faust in Eliot’s Bookshop, which is run by a churlish “dyspeptic Frenchman” with the best of literary intentions (Alex once saw the man turn his nose up at a box of Harry Potter books that a couple from the suburbs tried to sell to him). For the protagonist, the low walls crammed with volumes offer an aesthete’s refuge from “the foundation pits and fluorescent pharmacies” that have scarred the cityscape.

As Alex browses, he reflects on his literary education and casually mentions (to the reader) that the one writer he never tires of is Balzac: “all that sex and scheming.” His affection for La comédie humaine is not a question of intellectual stimulation: “If I was going to spend the evening reading a book,” he says, “I expected to be entertained.” But as he approaches the counter to pay, the owner begins to interrogate him: “Did you get an urge for edification?” Self-conscious about how well he can keep up with the Frenchman’s erudition, Alex explains he’s “just interested in the, uh, Faust legend itself. And the musical adaptations it’s inspired.” This precipitates a little lecture from the owner, after which Alex quietly submits to the latter’s better judgment.

It is a brief, vivid scene, and the nod to Balzac resonates with just the right touch of metafictional playfulness. Because what Forget has done with this, his first novel, is reinvigorate the kind of Bildungsroman made famous by Balzac’s Lost Illusions and Flaubert’s Sentimental Education. Such works chart the path from innocence to experience as the young rube takes on the big city and discovers all the sex and scheming — and indeed the realpolitik of money and influence that powers perpetual urban transformation, for good or ill. Alex discovers that, in twenty-first-century Toronto, cultural capital ultimately serves property values: art is but a bauble, a pearl before the swine of Hogtown.

There are strong parallels between the protagonist’s sentimental education and that of the author. After his school years in Winnipeg and Halifax, Forget moved to Canada’s largest city, where he edited a literary quarterly, The Puritan, and, much like Alex, dabbled in music journalism.* Throughout this time, Forget wrote some incisive book reviews and literary criticism. Most notably, “The Return of Political Fiction,” published in The Walrus in 2019, exposed the glaring contradictions and blind (unfortunately not colour-blind) spots in John Metcalf’s book The Canadian Short Story. After that, he edited and selected a collection of new fiction, aptly titled After Realism, which reads like a portfolio of formalistic dissent from the kind of stories Alex bemoans in In the City of Pigs, where “the main character would suddenly be reminded of their grandmother’s tea kettle and it would be over.” If such fiction has been so dominant in Canada, Forget contends, it is owing in no small measure to the influence of tastemakers like Metcalf.

A young music journalist strolls up a changing Yonge Street.

Sandi Falconer

In his opening essay, Forget observes that the kind of realism often associated with CanLit “seems inadequate for depicting the post-Trump, post-Brexit world. Gentle musings about love, time, memory, and death from financially comfortable Baby Boomers stick in the craw of a generation for whom paying rent is an increasingly difficult proposition.” Today’s hollowed-out publishing industry requires the young talented writer to be a “revenue machine”: a marketable commodity for long-term profit. The ecosystem of newspapers and magazines that once provided a reliable source of secondary income is rapidly disappearing, along with the critical conversation on literature.

Forget sees all these developments as galvanizing and politicizing the innovative drive among young authors. There is a new pluralization of ways of telling. Realism is no longer a dominant mode but one approach among many, and Canadian literature is shape-shifting in response to a broader range of influences than ever before.

One potent element of continuity in After Realism is the aim to “make strange” (as the Russian formalists like Viktor Shklovsky would put it) the well-trodden landscape of CanLit, with its signposts of epiphanies prompted by, as Otkazov points out, homely objects like a grandmother’s tea kettle. The tactics of defamiliarization in After Realism focus at the highest poetic resolution in a story like David Huebert’s “Chemical Valley,” which depicts a character’s vivid, dreamlike visualization of his own dissolution, “chopped into atoms, into confetti” that later blend “with the earth and the soil” of tainted farmland around Sarnia, Ontario. The strategy also works at a conceptual level in a story like Camilla Grudova’s “Madame Flora’s,” where young girls discover they can induce their periods through vampiric transactions with men from a neighbouring town. In their embrace of speculative fiction tropes, the stories in After Realism evince what A. S. Byatt once described as the “artifice, constraints and patterning” from which European storytelling “derives great energy.” Maybe it’s taken CanLit a little longer to develop this appreciation for such approaches, but they have found a passionate and eloquent champion in Forget.

The author’s critical sensibility is equally apparent in the formalistic approach he has taken with In the City of Pigs. “The novel,” Forget wrote in an opening letter to the readers of the advance copy, “is structured like a symphony: an expansive opening movement followed by three shorter movements, each with its own mood, tone, and subject.” At the level of the plot, he subtly transposes a critical dialogue on modernism and tradition from literature to music by making Alex Otkazov a failed composer who has turned to journalism as a last resort. The basic arc of the Bildungsroman is still there: it’s the theme in the major key. But a theme in a minor key also emerges when the artist’s quixotic obsession with creating a large-scale, innovative work collides with the demands of real estate capital, albeit with predictable results.

In the first movement, Alex returns to the world of classically inspired musical performance to get over his own creative failure. “The only chance I had of severing the psychic connection,” he reasons, “was to symbolically revisit the scene of my trauma by immersing myself in music again.” And so he decides to write about a mysterious experimental collective called Fera Civitatem that has become notorious for its anarchic, literally orgiastic performances in an old downtown theatre slated for demolition.

The catalyst figure who brings him into this milieu is a gifted, charismatic opera singer, Sev, who has taken work in the same restaurant as Alex. And though Alex thinks Sev is the most attractive man he’s ever seen —“a tall, muscular individual with brown skin and a pencil-thin moustache”— the character who truly initiates him into his trauma revisitation is a dark-haired woman who is “alarmingly, mathematically beautiful. Her cheekbones formed two exquisite scalene triangles united in sublime harmony by a delicately pointed chin.” This is Theresa Lykaios, a music journalist and woman of influence who has insider status among Fera Civitatem’s acolytes. She is also sexually involved with the person who turns out to be the novel’s shadowy antagonist: Sean Porter, patron of the arts and the man behind an “online marketplace app” that was shut down after the police discovered it was being used for drug trafficking and prostitution.

Throughout, Forget captures, in finely wrought detail, a louche milieu of trustafarians, tech bros, developers, and expensively educated libertines, all tenaciously hanging on to their cultural capital in Toronto (leading this reviewer to Google “Spoke Club still in business?”). But even the conversations Alex has with Sev, and then later with Theresa as our hero falls in lust with her, manage to be both portentous and pretentious in places. Their exchanges play out in a curious haute-Torontonian idiom, which mercifully warms to a tone less humourless and more emotionally direct in the latter sections of the novel.

In the last movement, Alex is seduced by an older woman who was once an up-and-coming opera singer, Margaret Standish. Her husband, Lionel, is a developer who moves among the patrician philanthropists and corporate directors with designs on the city’s future. Even though Margaret claims he has “a poet’s soul,” his projects have made the downtown streets increasingly unlivable for the artists who must toil in restaurants or, like Alex, pen fawning reviews for publications beholden to the monied class. It is the former singer’s reconciliation with the limitations of artistic ambition that leads Alex to a greater understanding of his own capacity for compromise. Appropriately, any spark of journalistic aspiration he might have had flickers out when the editor and publisher of the magazine who gave him work lets him go. This Lost Illusions theme plays out in major chords before Forget gives us a final contretemps between Otkazov and Porter, who has mastered the levers of power for ends that are bankrupt of any civic or ethical ideals. It is an effective finale.

Forget’s treatment of the minor theme, most prominent in the second and third movements, loses momentum somewhat. The frame of a realist novel has its constraints, and the dramatic energy of the opening movement is diffused when Alex travels to Halifax to research and write a profile of a huge musical organ constructed off the coast. Forget launches into a longueur that includes a discourse on the origins of this oddity. As the action returns to Toronto, the giant organ is left to resonate — and presumably marinate — as a metaphor for the folly of vaulting artistic ambition that overleaps itself. And later, in the third movement, the heavy hand of allegory looms as Alex descants on the performance considerations of the Faust-inspired opera that an old friend has composed and Lionel Standish has funded. Faustian bargains, deals with the devil: it is all laid on with a trowel when a little Goethean filigree would have sufficed.

Oddly, it is in Forget’s treatment of Lionel Standish and Sean Porter, the money men with less than noble designs for the city and its creatives, that the details seem most sketched in rather than fully realized. Whatever nefarious doings the two get up to, they happen in the shaded periphery of the main action. There’s a glimpse of something suggestive of Porter’s sadism in the opening movement, but he claims it’s all been “consensual, man.” Even Faust, regardless of the version, gives the devil his due. A little more of Mephistopheles would have only bolstered the case for Alex’s fall from innocence into something like enlightened failure.

Still, In the City of Pigs is an impressive debut novel, crafted with a deep understanding of the limitations of realism if also with impatience at those constraints that writers must accept in their role as “revenue machines.” Especially in the opening movement, Forget’s gift for the concise, waspish take on the mores of Toronto’s aspirational one-percenters has all the observational wit that was once found in the dailies and magazines (many of which have disappeared) that might have employed an Alex Otkazov.

Journalism’s loss is literature’s gain. Forget’s eye for aesthetic invention and his sharp critical sensibility as evidenced in After Realism bode well for greater things. Although In the City of Pigs did not make the short list for this year’s Giller Prize, the thought of Forget, at some point, seated among the milieu his novel’s character has so elegantly depicted evokes an irony worthy of Balzac.

* In print, this review incorrectly stated that Forget attended university in Montreal.

John Delacourt recently received a Pushcart Prize nomination for his story “Liner Notes.”

Related Letters and Responses

André Forget Kitchener, Ontario