Spanning India, Kenya, Uganda, England, and Canada, Janika Oza’s debut novel, A History of Burning, charts the lives of ten characters across four generations of an Indo-Ugandan family. The first section, dated 1898 to 1958, opens with Pirbhai at age thirteen, an “oldest son, no longer a boy,” in the western Indian state of Gujarat. When his mother sends him out in search of work — the family have little to eat, and his middle sister is seriously ill — he is tricked into bondage by a merchant. Lured by a weighty coin pressed into his palm and the promise of employment, Pirbhai seals his fate by placing an inky thumbprint on a contract he cannot read. That same evening, he boards a dhow with other vulnerable boys and men, their destination unknown. After months at sea under terrible conditions, the boat docks at Mombasa, Kenya. There he learns he is to build a railway to Lake Victoria, in Uganda.

Pirbhai has left Gujarat without saying goodbye to his family. Although he vows to return — he will “work the hardest” to “atone for his absence” and for the “pain his leaving had caused” his mother — his hope is soon crushed by grinding labour. Pirbhai’s is the first in a series of shattering separations that punctuate this novel, which maps his family’s experience of dispossession and disruption, exile and relocation.

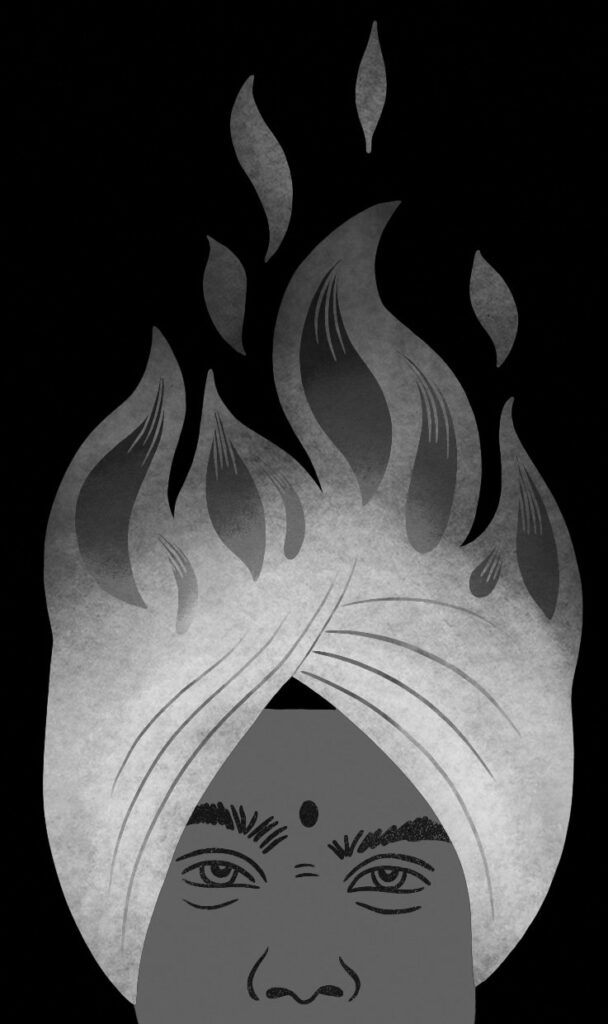

A grievous episode links Pirbhai to the burning of the book’s title, as he is required by the overseeing British colonel to incinerate a village that lies in the path of the proposed railway line. Although the cluster of small round huts summons a vision of his loved ones, Pirbhai carries out the “bloody deed,” believing that his survival depends on his loyal servitude. “The dry thatching snapped into flames” as if his own home were alight. For the rest of his life, he bears “the dark burden” of guilt for what he has done.

A few years later, Pirbhai and his bride, Sonal, depart Kenya and settle in Kampala, where Pirbhai helps run a pharmacy owned by Sonal’s cousins. They raise their daughters and son, Vinod, in relative comfort, but as Indians in Uganda they confront racism and live with economic and professional restrictions.

A polished debut by a gifted storyteller.

Jamie Bennett

Pirbhai and his growing family suffer the fallout of colonial rule and politicized terror. In 1947, Vinod’s fiancée, Rajni, arrives in Kampala from Karachi. Her arranged marriage has saved her, providing an escape from the violence of Partition, but her two young brothers are killed. Rajni and her parents never recover from the catastrophe. Their connection is severed, and the family unit is ruptured permanently.

The novel’s second part covers the years 1962 to 1972 and focuses on Latika, Mayuri, and Kiya, the daughters of Rajni and Vinod, who come of age during the rise of the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin. Latika is a journalist and political activist. She publishes an underground newspaper with her husband, Arun, who is arrested and eventually presumed dead. Kiya becomes a teacher, and Mayuri moves to Bombay, where she trains as a doctor. In 1972, when Amin orders the expulsion of Indians from Uganda, the family are given ninety days to leave. Stripped of their freedom and their possessions, they exit the country in the most dehumanizing and brutal way. For Rajni, this second uprooting is so painful that “the boundaries of her being” calcify; she feels “a part of herself slip from her skin and rise into the bruising sky.” Her daughter Kiya’s molestation by a Ugandan soldier underscores the defencelessness of the Indian minority and the fear and panic they feel under Amin.

At the last minute, Latika makes the dangerous decision to stay behind in Kampala to search for Arun, handing over her infant son, Hari, to the care of her mother. The book’s third section, dated 1974 to 1992, follows Rajni, Vinod, Kiya, and Hari to Ontario, where they settle in Toronto and struggle to integrate, having brought with them the enduring memory of loss as well as the truth of Hari’s parentage. Despite the great hardship of having to start over a third time, the new city affords Rajni the stability she craves. She and Vinod finally accept that “home found them” in Canada.

That sense of shelter might be what steadies Rajni when she learns that Latika is alive and has been living in London for decades. It is also what propels the story toward a new openness. When two of the youngest members of this generational saga, Hari and his aunt Kiya, demand to know the truth, they bring their elders to see the wisdom of sharing a family history that is both cruel and agonizing.

Rajni and Vinod might find refuge in Canada, while Kiya, Hari, and eventually Mayuri might find a promising future. But as if recognizing that such closure would be too simplistic, Oza shows how the ugly continuum of race-based conflict traverses the globe. In 1992, it reaches Toronto, where people take over Yonge Street in response to the killing of Raymond Lawrence by two police officers in nearby Peel Region as well as the acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers in the beating of Rodney King. Like his mother before him, who wrote articles denouncing Amin’s racist and treacherous regime, Hari is compelled to join the protest. He becomes part of “a collective, a movement against history, carrying with them not only their pasts and their presents but their insistence on a future.”

Hope for the future is what Oza grants her characters. Indeed, the most striking feature of this narrative is their lack of despair, even when dejection seems warranted. Time and again, they refuse to descend into darkness. Rather, they turn difficulties into opportunities and muster the strength to go on. They do so under dire circumstances that are not of their making or choosing. Buoyed by a vision of the future when they might be able to live freely and securely among family and friends, they cling to the belief that love is “but one long act of forgiveness, of choosing to return, again and again.”

A final reunion, which is neither easy nor redemptive, takes place at the Lake Ontario shore as “waves break and mend, break and mend.” And so the novel closes, with an acknowledgement of the successive displacements that have shaped the lives of Oza’s memorable cast. Over generations, they are persecuted and buffeted by historical events, yet shielded by family.

A History of Burning is a polished work by a gifted storyteller. Janika Oza has succeeded in crafting a tale that is epic in scope and profound in effect, a challenge for even the most seasoned writer and a mark of her early maturity.

Ruth Panofsky teaches English literature at Toronto Metropolitan University. She recently received the Royal Society of Canada’s Lorne Pierce Medal.