With Thick Skin, Hilary Peach describes her more than twenty years as an itinerant welder in oil refineries, pulp and paper mills, and shipyards. Since Peach was the rare woman in a male-dominated trade, it is easy to imagine a feminist manifesto. But in fact she describes her experiences — the bad and the good — without making obvious judgments. The memoir is more powerful for this restraint.

In the early 2000s, pressure welders were in high demand, and a good welder was “a star.” If your welding joints consistently passed the X‑ray tests that ensured they would hold, “you got the best jobs, all the overtime, better hotel rooms, overcooked steak dinners with the boss at Moxy’s, served by underage girls in short skirts.” Pressure welders who pulled so‑called travel cards —“When a boilermaker local is short-handed they will put a call out to the locals in other regions looking for union people to fill the positions”— could earn enough in three months to pay off a truck or take a trip to Hawai‘i.

At the beginning of her career, Peach knew how to stick weld, “the most common process in the industry.” To learn the more complex and better-paying TIG welding — short for “tungsten inert gas”— Peach trained with a man named Denby. As she picked up the technique, he stopped teaching conventionally, and they communicated instead by trading lines from Bob Dylan songs. When he felt she had practised enough for her first pressure welding job, he said, “Nobody ever taught you how to live out on the street so now you’re just going to have to get used to it,” quoting from “Like a Rolling Stone.” Peach paid $1,500 for a plane ticket to Montana, knowing that if she failed her test, she would immediately be sent back to British Columbia.

In the airport in Vancouver, an American customs official insisted that Peach was trying to travel illegally on her boyfriend’s papers, unable to grasp that a woman could be a boilermaker. Peach was eventually allowed through when the first agent’s supervisor gave his approval, noting, “My daughter wants to be a welder.” At the plant, a guy called Weasel tried to sabotage Peach’s test. She was saved only by her own bravado and her judicious use of the word “horseshit,” an expletive that “cowboys understood, serious enough that they wouldn’t use it at home or in front of a lady, but not so fierce that I would offend my male bosses completely.” Against protocol, she won the chance to repair her test and got the job.

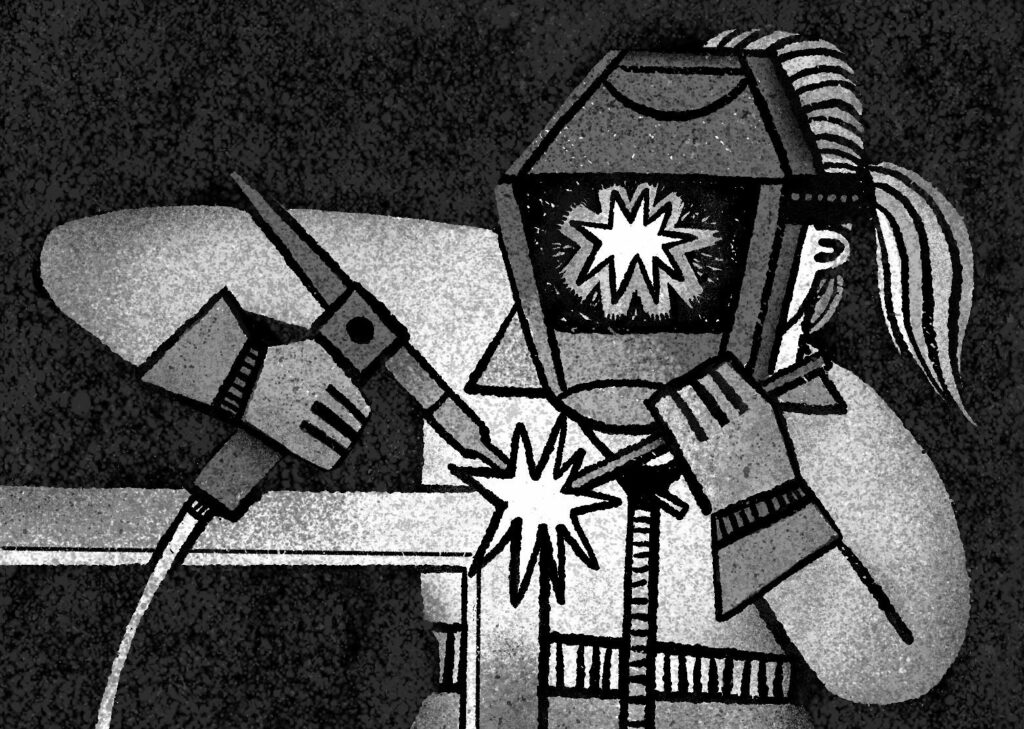

The rare woman in a male-dominated trade shares her story.

Sandi Falconer

Over more than two decades, Peach travelled across North America to weld, performing a trade that was both absorbing and challenging. “You have to get the amperage just right, and the rod angle, and you have to weld fast,” she says of working with stainless steel at a Canexus chemical plant in North Vancouver. “The slag forms a solid crust over the bead and will suddenly crack and fly off as the weld cools, burning the welder, sticking to her skin. But if you’re good at it the result is a flawless, flat, shiny weld.”

In her early jobs, Peach talked through each assignment with her welding partners, figuring out the best plan of attack. By the end, she had become so expert that she proceeded wordlessly and efficiently, already knowing what to do.

The work often took her to small towns. At a power plant in Montana, she was fascinated by tumbleweeds, collecting them on the porch like artwork. She welded together giant combustion ducts in Pennsylvania, where her partner, Durland, was “a giant of a man, tall and broad.” On their first day together, he swore to her, “If you’re my buddy, I’ll die for you. And we will go together.” (His oath was a reminder of the ever-present dangers of the job and the power of the welding brotherhood.) At the Nanticoke refinery near Hamilton, Ontario, she was ostracized by a family of francophone welders while they worked together on high towers in freezing weather. Eventually, she earned their laughter and affection after spending weeks setting up an elaborate dirty joke, which involved a striptease and an imaginary tattoo. She took a job in Fort McMurray, Alberta, where, like the rest of the workforce, she was soon coughing and hacking because of the pollution from a nearby refinery. An “unnervingly handsome” physician barely examined her before announcing, “Congratulations, you have the Syncrude flu.”

Difficult conditions were often compounded by long hours, night shifts, and few days off. Many jobs were dangerous because Peach was being tested as a new female worker or because safety was not a priority on the site. She describes the more routine dangers matter-of-factly, as well as her own resigned anticipation of sexist jokes. “Some hot slag fell into my jacket and burned my chest,” she once wrote in her journal. “Quick thinking apprentice soaked me with water from the squirt can. Expected wet T‑shirt jokes but there were none, just kudos to him for putting out the fire. He saved my skin.”

Several weeks into another job, Peach developed extreme dehydration that led to an injury. She was told to take a week off but negotiated it down to two days. Once again, her co-workers stepped in. Every time she opened her door, there was a bottle of orange juice or Gatorade in the hallway, left anonymously.

There were other satisfactions amid the hardships and the dangers. On a high-risk job dismantling scaffolding, where any dropped object could result in injury or death, she put in back-to-back ten- and thirteen-hour days. “I had never felt so tired, or so strong.”

Living conditions at work camps varied widely. Often, they were small and dirty. “There was a tiny bed, slightly larger than a camp cot, with an itchy wool blanket and a thin, plaid bedspread, and faded yellow linoleum on the floor,” she writes of spartan female quarters in Fort McMurray. “There was a very small table in the corner beside the door, with a bare lightbulb over it, and a mirror and a towel rack, and a shelf and a soap dish bolted to the wall, but no soap in it, and no sink and no water.”

When camps were unavailable, Peach made do with what she could find. Once in Montana, she ended up in a house, recommended by a local, “full of guns and dead animals.” More troubling, there were “axe holes the size of my head in my bedroom door.” After three nights alone, and facing the prospect of the owner’s return after a “dry‑out,” she took her co-worker’s advice “to get the hell out of Dodge.”

Occasionally, Peach was lucky, as when she spent five weeks at the Green Dragon Organic Farm and B & B, in Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia. The owner kept goats, geese, and ducks and did photography on the side. He agreed to a weekly rate, space in the fridge, and her own bathroom. “Within a week we were dining together,” Peach writes, “and spending a couple hours each evening swapping websites about interesting things.”

Because jobs in unfamiliar towns and cities could last weeks and often months, homesickness was a fact of life. Peach invented rituals for herself, watching the same television shows or eating the same foods after each shift. “I kept myself sewn inside a routine of small movements,” she writes. She befriended animals, too. There was a dog who walked with her out into the dusty landscapes of rural Montana. She rescued another, maybe part wolf, from the roadside near Mackenzie, British Columbia. She fed him, coaxed him into her car, and then drove him to the nearest town, where she located his owner.

If homesickness was a reality Peach shared with her male colleagues, other experiences were specific to her as a female welder (if not unknown to women in other workplaces). A man named Bo, for example, kept up a steady stream of obscenities at lunch hour, targeting her specifically. Peach went from fear to rage to a wary acceptance, eventually meeting Bo’s language with her own frank expressions of disgust. Still, many of Peach’s colleagues were on her side when another man sent her a Polaroid of himself holding his erect penis, with the caption “Here’s a taste.” They were shocked by the photograph, and when she decided not to file a formal complaint, they quietly ensured that she was accompanied everywhere, on and off the site.

Peach herself was not above intimidation tactics, if only by proxy. “He was a psychopath,” she says of Bo, “but he was our psychopath.” When she faced harassment from men in other trades, Peach recruited Bo for her own purposes. He obliged, targeting her harassers. He was laid off the next day, though he would later assure her, “The pleasure was all mine.” In describing these moments, Peach neither emphasizes nor downplays the singularity of her experience. Nor does she fall into easy pronouncements, despite her directness in describing the “toxic masculinity” of some.

If Thick Skin makes it clear that women face specific kinds of harassment, Peach is equally concerned for the men in the welding profession, who suffer from many hidden injuries. Over the years, she lost too many co-workers to accidents, overdoses, and suicide: “It’s ironic that the most stressful, the most dangerous jobs, the ones with the longest hours and most extreme conditions, where people are separated from their families and support systems, are the same jobs that teach us not to show how we feel.”

Reflecting on her time in the boilermakers’ union, Peach calls for more equality, but her concern is broader than the fate of other female welders. She hopes for a profession with greater compassion for human vulnerabilities: “A little more understanding that we all have our limits, our soft spots, the places where the knife can go too deep.”

In the current moment, we are often quick to judge and eager to declare where we stand in the culture wars. We are expected to take sides, especially on social media, and the university where I teach is no different. Classrooms are polarized spaces where students state their politics from the start, rather than first giving themselves or others space to think.

This book could have been a simple denunciation of misogyny and not much more. But Peach, who left the trade in her early fifties to become a welding inspector and safety officer, offers a salutary reminder that there is another way. She is frank about the difficulties, unfairness, and dangers of being a woman in her former profession, while asking for empathy —“a little more tenderness”— for all those whose work demands that they have “thick skin” and who then pay the price for that toughness.

We would be better off if we resisted quick judgments and heeded Peach’s call for compassion in our pursuit of social change. At the very least, we can learn from this well-written, absorbing, and often moving memoir.

Elaine Coburn is an associate professor of international studies at York University.