Curiosity may have killed the cat, but it has also spawned legions of journalists. The prospect of learning something new every day by asking nosy questions, searching the internet for long-forgotten connections, and digging deep into the morgue — as the archives are known at most media outlets — gets us out of bed in the morning and often keeps us up long into the night. I loved even that most reviled of newspaper jobs — the dead beat — because writing obituaries offered variety and the chance to assess complicated lives in all their shades and lustres. Yes, there was escalating deadline pressure and editorial interference in direct proportion to the significance of my subject — Pierre Berton, Nelson Mandela, and, of course, the Queen come to mind — but that intensity was exhilarating, at least in retrospect. Besides, you never repeat yourself. There is no follow-up on an obituary.

I knew very little about the unheralded Holocaust hero Rudolf Vrba before I researched and wrote his obituary for the Globe and Mail in the spring of 2006, but I never forgot him. That’s one of the reasons I wanted to read Jonathan Freedland’s comprehensive book about the brilliant, uncompromising man who was born Walter Rosenberg in 1924, in what is now Slovakia, and who transformed himself into Rudolf Vrba, adopting this nom de guerre after his escape from Auschwitz in April 1944. Vrba and a fellow inmate, Alfred Wetzler, eluded German sentries and roll calls by hiding for three days in a makeshift bunker covered with timbers and cheap Soviet tobacco, drenched in petrol to dissuade sharp-nosed SS dogs. Knowing the Nazis patrolled only during daylight hours, the two men waited for darkness before they eased out of their hidey-hole and fled.

Getting away from the labour camp was daunting enough, but Vrba and Wetzler had a nobler purpose: to save the lives of other intended victims. To do that, they had to make their way through German lines in Poland to neighbouring Slovakia, contact the underground Jewish Council, and ask it to raise the alarm.

The baffling machinations involved in getting the message out are the underlying theme of The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World. In telling that tale, Freedland raises three disturbing questions. Why did the Allies not bomb the railway tracks leading to Auschwitz once they knew the truth about the Nazi slaughter of the Jews? Why didn’t the Jews, other than in the Warsaw ghetto, rebel en masse against their oppressors, instead of numbly climbing into the cattle cars at deportation stations? And why doesn’t Vrba fit the heroic mould of popular history? The answers are tangled — including our inherent unwillingness to accept the inevitability of our own deaths — but Freedland argues them cogently. We live in hope, often against insurmountable odds and in defiance of conclusive facts.

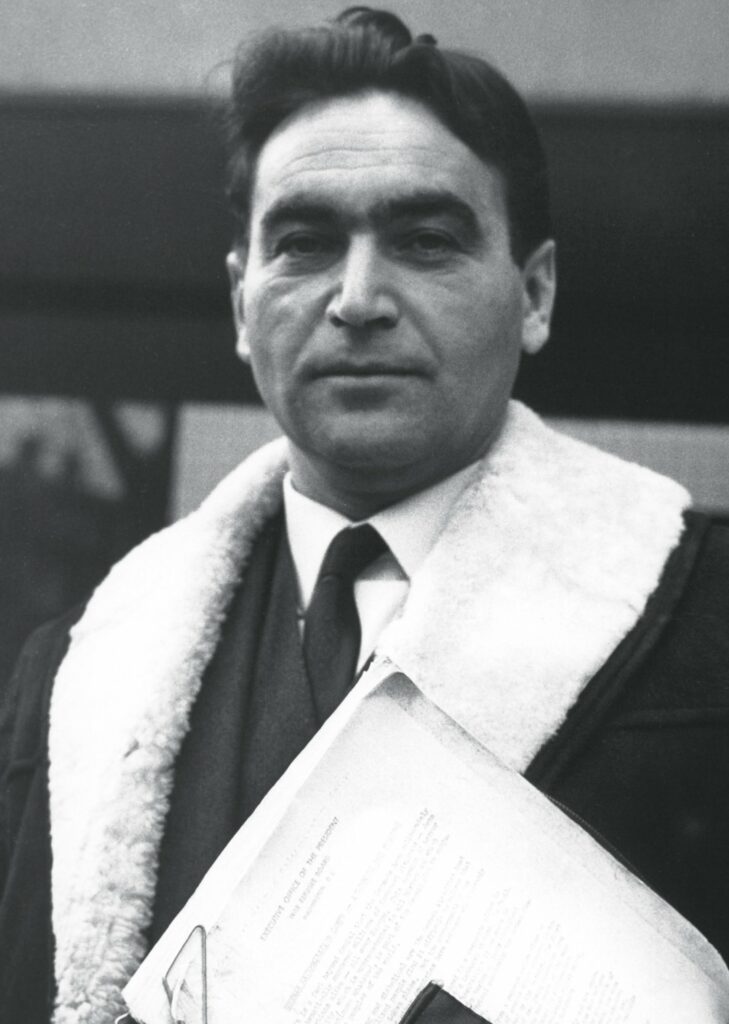

Arriving at the Frankfurt trials in late 1964.

Keystone Press; Alamy

One of four children of Elias Rosenberg and his wife, Ilona Rosenberg, Vrba was an able student, especially in chemistry. Fifteen when the Germans began their murderous march through Europe, he was expelled from high school under local antisemitic laws. He found work as a labourer until he was arrested in March 1942, deported to Poland where he was incarcerated in the concentration camp at Majdanek, and then transferred to Auschwitz.

He survived as prisoner 44070 for nearly two years, eventually working in Kanada, sorting the looted belongings of new arrivals. His task provided a vantage point to track and memorize the number of Jews coming in on transports and to calculate how many were forced into slave labour or sent to nearby Birkenau to be gassed. Early in 1944, after the Germans occupied Hungary, Vrba saw how the camp was being expanded to prepare for the arrival of huge numbers of Jews. He took that detailed information with him like precious cargo.

In accounts that came to be called the Auschwitz Protocols, Vrba and Wetzler bore accurate and detailed witness to the Jewish Council about the layout and function of gas chambers and crematoria, as well as the train tracks designed to transport Hungarian Jews directly to their deaths, bypassing the subterfuge of separating the able-bodied from those deemed too young, too old, or too frail to be useful as workers. After exhaustive interviews, the Jewish Council painstakingly produced typed transcripts and laboriously translated the cumbersome text into several European languages, including German, but not immediately into English.

Vrba grew frustrated when a general alert was not sounded. Instead, the Jewish Council debated and delayed and tried negotiating with Hitler’s henchman Adolf Eichmann. Meanwhile, the Hungarian Jews were lining up with their meagre belongings, and the trains kept speeding toward Auschwitz. Instead of bombing the tracks, the Allies pursued diplomacy as they played a larger end game, in which saving the Jews was not the primary goal.

The world has always been a complicated place, but it was especially so in Europe in the spring of 1944 as the Allies were finalizing plans for D-Day, hoping to crush the Axis powers. Finally, on July 2, 1944 — approximately three months after Vrba and Wetzler escaped from Auschwitz and four weeks after the Allied landings began in Normandy — American planes bombed Budapest. Within a week, the Hungarian admiral regent Miklós Horthy recognized that Germany was headed for defeat and halted the deportations.

Ultimately, Vrba’s desperate actions did save the lives of at least 150,000 Hungarian Jews, according to the British historian Sir Martin Gilbert’s Auschwitz and the Allies, but that wasn’t good enough. (Freedland, for his part, cites a figure of 200,000.) Vrba wanted to save them all, and for the rest of his life he railed against what he believed was the indifference of the Allies and the complicity of Jewish leaders in sacrificing the lives of many thousands to save themselves and their families.

After the war, Vrba gave evidence when Nazi collaborators were brought to trial, and he debunked the lies of such flagrant Holocaust deniers as Ernst Zündel, the notorious publisher and pamphleteer. But many saw Vrba as a troublesome character because he threatened the solidarity of the post-Holocaust Jewish community, especially in Israel, with his acidic recriminations, particularly in his 1963 memoir, I Cannot Forgive. Consequently, it was easier for many to ignore his heroism than to honour it.

That was the conclusion Freedland reached when he first learned about Vrba. In a note at the beginning of The Escape Artist, the British journalist recalls going to a London cinema in 1986 to watch Shoah, Claude Lanzmann’s magisterial nine-hour documentary, which features interviews with Vrba, among many other survivors, bystanders, and perpetrators of the Holocaust. Freedland was nineteen at the time, the same age as Vrba when he escaped from Auschwitz. And he was haunted by a question: Why had he, a Jew, never heard of Vrba? Why wasn’t Vrba’s name ranked alongside those of Anne Frank, Oskar Schindler, and Primo Levi?

It turns out that the answer had a lot to do with Vrba’s character and personality. In November 1978, Lanzmann interviewed him for nearly four hours in New York. Vrba, who was nattily dressed in a tan leather overcoat and who spoke in a central European accent, despite having lived in North America for a decade, was “a striking presence.” With “his thick dark hair and heavy eyebrows,” Freedland writes, “he could pass for Al Pacino in Scarface.” Vrba’s demeanour was unlike the solemnity of the other interviewees in Shoah. “Why do you smile so often when you talk about this?” Lanzmann asked him on camera. To which Vrba responded: “What should I do? Should I cry?”

Thirty years after first watching Shoah, and a decade after Vrba’s death from bladder cancer in Vancouver, Freedland found himself worried about the rise of “post-truth and fake news.” Then, sometime in 2016, he recalled “the man who had been ready to risk everything so that the world might know of a terrible truth hidden under a mountain of lies.”

Besides Gilbert, many other distinguished Holocaust scholars, including Michael Marrus and Robert Jan van Pelt, have written about Auschwitz. The Escape Artist is built on such work, but it is intended for a general audience. Freedland structures it around a biographical quest: to understand a moral absolutist whose uncompromising personality may have epitomized that cliché “his own worst enemy.” The book tracks Vrba’s life before and after the war, when he struggled to fit into the post-Holocaust community and his academic milieu, as well as his relationships with family and friends, including his fellow escapee, Fred Wetzler.

Freedland has done his homework, both in researching the voluminous historical accounts and in tracking down Vrba’s first wife, Gerta Vrbova, the mother of his two daughters, Helena and Zuza. He found her in Muswell Hill, London. After meeting in “the plague year of 2020,” they had long conversations in her garden about the “young man, then called Walter Rosenberg, and the world they had both known.”

Vrbova, who divorced Vrba in 1958 after ten years, eventually entrusted Freedland with “a red suitcase packed with Rudi’s letters, some telling of almost unbearable personal pain.” A few days after their last conversation, she died at the age of ninety-three. I hesitate to over-egg the symbolism, but it does strike me, having read Freedland’s account of the bitter vindictiveness that characterized the breakdown of the Vrba-Vrbova marriage, that she needed to unpack the story of that relationship before she could succumb to her own death.

After the war, Vrba pursued a series of degrees in chemistry, earning his doctorate in 1951. He did biochemical research at Charles University in Prague, lived in Israel for a couple of unhappy years, and, in the late 1960s, accepted a pharmacology appointment in the University of British Columbia’s faculty of medicine. While on sabbatical at Harvard Medical School in the mid-’70s, he met Robin Lipson, an American entrepreneur less than half his age. After they married in 1975, she became a successful real estate agent in Vancouver, providing him with financial and emotional security.

I remember phoning Robin Lipson when I was writing about her husband’s life seventeen years ago. She refused to speak to me, complaining that nobody was interested in him when he was alive so why should she talk about him now that he was dead. Grief causes people to behave in myriad ways, so I was glad to see that her intransigence had melted by the time Freedland contacted her for his book.

Lipson represented a younger postwar generation. Unlike Gerta Vrbova, she had no overt connection to the Holocaust. Also unlike Vrbova, she agreed to Vrba’s demand that they not have children, so he could be spared the devastating entanglements of fatherhood. According to Freedland, he told his second wife that his love for his daughters had made him vulnerable. He couldn’t risk that again, especially after the death of Helena, by suicide, in 1982. All his bluster, all his acerbic ferocity, all his refusal to adopt what he called “the survivor clichés manufactured for the taste of a certain type of public” was a shield to camouflage his fear and insecurity. That rigidity, that wariness, that vigilance had enabled him to escape Auschwitz, but he carried it with him for the rest of his life.

What are the personality traits that we demand in the heroes we celebrate? Why aren’t we prepared to accept more diversity? While Jonathan Freedland doesn’t resolve that conundrum, he does illuminate Rudolf Vrba’s tortured psyche and how “he could never fully break free from the horror he had witnessed and which he had laid bare before the world.” All of which refutes the old newspaper maxim that an obituary is the final word on somebody’s life. It stands only until an enterprising author writes a full-scale biography.

Sandra Martin is a writer and journalist living in Toronto.