Published in 2018, Pamela Mulloy’s first novel, The Deserters, is the tragic love story of a lonely wife on a farm in New Brunswick and an American soldier who goes AWOL while on leave from Iraq. Whereas that slim book examines an aftermath of war, specifically post-traumatic stress disorder, Mulloy’s latest work explores how the prelude to war can dramatically transform the lives of everyone involved.

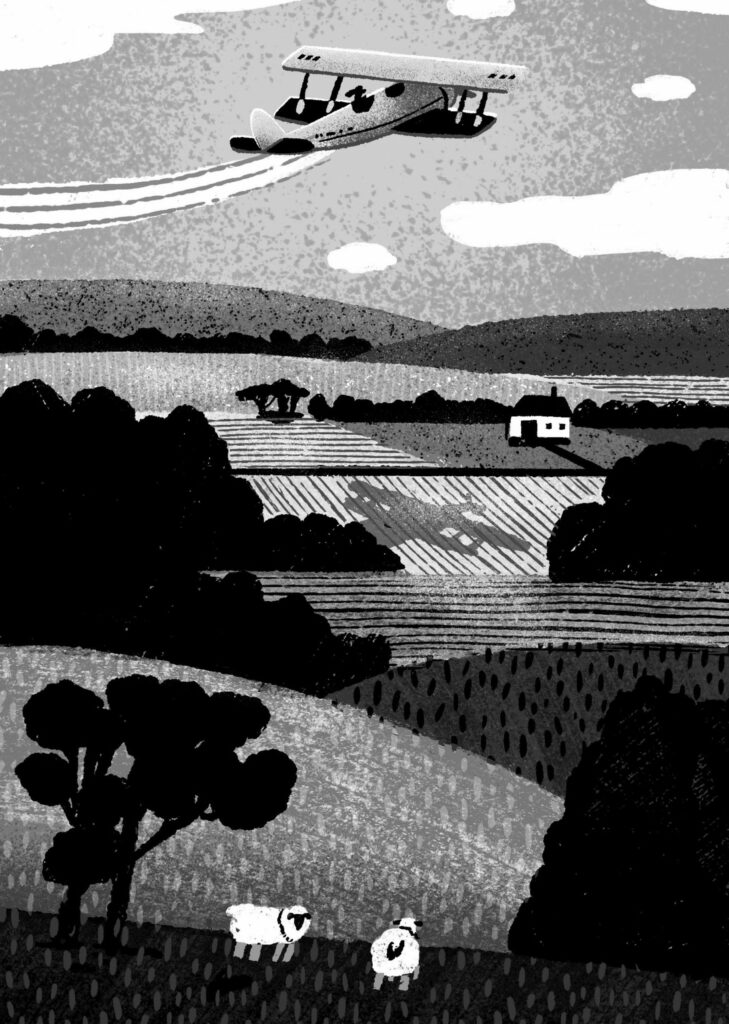

As Little as Nothing is set in the English countryside on the eve of the Second World War. The inciting incident occurs when Miriam Thomas, the artistically talented but frustrated wife of a village shopkeeper, is lying despondent in bed in her bucolically named Hawthorn Cottage. Recovering from a fifth miscarriage, she hears an airplane overhead. It is in trouble, the engine sputtering and coughing. The day is Thursday, September 1, 1938, precisely one year before Hitler’s invasion of Poland.

Almost all of As Little as Nothing takes place in the twelve months that separate peace from bloodshed. Miriam longs to escape, to free herself from her body and from the earth. She dreams of flying and has Chagall-like visions of herself, arms spread, drifting weightlessly over the village. Upon hearing the struggling motor, she sets off, despite her weakness, to find the downed plane. “She barely knew where she was going as she stumbled down the stairs and outside to her bicycle.”

Frank Wentworth, an upper-class young man with a bad limp and suppressed homosexual yearnings, also has dreams of flying. He signals to the distressed pilot to land on a nearby roadway and rushes to the crash site. He finds the biplane, a Gypsy Moth trainer, with its motor dead and nose down in a ditch. The aviator — bleeding and unconscious — is trapped in a tangle of brambles. “Frank took a few steps to the tail, glad for a task, then stopped. It was thrilling and terrifying, this adventure. What would they think of him? To have rescued a pilot. It was only later that he considered who he meant by ‘they.’ His family.” Miriam arrives soon after Frank and, with the help of his chauffeur, they drag the aircraft back onto the road, where Frank eagerly frees the handsome flyer from the cockpit.

A splendid portrait of a portentous year.

Sandi Falconer

Later, Frank introduces Miriam to Audrey Wentworth, his charismatic, elegant, and extremely independent aunt. A tireless advocate for women’s rights, birth control, and access to abortion, Audrey is a luminous figure, living in an isolated caravan and swimming alone, sometimes naked, in the deep, narrow local river. As a younger woman, she used to race around England, solo, on a powerful motorcycle, but “these days she only left her caravan to campaign.”

Frank encourages Miriam to learn to fly, so that she might turn her misty reveries of escape into soaring reality. And Audrey — who served as an ambulance driver in the First World War and is intimate with the sight, smell, and feel of burnt flesh and death — introduces her to early feminist thinking and the struggle for reproductive rights. “Audrey talked about abortion activist Stella Browne, and the advancements she’d made, gave Miriam a pamphlet that was used in other clinics.” As a counterweight to these heterodox, liberating energies, there is Edmund, Miriam’s fuss-budget husband who yearns to be a father.

Edmund is gently pigheaded and “impossible to argue with.” He takes refuge from Miriam’s daring vitality and from rumours of war by cultivating his garden with myopic and mystical intensity and by obsessing about his daily routine: tea, for instance, must be served at a precise time each afternoon. While Edmund deeply and desperately loves Miriam, he is appalled by her bold spirit and puzzled by her growing feminism. He is also, perhaps, jealous of her new-found eccentric friends, Frank, Audrey, and Peter, the downed Canadian pilot.

Behind all of this is a menacing backdrop: the Munich Agreement, the betrayal and dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, the lead-up to the invasion of Poland. As the drumbeats of war become louder, Edmund fears for the peace and quiet of his village existence. Miriam, however, glimpses possibilities of adventure, of truly taking flight, and of giving a wider, deeper meaning to her life. Frank is eager to serve in whatever way he can. And Audrey, recalling the horrors of an earlier conflict, sees her campaign for women’s reproductive rights being swept aside into irrelevance. She realizes that she must now find a different task to give renewed meaning to her life.

Mulloy crafts her narrative with superb skill, brilliantly evoking each character’s vivid, sensual individuality. She artfully alternates points of view, often plunging us in medias res — into the midst of a mind’s actions, realizations, or intimations. Tactile sensations, details of perception, and subtle shifts of mood abound as she recreates the easy or turbulent ebb and flow of thought, as it drifts to the past, focuses intensely on the present, or takes flight toward the future.

“No one had ever observed her with such singularity,” the narrator explains as Miriam reflects on first meeting Edmund. The comment could apply equally to Mulloy’s approach to her characters. Each has a universe soaked in vibrant symbolism, rising semi-consciously from their immediate environments and experiences, whether the refuge of a cool stream, the transcendent beckoning of the blue sky, or the constricting prison of a water-soaked nightgown lightly cast aside.

Mulloy’s novel gifts us with a splendid portrait of a unique time and place, as well as a group of people who lived, loved, and struggled with ferocious intensity, each emanating vital singularity. When we take leave of them in September 1941, they are still very much alive. And Miriam, now a pilot, is in the very midst of the action.

There is, it must be said, an elegiac aftertaste to this tale. This elegiac mood lies not within the story, however, but outside it, in the title. When we close the book, those people we have come to know so intimately freeze into poses, like characters in an ancient Roman fresco. They are reduced, as we all are so quickly in real life, to two-dimensional wisps of memory. We know that as new generations come and go, Miriam, Frank, Audrey, and Edmund will fade from our thoughts until they become less and less. Until, finally, they are “as little as nothing.”

Gilbert Reid is a writer for television and radio.