Fiction is like a game. As in sports or virtual reality, rules are established at the outset of a fictional story. How many characters will there be? What capacities do they have? Is the action restricted to a tiny space, maybe a house or a village, or is it dispersed across galaxies? Over what span of time does the story unfold: A single day? Centuries? Since every story takes place somewhere in space and time, why does an author choose one space-time continuum and not another?

However broad or narrow, frameworks of time and space regulate characters’ conduct. If the parameters of the story permit, characters may possess superpowers, such as an ability to shoot spiderwebs from their wrists. Or they may be ordinary folks in an ordinary town on an ordinary day facing ordinary problems. Once their motivations and roles have been determined, they should respect the rules of the representation and not suddenly transform into some other sort of being. They have to obey the logic of the worlds that they inhabit. It would be unthinkable, for instance, for characters in an Alice Munro story to swing daringly from tall buildings while saving a city, like comic book heroes. By setting rules for place, time, and action, fiction establishes possibilities that run parallel to and intersect with reality.

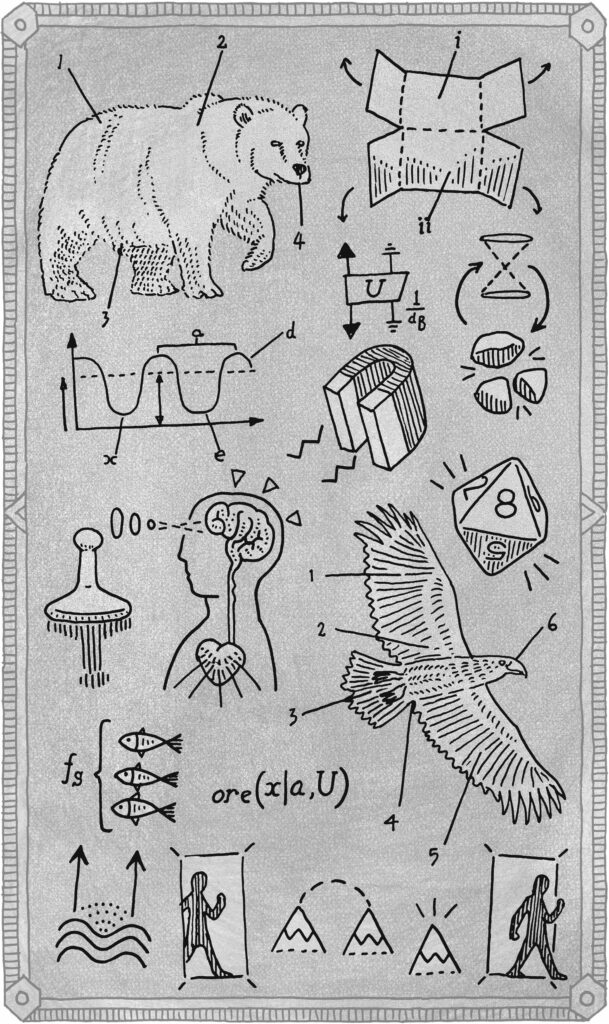

In Thomas Wharton’s marvellous new novel, The Book of Rain, a character named Alex designs board games for a living. These involve murder mysteries, magic, secret societies, and imminent catastrophes of one kind or another. For the sake of verisimilitude, Alex draws upon facts and history when designing games, while charting courses for alternative realities — paths not taken — through time and space. Like a novelist, Alex sets rules about how characters move and where they move to, with no‑go zones determined by hostile agents or environmental toxicity. Through games, he builds alternative worlds with internally coherent time-space continuums. Because of his success as a creator of games, Alex is hired by a virtual reality company that is devising an “innovative online ecosystem” filled exclusively with animals — no human beings allowed.

As a novel about alternative worlds, The Book of Rain descends literarily from Jorge Luis Borges’s “The Garden of Forking Paths,” Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. In these fictional realms, possibilities branch out and time takes on magical properties, as in the famous first line of García Márquez’s novel: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Wharton works variations on that sentence, but nowhere more slyly than in a reference to Alex’s game making: “He next tinkered with a game based on his memories of the Northfire ore-processing complex his father had taken him to see all those years ago.”

Building alternative worlds and realities.

Tom Chitty

In Wharton’s tale as in García Márquez’s, time bends into unexpected shapes. The Book of Rain opens on Tuesday afternoon and ends on Wednesday evening, as if only a few hours have passed between the first and last chapters. Blips in time and space are among the most wonderful effects in the novel. Occasionally something happens in a dream that meets up with something that happens in reality, or the deep past coincides with the future to create giant time loops. At one point, Alex dreams of carrying a young boy on his back through a snowstorm, and this event, seen a second time from a bird’s‑eye point of view, turns out to be a key moment in the life of his great-nephew, who is not yet born when the dream occurs.

Although they abide by different timelines and spatial configurations, stories interlock. The main characters — Alex, Claire, Amery, Michio — feel they are “caught up in a story,” although they do not know what part they are playing in that scenario. They move around “in a world not of their own making, subject to laws they didn’t understand.” Drawing upon personal experience for one of his games, Alex creates a role-playing adventure for four competitors who draw cards from a “Story Deck.” Like a garden of forking paths, the game has many “twists and unexpected outcomes”— so many, in fact, that the players can tell their pasts “over and over again, imagining how things might have been different,” without exhausting all the possible trajectories.

Alex admits that he creates games to discern patterns in reality. Another reason to build them — or to write novels, for that matter — is to figure out how to deal with anthropogenic crises on Earth. In the story world of The Book of Rain, biohazards, environmental degradation, droughts, wildfires, rising sea levels, species extinction, pandemics, and capitalistic energy extraction have all taken their toll on sustainable life on the planet. In a pithy summary, Alex’s sister, Amery, draws a distinction between imagined worlds and actual environmental catastrophe: “Alex makes impossible worlds. We’re making this world impossible for ourselves.”

Wharton’s mission, like Alex’s and Amery’s, is to imagine alternative realities. Can human beings avoid total calamity, especially when they are responsible for so many smaller catastrophes? What might the world look like and how might human beings behave if they listened to the distress signals sent out by animals and the earth itself? Is human extinction inevitable?

The Book of Rain takes place in and around River Meadows, a town in northwestern Alberta known for the extraction of “ghost ore,” a combustible fuel with “possible harmful effects.” The ore must be disaggregated from its sand and clay matrix, a process that is both “unreliable and dangerous,” much like the extraction of petroleum from the oil sands. Extraction causes a boom in the local economy: a single gram of ghost ore is rumoured to be worth twenty-eight grams of gold. Massive pits are dug; gigantic extractors spring up. Yet weird things happen in River Meadows. Doors open and close of their own accord. “Decoherences,” known locally as “wobbles,” disrupt space and time. These disruptions might last a few moments without serious consequences — mere “ripples”— or they might trigger devastating explosions. When she first experiences a decoherence, Amery falls asleep for seven days. After a while, people in River Meadows accept them as routine and stop talking about them.

The mining company denies that ghost ore has any relation to the decoherences. Nonetheless, protesters claim that mining operations poison the environment and reduce biodiversity. Tailing ponds trap and kill animals by the thousands. Eventually, a disastrous accident prompts the evacuation of the town, and several hundred hectares are cordoned off as unsafe for human habitation. Inside this Environmental Reclamation Area — or the Park, as most locals call it — strange events occur. Balls of energy, invisible but powerful, gather and seem to attack people. Scientifically minded observers think of the bursts as “some form of energy we don’t yet understand.” Superstitious folks call them “the Visitors.” Whether natural or supernatural, these bursts cause space to pucker and time to collapse. When Michio leads Alex into the Park and into the path of these energy bursts, he warns him in language that Alex might understand: “This isn’t a game.”

Inside the Park, Alex sees a herd of woodland caribou, a critically endangered species. In fact, The Book of Rain keeps a running account of animals that have gone extinct or are on the brink of disappearing, almost always because of human encroachment on their habitats: auks, sapphire frogs, Kitti’s hog-nosed bats, “thought to be the world’s smallest mammal, discovered only in the late twentieth century.” Out of rapacity or fear, human beings wantonly kill animals. Alex bashes a fox to death with a stick. A religious fanatic shoots a deer to prove his marksmanship or to demonstrate his superiority over wildlife. Sometimes the motives for killing other creatures are even more sinister: Claire smuggles rare animals or animal parts, such as skins, from one country to another on behalf of invisible and anonymous traffickers.

Of all the characters, Amery shows the greatest willingness to live with and understand non-human beings. Just as Sir Richard Burton, who translated The Arabian Nights in the nineteenth century, tried to learn monkey language, Amery eventually learns to speak an avian language, known as “the Uttering.” Through listening and observation, she communicates with goshawks, sparrows, and other birds.

Thus, a long fable about environmental catastrophe and survival, featuring a chatty magpie named Yap, concludes the novel. Yap’s heroic story, akin to The Odyssey or The Epic of Gilgamesh, has been transmitted from one generation of bird to another, until it is eventually translated into English. And while interspecies communication never benefits animals, who have nothing to learn from human beings, it can certainly benefit us, if only we would listen to our fellow species.

The Book of Rain is an essential text for thinking about extinction and environmental catastrophe. It poses existential questions about adaptation and the likelihood of survival on an increasingly fraught planet. While forecasting possible futures, Wharton pauses to look at the wonders of the natural world: the chittering of birds, the beauty of clouds, trees passing messages back and forth, a red-eyed crane staring through a hotel window. In the fable that closes the novel, a goshawk wonders if it would be such a bad thing if all human beings perished. On that question, Wharton suggests that human extinction is an inevitability while holding out the hope of continuing for a while longer.

Allan Hepburn is the James McGill Professor of Twentieth-Century Literature at McGill University.