In 2004, the arts activist and critic David Gere published his seminal work, How to Make Dances in an Epidemic: Tracking Choreography in the Age of AIDS. “In this era,” he wrote, dancing “commonly serves a mourning function, with fetishes of loss and longing literally embodied in the corporeality of the performers.” Twenty years later, Gere’s book finds an updated, French-language counterpart in Lucille Toth’s Danses et pandémies: Du sida à la covid-19 (Dance and pandemics: From AIDS to COVID-19). With her short volume, the choreographer and scholar primarily explores the francophone dance world’s rich variety of reflections on HIV’s impact on social relations. In a closing chapter, she gestures to the growing relevance of digital space for amateurs and professionals alike today.

Toth begins with the French choreographer Alain Buffard and his 1998 solo piece, Good Boy. When it premiered at the Ménagerie de verre in Paris, it marked a historic departure by shifting the focus from bereavement to the vigilance required to battle a communicable disease. Buffard, naked at the start, pulls on pair after pair of Y-front underwear, building up a thick pad. The fabric holds and contains a body that has been made incontinent by the illness, while the movement, Toth argues, symbolizes an exertion of control. With the constricting layers of material, the dancer neutralizes his own sexuality as a gay man — a burden imposed on him by a society looking for a scapegoat.

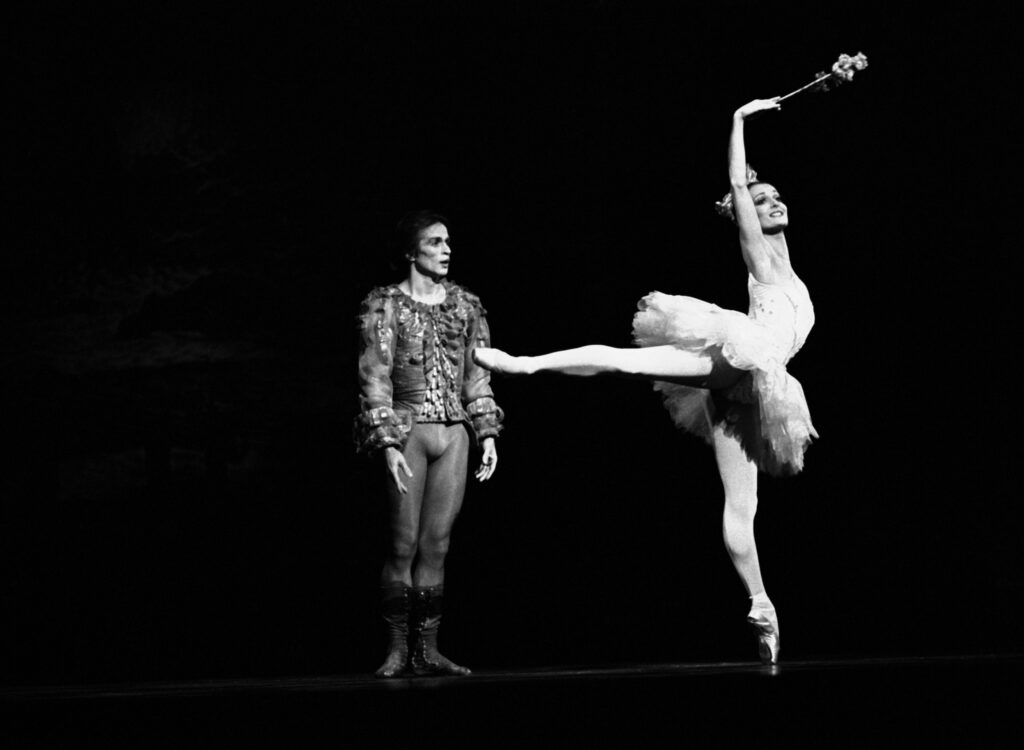

Toth goes on to ask whether it’s possible to evoke death and suffering without recourse to victimization or sublimation. She points out that the Russian ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev (spelled Noureev in the book) never hid the pain involved in training — pain he claimed vanished during performances. The physical afflictions he endured while living with AIDS could be partially channelled into his art, and it was easy for others to overlook any discomfort: healthy dancers hurt all the time. As Nureyev became sicker, however, he altered the Paris Opera Ballet’s choreography by toning down the other dancers’ technique. Like the makeup and costumes used in the nineteenth century to mask signs of syphilis in ballerinas, Nureyev’s artistic choices disguised his medical condition. Personifying the ideal prince of Romantic ballet left plenty of room for suffering but none for frailty and certainly none for AIDS. It was only after he died that his doctor disclosed his illness.

Toth suggests that some conventions, like those of ballet, lend themselves to camouflage and denial. Contemporary dance, on the other hand, allows for a more open display of what a virus does to a body. The illustrative contrast works with Nureyev and Buffard, but it doesn’t hold in all cases. For instance, Thomas Lebrun’s 2013 Nouveau Théâtre de Montreuil production, Trois décennies d’amour cerné (Three decades of fenced-in love), features a tender pas de deux, in which Toth sees a renewed possibility of intimacy and touch. Here, the dance partner is the only protection one needs — emotionally but also literally — against falling. Whereas Good Boy points to HIV’s isolating effects on the individual, Lebrun is able to respond to the disease’s impact on the environment and on others while presenting a kind of defence and acceptance that involves community. The fact that he does so using ballet conventions is worth exploring, but Toth gives it just passing mention.

Rudolf Nureyev performs with Monique Loudières in 1983, shortly before his HIV diagnosis.

Thierry Orban; Sygma; Getty Images

In places, Danses et pandémies prioritizes thematic breadth over analytical depth. Addressing the racial and gender dynamics of the ongoing AIDS epidemic — like the disproportionately high rates of infection among young women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa — Toth races through four dances from four countries in a single twenty-page chapter. Women appear, disappear, die, and are reborn in these works, but the author’s analysis remains superficial. She suggests, for example, that Lebrun’s Les yeux ouverts (Open eyes), from 2014, offers a new reading of the epidemic, but she never shows us how. Instead, she moves on to her next subject. Surveys can be useful, but the approach clashes with her profound observations earlier.

The final chapter, which reads like a coda, focuses on COVID-19 and makes only tenuous references to previous arguments. Questions of physical and emotional pain mostly give way to an interest in technology and society. Toth considers the young influencer Keara “Queen Keke” Wilson and her 2020 viral TikTok video: a dance to the rapper Megan Thee Stallion’s hit song “Savage.” Marvelling at how a performance spread by social media can connect people, Toth devotes several pages to discussing hashtags and calls Wilson’s choreography a hymn of the first lockdown, though it’s hard to see what exactly she means. It would have been helpful, as well, to compare a clip that goes viral with historical examples of collective embodiment, like Orphic rituals, the European dance plagues, or underground raves. Wilson’s precise, exuberant movement is a product of the pandemic, but it isn’t about the pandemic. In many ways, it recalls Nureyev on stage trying to escape his pain.

Overall, though, Danses et pandémies is a welcome contribution that shows how choreography has evolved over the decades to reflect the wants and needs of artists — whether through sublimation, transcendence, elegy, or celebration. Gere wrote that the “terrain of signification related to AIDS is vast and, in many regards, volatile and uncontrollable.” By offering moments of illumination of more recent examples, Toth shows how that statement is still true.

Ruth Jones is one of the magazine’s contributing editors.