Since starting high school in our small township flanking the agricultural countryside outside of Guelph, Ontario, my daughter has remarked more than once on the copiously white student body. While she’s amused by events like “Take Your Tractor to School Day,” she’s also aghast that there are only a smattering of students of colour, and she occasionally wonders aloud how it feels to be one of the two or three Black teenagers in the entire building. What troubles her most? The seeming casualness with which racist epithets are sprinkled into everyday conversation.

But recently, during a day trip to Toronto, we witnessed a deeply unsettling encounter on the transit system, which challenged any preconceptions we might have had about such explicit racism being unique to rural communities like ours. Commuters were quietly keeping to themselves when, with a single word hurled in hate at a Black passenger, a white man thrust a violent past into the immediate present.

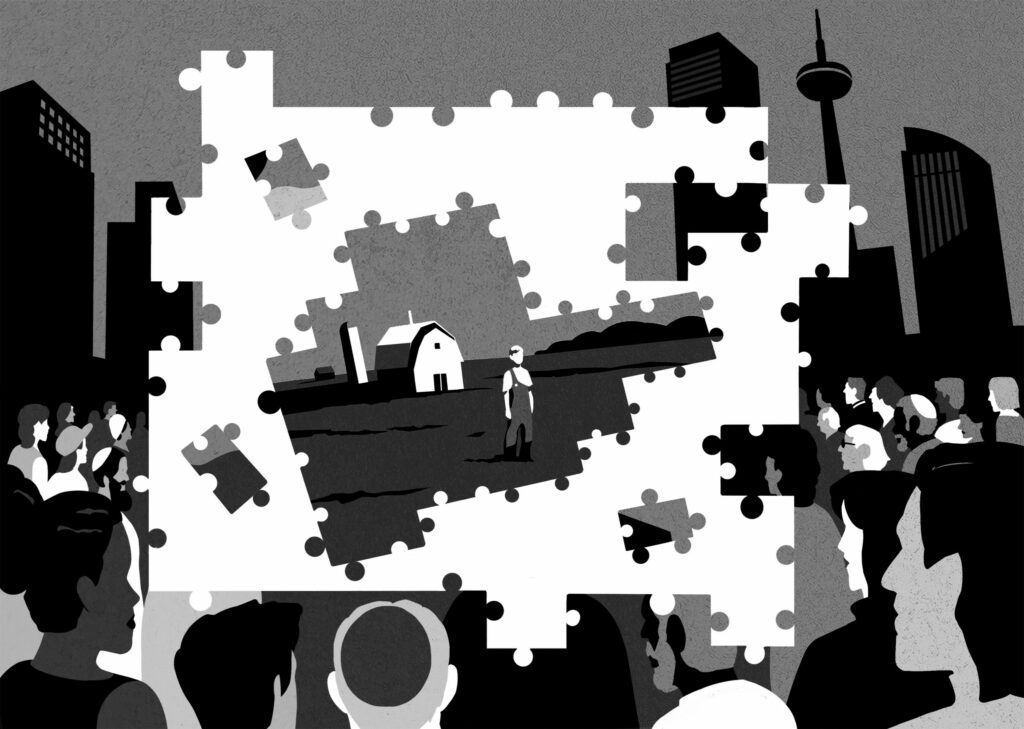

Piecing together a clearer picture of rural Canada.

M.G.C.

We spoke later — my daughter and I — about an urban-rural divide that imagines Canadian small towns and countryscapes as invariably backward and bigoted, in sharp relief to the supposed inclusiveness of the metropolis. And research does reveal that older age, lower education, religious commitment, economic insecurity, and fears of cultural loss all correlate strongly with intolerance. Each of these factors is a feature of rural demographics. Still, it’s too easy to resort to tired tropes of a racist backwater without digging deeply into the realities of small-town life. Clark Banack and Dionne Pohler’s essay collection, Building Inclusive Communities in Rural Canada, plants some critical seeds in a research field relatively barren of sustained inquiry. To what extent, their contributors ask, does racial intolerance prevail in rural Canada, and how do we create more inclusive rural communities in this country?

In posing these questions, they push us to probe beyond the stereotypes — white, Christian, conservative, blue-collar, uneducated, anti-Indigenous, anti-immigrant — and to look beyond the headlines about, for example, the murder of Colten Boushie on a central Saskatchewan farm or the burning of a Mi’kmaw lobster plant in southern Nova Scotia. With the aim of “nuancing the rural,” each of the contributors challenges the limits of their own academic training. Not one of them could be counted as an “expert” on diversity and inclusion in rural Canada — and, in fact, no such experts exist despite heaps of urban-focused equivalents. Refreshingly, these writers refuse to brush off rural Canada as a hotbed of xenophobia and general intolerance, instead acknowledging and celebrating the work of inclusivity that is already being done, while critiquing the discriminatory attitudes that still prevail.

Arguably, the fear of being “left behind” culturally and economically makes rural areas easy pickings for far-right recruitment. Research out of the United States reveals that rural grievances translate into resentment toward minorities, with rural identity predicated on anger and on a fear that rural life is under siege. Donald Trump’s populist base, for example, is filled with legions of rural voters. There is little comparable research in Canada; we know almost nothing about how tolerant, or not, rural Canadians really are.

What we do know is that small communities on this side of the border are experiencing a downturn in the fossil fuel industry, competitive pressures in agricultural production, and the loss of primary industries due to globalization — not to mention declining infrastructure and a steady exodus of young people. All these trends contribute to feelings of scarcity, economic deprivation, and political resentment, feeding an acute sense of disenfranchisement to which these gathered observers — mostly rural folks themselves — are sensitive.

Given the dearth of data, it’s a specious leap to claim with anything approaching certainty that rural Canadians are anti-immigrant. As Banack and Pohler point out, the sparse evidence that does exist, such as an Angus Reid survey from 2019, renders suspect such blanket claims. While small, the survey sample showed that urban and rural respondents were closer than one might expect in their perceptions of the growing presence of immigrants in their communities. Such data hints at more complex rural realities, as does the development of co‑operatives among “rural settler and Indigenous communities” and rural-based refugee sponsorship programs.

To put it differently, rural Canada is more diverse — and often more inclusive — than many people think. The statistician Ray D. Bollman makes this point in the book’s opening chapter, backing it up with figures that reveal how Indigenous populations are flourishing in many places and how immigrant communities are slowly gaining a foothold. The Hallmark-movie small town, filled with folksy white people and quaint little shops, is, not surprisingly, mere myth. Given the changing demographics beyond urban centres, elected officials ought to heed the contributors’ call for services, policies, and practices that both meet newcomers’ needs and foster relationship building.

This urgent call unifies an otherwise wide-ranging collection. The essays — some, unfortunately, marred by dry-as-toast prose — run the gamut, from analyses of rural diversity as a challenge in Quebec schools to considerations of Protestant evangelical inclusivity.

The co-editor Clark Banack’s standout chapter on attitudes toward cultural and religious minorities is a must-read for anyone who picks up this volume. An ethnographer who shows up unannounced and listens to coffee shop conversations in rural southern Alberta, Banack employs listening as a research method for investigating a question on the minds of many Canadians these days: How do so many white Albertans come to hold the opinions they do, especially when it comes to Indigenous communities and other people of colour? His fascinating answers should be required reading for federal policy makers and community educators alike.

Aptly describing the perceived alienation of rural Albertans as “layered,” Banack pierces the heart of the matter: for many, there is a keenly felt sense of being alternately misunderstood, judged, and ignored by urban elites. These grievances translate, troublingly, into anger directed squarely at Indigenous and immigrant groups. Banack’s conclusion is spot‑on: any efforts to quash racial discrimination in rural Alberta will undoubtedly fail unless they begin by acknowledging — with empathy — experiences of alienation among local residents. “Only then will the opportunity arise for authentic learning, bridge-building, and reconciliation across cultural divides in rural communities,” he insists.

Banack’s principled insistence on ground‑up solutions is echoed in other essays. Parsing a rash of racist incidents in Owen Sound, Ontario, the political scientist Phil Henderson examines the language of tolerance that infuses top‑down approaches. Is such vocabulary likely to find traction, he asks, among rural folk apt to see it as an urban import and imposition? Why not use a more palpable vernacular to attempt to achieve the same ends? Building on the language of the good neighbour that is already familiar in non-metro spaces, Henderson wonders what “radical neighbourliness” might look like in rural communities. How can a discourse that already exists and is part of the everyday lexicon be extended to ask such questions as “How can I be a good neighbour when the very ground on which I make my home is being expropriated from the Indigenous peoples who have governed and cared for it since time immemorial? How can I be both neighbour and guest?”

Similarly, the political scientist and documentarian Roger Epp suggests that what we need in these polarized times is a way of talking that moderates and de‑escalates. Drawing on First Nations legal traditions, as well as the Biblical story of the Good Samaritan, he argues that the language of neighbourliness that is already prevalent in rural spaces stands a better chance of building trust and reciprocity than the currency of “reconciliation.”

A glaring omission in this collection is the perspective of Indigenous thinkers who could speak to the place of neighbourliness in, say, Anishinaabe teachings and traditions. In a scholarly collection on the very theme of inclusion, it seems a misstep to assemble mostly white academics, regardless of the intention to meet “rural settler communities” where they are. Nonetheless, there is something hopeful about many of the practical suggestions that fill these pages.

Being a good neighbour is certainly a habit I try to instill in my daughter. It is also part of a rural ethos and lexicon that already makes sense, I suspect, to my other rural family members, who might otherwise groan at an increasingly corporate and governmental discourse of tolerance, inclusion, and diversity. The neighbour, as Epp reminds us, is “not the one who is like you” but simply “the one who acts like a neighbour, and who takes no small risk in doing so.” Anti-racist theory and praxis are already emerging in rural settings. They’re just waiting to be boldly and imaginatively repurposed with the vision of creating deep equality.

Julie McGonegal is the author of Imagining Justice: The Politics of Postcolonial Forgiveness and Reconciliation. She writes from Elora, Ontario.