In 1663, a physician to Charles II named Constantine Rhodocanaces published a pamphlet celebrating the wonders of his recent concoction. Alexicacus, Spirit of Salt of the World claimed that the substance we know today as hydrochloric acid could be “Philosophically prepared and purified from all hurtful or Corroding Qualities.” The aqueous solution was not new at the time, but Rhodocanaces sold his product as the only safe version: it was a veritable “averter of evil,” as suggested by the title of his little book, and could be used against headaches, intoxication, worms, and “putrifaction of anything in the Stomak.” It could even ward off “all filth, or slime,” from the arteries and banish “the water that lurks betwixt the skin and flesh.”

The director of McGill University’s Office for Science and Society, Joe Schwarcz is fascinated with the successes of fraudsters like the king’s doctor, past and present. With his latest book on the subject, Quack Quack: The Threat of Pseudoscience, the healthy skeptic serves up seventy-three vignettes about some of the myths, lies, and even wishful thinking that have masqueraded as science — especially medical science.

In this pun-filled, energetic collection, we read how charlatans through the centuries have employed the same tricks of the trade, enticing “the desperate and the worried-well” with bogus testimonials, slander, and “claims of secret breakthroughs.” Some of those dubious assertions have even seeped into our language. At the 1893 World’s Exposition in Chicago, Clark Stanley, known as the Rattlesnake King, split open a viper, submerged it in water, and skimmed off the floating fat. The resulting Stanley’s Snake Oil was supposedly an excellent treatment for arthritis. In fact, the “liniment” Stanley sold didn’t contain anything from the reptile: it was a mixture of mineral oil, turpentine, camphor, beef fat, and red pepper. But, like Rhodocanaces before him, the Rattlesnake King knew how to sell his stuff: he claimed that snakes didn’t suffer from joint pain because they were, as Schwarcz puts it, “well lubricated internally.” The crowd “lapped up the hype and shelled out the money.”

You won’t find spirit of salt or the Rattlesnake King’s unguent at a pharmacy today, but then people don’t always turn to experts for remedies. If you want to eliminate all that filth and slime, you might consider a patch to draw out the bad stuff and infuse “healing agents into the body,” including vitamin C and laetrile (which can cause cyanide poisoning). Or you could start a detox diet. But, Schwarcz says, even if you feel better after cutting out caffeine or fasting — apparently “near-starvation can trigger a boost in energy and even feelings of euphoria”— the concept is flawed. “The fact is,” he writes, “that our bodies are engaged in detoxication all the time.” That’s what livers and kidneys are for. Periodic purgation of our “dietary sins” doesn’t improve health, at least according to the science.

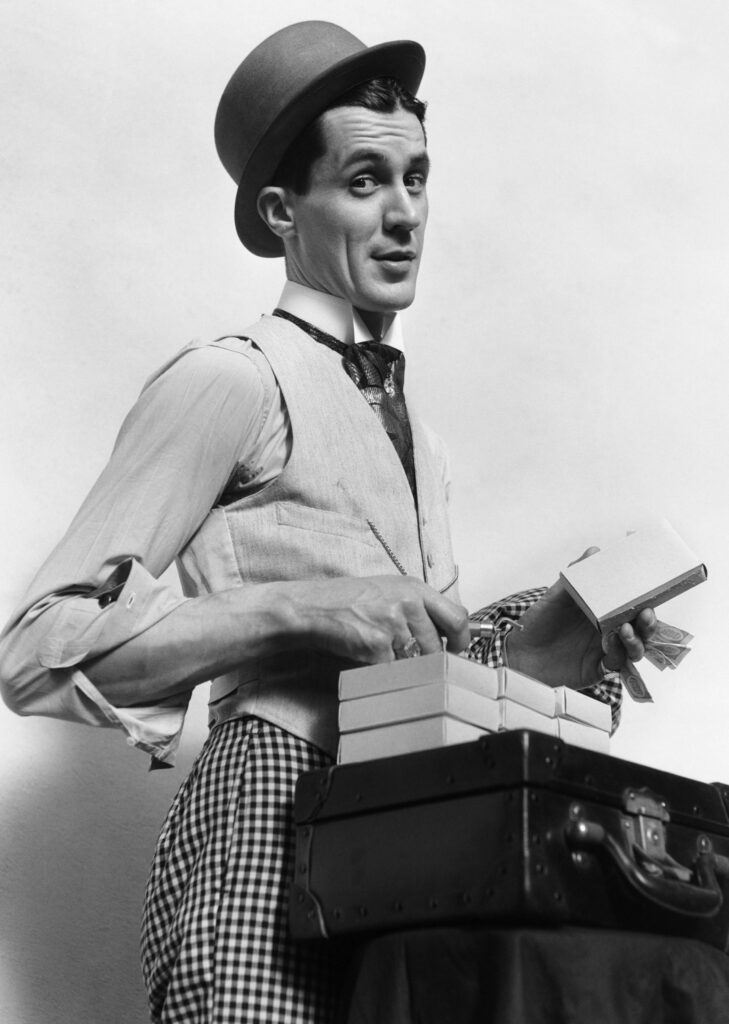

Hawking products full of hype, not science.

ClassicStock; Alamy

Schwarcz further considers the fixation on the “natural” lifestyle, like the recent trend of drinking “raw water.” One Christopher Sanborn, who now goes by Mukhande Singh, says he had a “revelation” one day that bottled water was filtered, sterilized, and irradiated to lengthen its shelf life and “to save costs.” Singh came up with a different solution, which he sells under the brand name Live Water. His product comes from a “remote spring” in Oregon and is, he claims, far healthier than the “toilet water with birth control drugs in them” that flows from the tap. To be fair, Schwarcz points out that there is no evidence Live Water “harbors disease-causing organisms,” but the same cannot be said of all “raw” varieties. The real danger here is that Singh ignores the science behind water treatment. And he’s capitalizing on people’s gullibility.

What makes us fall for it, though? Schwarcz doesn’t explore that larger question, but the variety of the cases he examines does suggest some plausible reasons to buy into pseudoscience. Sometimes the quacksalver is able to leverage a person’s mistrust of the pharmaceutical industry — though that doesn’t explain why one source should be deemed more trustworthy than another. Sometimes the “alternative medicine” is cheaper or more readily available. If prescription drugs are too expensive, why not try the do-it-yourself solution? (Despite the lack of evidence for its effectiveness, apple cider vinegar is used to treat everything from arthritis and skin conditions to heart disease, likely because it is cheap.) And sometimes it’s simply that an influencer or celebrity with a less than thorough grasp of science is selling a story they themselves believe. Schwarcz refers here to Jamie Oliver’s repeated claim that ice cream sundaes contain lac bugs, human hair, feathers, and beaver glands. The chef’s desire to “improve students’ health” is commendable, but his concerns here are, Schwarcz says, misplaced. It is true that “a few parts per million of purified castoreum” can fall under the category of natural flavours, but “that’s a long way from mixing beaver glands into ice cream.” (Incidentally, this fluid emitted from castor sacs is quite expensive and has been used in homeopathy. What’s good for the goose . . . )

Then there are those occasional instances of “pathological science,” a kind of wishful thinking that happens when trained experts unwittingly deviate from the scientific method. When the electrochemists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann announced in 1989 that they had “detected the fusion of deuterium nuclei under simple laboratory conditions,” the scientific community stirred with anticipation, but no one was able to reproduce the results. There was no “cold fusion.” It seems the two “had noted some anomalous phenomenon but had misinterpreted their findings.”

Quack Quack is not an exploration of human psychology, but Schwarcz does think science educators can help combat some of those false hopes we’re all susceptible to. He closes his book with a list of twenty-five “Views on Dealing with Information and Misinformation,” which read a little like the bits of advice an experienced adult might give to a young person leaving home for the first time: “Education is not a vaccine against folly”; “There are no geese that lay golden eggs.” None of these aphorisms is particularly groundbreaking, but then part of Schwarcz’s achievement as a science communicator is his no-nonsense, entertaining way of reminding us to take all miraculous, untested claims with a grain of salt.

Tareq Yousef is a neuroscientist currently lecturing at the University of British Columbia.