Recently, the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton exhibited a striking collection of tapestries and prints from the Micmac Indian Craftsmen, a short-lived and mostly forgotten studio associated with Elsipogtog First Nation, then called Big Cove, in New Brunswick. Those who missed the show can learn about this “vibrant co-operative experiment” from the beautiful catalogue by the curators Emma Hassencahl-Perley and John Leroux. In English, Mi’kmaw, and French, Wabanaki Modern offers a comprehensive look at the production of commercial handicrafts by “the first modern Indigenous artists in Atlantic Canada.”

The formation of the MIC in 1962 was, in part, a response to the Massey Commission’s observation, a decade earlier, that “cultural and artistic vibrancy was vital to the social and intellectual health of Canada’s Indigenous Peoples,” as Leroux puts it. The provincial director of handicrafts in New Brunswick at the time, Ivan Crowell, had arranged to meet with community leaders in Big Cove in 1961 to conduct a few trial classes. (Leroux describes Crowell as a “respected master weaver, teacher, and pewtersmith” in his own right.) The following April, the New Brunswick Department of Industry and Development received a $7,000 grant to provide further training to the community and “encourage the development of a handicraft producing enterprise.” Crowell praised the “tremendous reserve of undeveloped talent” he felt he had discovered. With government support, and by tapping the participants’ abilities and proclivities, he thought he could help economically stimulate one of Canada’s poorest populations and establish a semi-industrial handicraft operation that would have an “unlimited market.”

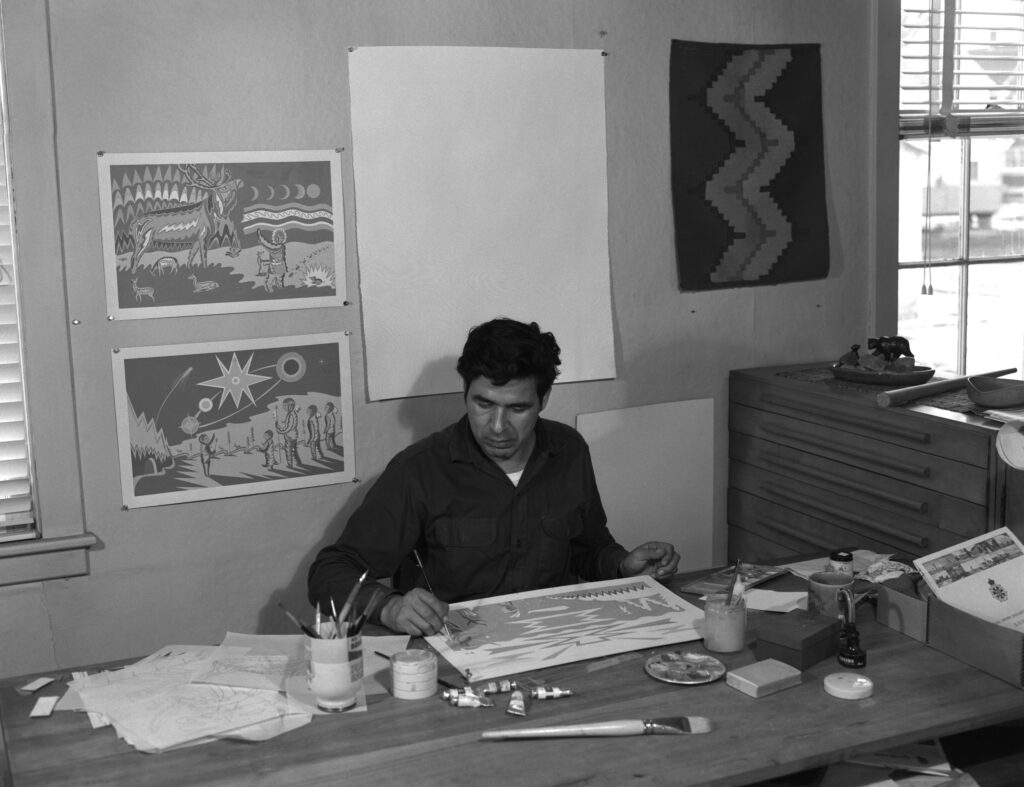

The Mi’kmaw artist Michael Francis working on his Canadian Indian Legends series, in 1964.

Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, P14-2-7421; Courtesy of Goose Lane Editions

But there would be “growing pains” when it came to “business and technical skills.” F. B. McKinnon, the regional supervisor of Indian Affairs in the Maritimes, noted that most members had received next to no instruction in “color appreciation, balance, tones, and whatever else a designer’s work should reflect.” And so initially the studio produced souvenirs and functional objects designed by the white instructors. But even as members of the MIC began to assume a larger creative role, their “roughed out” pieces had to be sent 320 kilometres to Fredericton for review and modification. Crowell eventually brought in the Mi’kmaw artists Michael Francis and Stephen Dedham (sometimes spelled Dedam) to take on leadership roles, but always with Crowell’s oversight.

The principal visual motif of the Wabanaki Confederacy is the Double Curve, an expansive and pliable symmetrical design that appears sparingly in the catalogue, because, in an attempt to appeal to avant-garde sensibilities, the MIC explored an array of contemporary styles. Their most successful product, a series of postcard-like “hasti-notes” manually silk screened on thick paper and sold in hand-sewn burlap bundles, was “rendered in a clean, abstracted approach using bold line, colour, and dramatic composition.” The Micmac Legend of Our Seasons, the first series of cards created entirely by Francis, riffed on visuals from the Diné and Hopi Nations and the geometric patterns typical of the American Southwest. In an era when the Pan-Indian movement had introduced dream catchers and feathered war bonnets as symbols of a common Indigenous experience, the notecards seemed to satisfy consumer tastes.

At its peak, the MIC had twenty craftspeople who could print 200,000 hasti-notes annually, but payroll amounted to a mere $1,000 per month. Even though the cards sold well, the studio “began refusing to take repeat orders as they did not have the manpower to fulfill demand.” Workers often went unpaid and left for a steady income as labourers in Maine. In June 1964, concerned officials from Ottawa visited to see whether “expenditures were justified in relation to the benefits being obtained by the Indian participants.” Problems with management, retail operations, and cash flow began to surface, prompting the Indian Affairs agency in Chatham, more than an hour away, to assume control of the MIC’s accounts. The federal department then declared that the group had to be “self-managed and operated on or before September, 1965.” Crowell entertained various money-making ideas, including having the members give canoe rides to tourists and perform Wabanaki stories as puppet shows. After its funding was withdrawn in 1966, the group dissolved.

Hassencahl-Perley and Leroux depict Crowell as overeager if well intentioned, and the limits of his ambitions are apparent; he failed to cultivate that “reserve of undeveloped talent” quickly enough to convince granting authorities to continue their support, and the enthusiasm his classes met with never translated into a successful commercial enterprise.

There’s a paradox to this story. In his foreword, the curator and art historian Gerald McMaster points out that, for generations, “Indigenous artists could not create art for their own reasons, which is to say for cultural purpose and ceremony.” By the time of the Massey Report, “knowledge keepers were far fewer and ceremonial life had largely been replaced by Christianity.” It’s no wonder that, when federal and provincial governments sought to reinvigorate communities like the one at Big Cove, they found local skills were lacking. The MIC was given just four years to shake off a “cultural atrophy” that had been taking place for much, much longer.

Patrick Leonard is a Canadian curator and writer based in New York City.