In June, the government of Quebec introduced Bill 31, a measure designed to address the province’s housing crisis, marked by low vacancy rates and spiralling rents. To the outrage of affordability advocates, the proposed law would eliminate lease transfers, which allow tenants to pass on their apartments to new occupants for the same rent. (Currently, landlords need a serious reason to refuse a transfer, and they can be challenged in court for doing so.) As it stands, this mechanism acts as a form of rent control, whereby savvy urbanites can find apartments below market rates and dodge the effects of gentrification.

Lease transfers are personally dear to me: one allowed me to secure my 900-square-foot palace of high ceilings and creaking floors, in a triplex near Montreal’s Parc La Fontaine, for $1,200 a month. This admission will probably lose me the sympathy of anyone in Vancouver or Toronto, who might be surprised to hear that transfers exist at all. Certainly, the minister of housing, France-Élaine Duranceau, argues that it is “against common sense” to take so much power away from property owners. But when it comes to social equity, comparative frameworks can be dangerous. Quebec’s students revolted against tuition hikes in 2012 despite paying some of the lowest fees in the country. The fact that Montreal has stronger tenant protections and cheaper housing than other jurisdictions is less cause for complacency and more a warning of how much we stand to lose.

Because gentrification is simultaneously transnational and hyperlocal, it’s hard to know what scale is most effective for discussing it. Too much focus on global trends can make the matter abstract and overwhelming. More specific accounts can lose the bigger picture in favour of technicalities. Leslie Kern’s Gentrification Is Inevitable and Other Lies does an admirable job of toggling between levels of analysis. Kern, a professor at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick, leads with a description of the Junction, a formerly low-income part of Toronto that is now overrun with vegan cafés. “I know it is a cliché to talk about how gritty your neighbourhood once was,” she admits, “but there is a reason why we are all tired of this narrative: so many of our neighbourhoods are being remade before our very eyes.”

From there, Kern expands her scope to other locations in Canada, as well as in the United Kingdom and the United States, with a certain privileging of Chicago. In doing so, she shows theoretical range: Jane Jacobs, the famed defender of New York’s Greenwich Village (and later resident of Toronto’s Annex), appears alongside the Black feminist icon Audre Lorde and the Marxist geographers David Harvey and Neil Smith. But Kern’s great strength is pairing theory with example. Take the Cereal Killer Café in Shoreditch, London, which, in 2014, brought upscaled cornflakes to an impoverished borough and attracted protest and vandalism in the process. Kern uses the café as an entry point to critique the dangers of associating gentrification too closely with the taste of hipsters. Avocado toast may be annoying, and even a coded form of “whiteness,” but “much stronger forces than aesthetic trends” reshape urban areas. The more pressing issue is how “massive, state-sponsored, corporate redevelopment schemes” target certain demographics at the expense of others, with aesthetics as their lure.

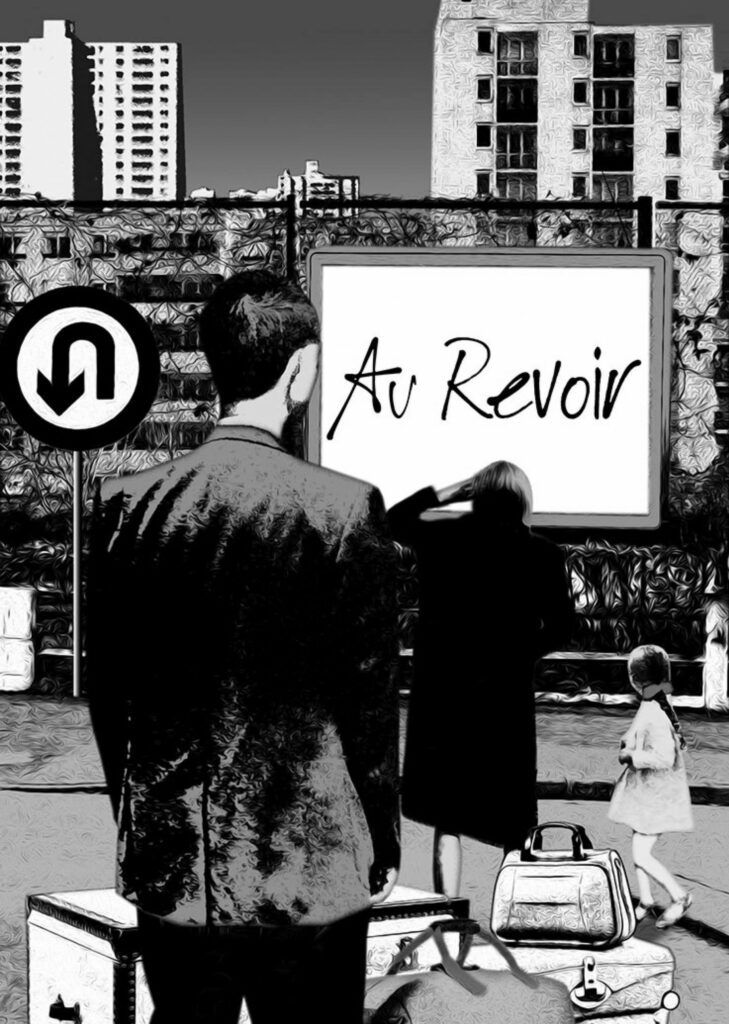

There goes the neighbourhood?

Pierre-Paul Pariseau

Kern’s writing is eloquent and persuasive, and her geographic framework makes the book relevant to a wide swath of readers. Halfway through, however, her central conceit of debunking myths about gentrification begins to wear thin. In her second chapter, she convincingly argues that biological metaphors like “evolution” should be avoided in these discussions, as they portray urban changes as both natural and inevitable. But by the fifth chapter, where Kern argues that gentrification is not exclusively about class, one might wonder if she is over-complicating the matter.

It’s not surprising that Kern would call for an intersectional approach to housing activism; indeed, the move follows dominant academic trends. She argues that “if our frame ignores or minimizes race, sexuality, gender, colonialism, or ability, chances are our solutions will not form adequate barriers against the forces that drive gentrification or protect those vulnerable to displacement.” Yet giving equal weight to all of these factors risks transforming urban affordability into the many-headed Hydra of cumulative social injustice. Of course, racist practices like redlining have shaped urban landscapes, and, yes, mothers are especially vulnerable to eviction. But racism and patriarchy are older problems than spiking housing costs. Do we need to solve the former in order to reel in the latter? There are also particularities to gentrification that cut across ideological lines: the way that the property ladder pitches owners against renters, for example, or the threat that rising prices pose to young families, including the traditional sort. After all of Kern’s layers of theory, one might yearn for the populist wisdom of Jimmy McMillan, who ran long-shot campaigns for political office in New York under a simple slogan: “The rent is too damn high.”

While Kern’s analysis proves portable, I’d hesitate to recommend Gentriville: Comment des quartiers deviennent inabordables (Gentriville: How Neighbourhoods Become Unaffordable) to anyone without a particular interest in Montreal. But what the borough councillor Marie Sterlin and the journalist Antoine Trussart lose in breadth, they gain in depth, particularly when it comes to history.

Most discussions of gentrification begin in the mid- or late twentieth century. (The term did not even exist until 1964, when Ruth Glass coined it to describe the London borough of Islington.) Refreshingly, Sterlin and Trussart go back much further, tracing the development of Montreal’s housing stock from the nineteenth century. Their first chapter outlines the city’s construction boom between 1852 and 1929, when developers following tramway lines built duplexes and triplexes in what the authors dub a form of urban sprawl. Unlike those responsible for condo megaprojects today, these entrepreneurs usually had only a handful of properties to their name, so their holdings kept some architectural diversity on Montreal’s streets. Nevertheless, their choices still “depended on the potential profitability of projects” rather than “the needs of families.” Many of the city’s vaunted qualities — its gentle density, the relative abundance of rental units, the charm of its wrought iron and stained glass — are thus the lucky side effects of an earlier generation’s attempts to make some cash.

This historical perspective creates a pervasive sense of déjà vu. When Sterlin and Trussart note that the landowners who most benefited from Montreal’s expansion were often elected officials, one hears the echo of the Charbonneau Commission’s findings in 2015, about corruption in the construction industry. And they compare contemporary displacement due to rising rents to the urban renewal projects of the 1950s and ’60s, which razed entire blocks. Although this long view is compelling, its practical implications are not always clear. By accounting for the postwar decline of central neighbourhoods, the authors end up highlighting the positive effects of gentrification, as the middle-class attraction to historical authenticity became a “blessing for the preservation of the built environment.”

Unfortunately, the past does not seem to offer many solutions to the current crisis. Indeed, Sterlin and Trussart suggest that the usual proposals — more co-ops, additional social housing, penalties for speculation — may not be enough. Instead, we need to rethink our relationship to property altogether. Rather than treating houses like investments, we should regard them as more like vehicles: something we buy in order to use, even if their value declines with time. “Doesn’t a house already bring us enough,” Sterlin and Trussart ask, “without us expecting that it will also bring us money?”

Where Kern’s work is intersectional to a fault, Gentriville is surprisingly silent on issues of race and ethnicity (Sterlin, incidentally, is of Haitian descent). The omission is striking in the book’s discussion of Parc Ex, one of the city’s poorest neighbourhoods and a hub for the South Asian community, which is now under pressure due to the construction of a new Université de Montréal campus nearby. Sterlin and Trussart highlight the university’s failure to respond to calls for student housing that might limit gentrification, but they barely acknowledge how the cultural composition of the area stands to shift. One wonders if the silence is strategic. Given the politicization of immigration by two of Quebec’s major political parties and the media panic over residents who don’t speak French at home, questions of cultural identity may take over the conversation if let into the frame.

Tracing the hip restaurants and corporate headquarters that have changed places like Mile End, Gentriville is rich in detail. With Deindustrializing Montreal: Entangled Histories of Race, Residence, and Class, Steven High takes this commitment to the specific one step further. His sumptuous tome is dedicated to just two neighbourhoods: Point Saint-Charles and Little Burgundy, formerly industrial areas that face each other across the once polluted, now desirable Lachine Canal. This choice is not impartial, as the Concordia professor lives in the Point. Still, the juxtaposition remains fruitful.

Traditionally white, working-class, and bilingual, Point Saint-Charles suffered through factory closures and urban decay during the 1970s and ’80s, while developing a celebrated activist culture. On the other side of the canal, multiracial Little Burgundy has long been a hub for the anglophone Black community, with residents like the jazz great Oscar Peterson and Malcolm X’s mother, Louise Little. The neighbourhood was targeted for urban renewal in the ’60s, losing streets and population to a highway.

As his title suggests, High aims to “find ways of thinking about race and class together without submerging one or the other.” His book relies on extensive and varied oral histories, many of them involving “stories of daring and trespass, fisticuffs and bravado.” High handles this material generously; notably, he avoids dismissing working-class white men as toxic or problematic, even as he highlights how gender and race shape their accounts. He also documents how Black residents were largely frozen out of factory employment, with women often working as domestics and men as train porters. (His material on porters’ unions is a welcome companion to other recent works, including Cecil Foster’s They Call Me George, Suzette Mayr’s The Sleeping Car Porter, and the CBC’s The Porter.)

As a study of displacement, High’s book contains two big surprises. First, he finds “no clear evidence that Little Burgundy was explicitly targeted for urban renewal because it was the historic home of Black Montrealers,” who made up about 15 percent of the population in the ’60s. This demographic still paid the price, however, and the area’s “growing reputation as a racialized ghetto” in the aftermath “led the city to prioritize it for gentrification.” Second, High critiques the romantic narrative of community activism in Point Saint-Charles, often celebrated as the site of Quebec’s first community health clinic and housing co-operative. The historian balances these accomplishments with a description of botched projects to argue that neighbourhood activists “utterly failed to protect those most vulnerable to economic and urban change.”

Ultimately, academic interventions seem secondary to High’s project, which is above all a deluxe love letter to two neighbourhoods and their residents. The book is filled with colour photographs, and the extensive interviews and archival detail testify to High’s diligence, as well as to his access to academic grants and graduate research assistants. This is not necessarily a criticism. High is known locally as a public-facing scholar, who conducts walking tours, writes op-eds, and organizes off-campus events. His work is the kind of deeply humanist tribute that all neighbourhoods deserve but that few receive.

Housing is a visceral subject, given how deeply it structures our everyday lives. I have no reason to think my landlord — who is “the good kind,” a retired woman who lives in the apartment below me and raises the rent slowly — plans to evict me any time soon. But even her most casual reference to potential renovations lands like an existential threat. Quebec’s housing minister, herself a former real estate broker, would respond that renters like me “should invest in housing and accept the risks that go with it.”

When the news broke that Minister Duranceau had been involved in a flip in 2019, in which investors bought a Montreal duplex for $500,000 and resold the building as condos for $3 million, I found myself electric with rage. I can hardly imagine how I’d feel if I were precariously employed rather than just priced out of ownership. Sterlin and Trussart lament that, despite thirty years of swelling wait-lists for social housing, the affordability crisis enters the political agenda only “when it is middle-class people who start to be affected by the problem at a national scale.” They imply that this moment has already arrived in Quebec. When I think of Vancouver and Toronto, I dread how much worse the situation might still become.

Amanda Perry teaches literature at Champlain College Saint-Lambert and Concordia University.