Whit Fraser opens True North Rising with the 1970 trial of an Inuk man. Adam Tootalik, the accused, listened — confused, maybe terrified — as lawyers debated in a foreign language whether he had broken a law he never knew existed. The seasoned hunter had been party to the killing of three polar bears, including a large female. Under a recently passed Northwest Territories game ordinance, he was charged, in effect, “with practising the ancient skill that had allowed Inuit to survive for thousands of years.” He was one of many Arctic residents, living in relatively new communities like Spence Bay (now Taloyoak), who found themselves “in a kind of legal twilight zone, where the white man’s rules had to be obeyed.”

While on his way to cover the proceedings for CBC Northern Service, Fraser watched from the cabin of a Douglas DC‑3 as the trees below gave way to a vast expanse. He spotted a black dot against the snow — a hunter navigating what looked to the untrained eye like a homogeneous pattern of rolling hills. “On any other day,” Fraser muses, “it could have been Tootalik.” With that image, the author captures the North, its people, their traditions, and the many challenges they continue to face.

Two years prior, in 1968, Pierre Trudeau had appointed Jean Chrétien as Indian affairs and northern development minister. “That title — those two tasks on the same business card — tells us everything we need to know about the political push that led to the boom in northern resource development,” Fraser explains. “Chrétien’s marching orders were clear. Manage Indian affairs but, above all, develop the North.” At the Elks Hall, which housed the legislative assembly in Yellowknife, Fraser had watched the federal minister commit to building gas and oil infrastructure along the Mackenzie Valley. By 1973, Canadian Arctic Gas had proposed a multi-billion-dollar pipeline that would extend 4,000 kilometres from Alaska to Alberta. Some Dene, Métis, and Inuit, as well as environmental lobbyists, protested the project, and the Liberal government, which had fallen in the polls, called on a young British Columbia judge, Thomas Berger, to investigate the impacts of the proposal.

The Berger Inquiry, a focal point of Fraser’s career and of his book, took place in thirty‑five communities between April 1975 and November 1976. The journalist recounts those times through anecdotes of travelling with his broadcast team. They reported from smoke-filled community halls and produced radio coverage in Chipewyan, Dogrib, North and South Slavey, Gwich’in, Eastern and Western Inuktitut, and English. They watched an airplane carrying Berger and his staff touch down after it had “laboured over the rock-riddled half-field, half‑bog” of Trout Lake (now Sambaa K’e), a small community in the Northwest Territories with no real landing facility. They grew as reporters and as friends. Most impressive in this retelling is Fraser’s deployment of powerful quotes from such Indigenous leaders as Frank T’Seleie of Fort Good Hope First Nation: “My nation will stop the pipeline. It is so that [an] unborn child can know the freedom of this land that I am willing to lay down my life.”

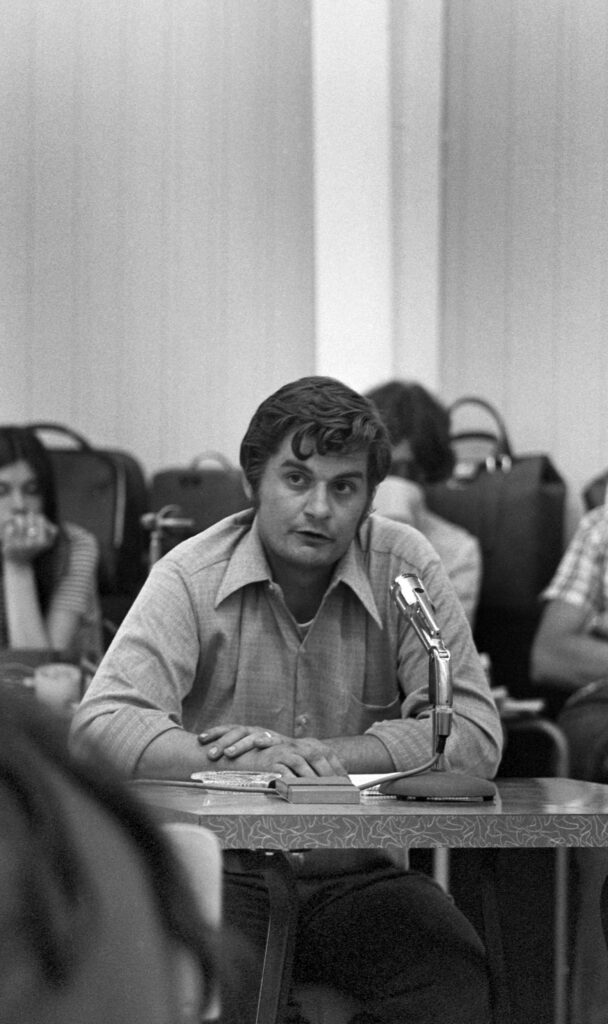

Covering the Berger Inquiry, in August 1975.

NWT Archives; Native Communications Society; Native Press photo; N-2018-010-01234

Fraser has had an impressive career, but the appointment of his wife, Mary Simon, as governor general in 2021 gave his name even wider exposure. To his credit, he recognizes the responsibilities his current role entails. “Mary’s priority is my priority,” he writes. “To the extent that the spouse of a governor general has political capital, influence and opportunity to bring about change, I will use mine in the same way.” A few chapters are dedicated to Simon, their partnership, and her evolution from the “Winsome Little Miss” portrayed on a 1952 Hudson’s Bay Company magazine cover to the federal viceroy who told Justin Trudeau on a national broadcast that her Inuit name, Ningiukudluk, translates to “bossy old woman.”

Simon’s status wasn’t always recognized. In her Truth and Reconciliation Commission testimony, she noted that while growing up in Kuujjuaq, in Northern Quebec, she didn’t attend residential school: “For the government administrators in that time and that place, I just wasn’t Inuk enough.” Although she stayed with her family, she endured survivor’s guilt, having seen “the despair of fathers with no sons to hunt with, mothers with no daughters to sew with, and grandmothers with no children to tell stories to.”

It’s been twenty-five years since the TRC was established and a half-century since the Berger Inquiry, but past injustices persist. In 2021, a hunter stood up at a review hearing for a mining expansion on North Baffin Island and declared, “Our cultures and traditions are not for sale.” This March, two First Nations leaders shouted at Ontario’s premier, Doug Ford, from the visitors’ gallery at Queen’s Park: “No consent, no Ring of Fire.” And as Fraser points out in his postscript, there are a slew of serious issues that didn’t exist before the 1960s. Violent crime rates and suicide among young Inuit are ten times the national average. More than half of northern communities report active cases of tuberculosis — a disease practically eradicated in the rest of the country. Climate change, water contamination, and melting ice are damaging the land. At a time when the federal government affirms truth and reconciliation as a national priority — while simultaneously militarizing the Arctic and updating its critical minerals plan — True North Rising reminds us what and who must be involved in consultation and decision making.

Fifty-three years ago, the N.W.T. Territorial Court convened at the Spence Bay schoolhouse. Tootalik’s lawyer, Mark de Weerdt, argued that his client had shot the bear “on the sea ice beyond Canada’s three-mile coastal jurisdiction limit” and Canadian sovereignty didn’t extend that far. The court’s chief justice, William Morrow, was unconvinced. He convicted Tootalik and ordered that the polar bear hides be forfeited. When de Weerdt appealed — this time on the basis that the game ordinance wording was ambiguous — the decision was overturned by another judge, Harry Maddison. Morrow, however, wanted to commemorate the case he’d heard, so he commissioned the artist Abraham Kingmiaqtuq to carve a likeness of Tootalik aiming a gun at three bears. The piece is now part of the Sissons-Morrow collection, maintained by the N.W.T. Department of Justice.

David Venn is an associate editor with the magazine. Previously, he reported for Nunatsiaq News from Iqaluit.