A decade ago, when Statistics Canada surveyed adults on literacy levels, the findings were perplexing. Despite our high education rates, nearly half of participants couldn’t “identify, interpret, or evaluate one or more pieces of information.” Nor could they “disregard irrelevant or inappropriate content.” Many struggled even to read news articles and fill out job applications.

The situation hasn’t exactly improved. As Michael Burt, an economist with the Conference Board of Canada, pointed out in a CBC interview two years ago, many employers in our resource-based economy simply don’t place much value on their employees’ reading or writing skills. Those who occupy high-risk, low-mobility positions in industries like forestry and mining often face a double threat: job loss due to automation and a difficult career transition due to low literacy. It’s been this way for a long time. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for example, people working in railway, lumber, and mining camps often missed out on educational opportunities — an injustice Alfred Fitzpatrick sought to redress by founding Frontier College.

As James H. Morrison recounts in The Right to Read, Fitzpatrick was the grandson of Scottish and Irish immigrants who had laboured to “clear, settle, plant, and survive” in northern Nova Scotia. Solid religious education had sustained those early endeavours, but as the population matured, tensions arose between conservative and progressive church denominations. In 1864 — just two years after Alfred was born — the colonial legislature passed the Free School Act and laid the groundwork for non-sectarian public schools. Morrison, a historian and former Frontier College instructor, quotes Robert Burns to capture the spirit of the times: “Here’s freedom to him that wad read, / Here’s freedom to them that wad write.”

Fitzpatrick had the good fortune to grow up in a town that boasted a Literary and Scientific Society, a Philharmonic Society, and the second-highest number of booksellers in Nova Scotia after Halifax. Perhaps that’s why he became an accredited teacher and then a minister. But the young man from Pictou made his greatest mark on the “frontier,” far from the centres of culture and education.

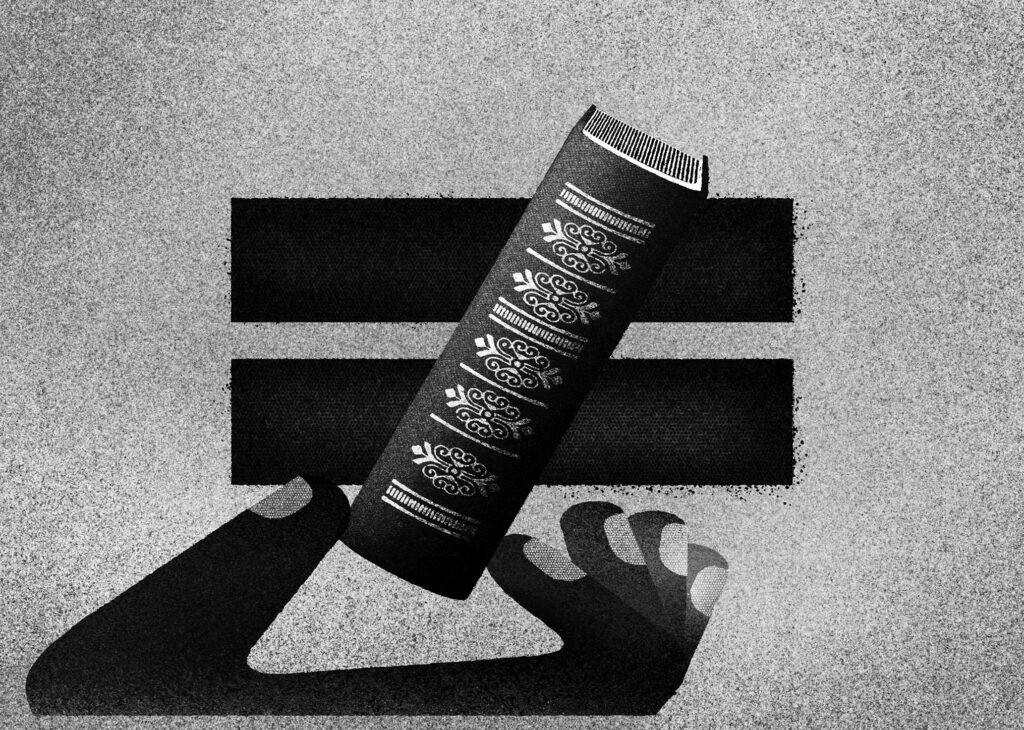

Can everyone reliably benefit from schooling when it’s treated like a commodity?

Karsten Petrat

During his theological studies at Queen’s College at Kingston, in Ontario, Fitzpatrick imbibed a philosophy of constructive idealism. The state, he believed, has a responsibility to provide “the external conditions under which all citizens may have an opportunity of developing the best that is in them.” At the same time, many of Fitzpatrick’s professors and fellow students promoted the social gospel movement, which embodied “a doctrinal shift from saving the individual to a more collective salvation of society by reforming the environment in which the individual lived.” Such ideologies aimed to improve the lives of Canadians and recent immigrants alike.

As a man of the cloth, Fitzpatrick was sent to various places across the country. In 1891, he was posted to Revelstoke, in southeastern British Columbia, where he first met men who worked in “one of the most dangerous jobs in the natural resource industry.” After long days of felling Douglas firs and redwoods, the loggers would retire to “isolated camps of ill-constructed shanties.” The young Presbyterian missionary eventually came to see that the workers’ real needs were medical, social, and educational. Evangelism, no matter how well-intentioned, couldn’t address these. By the turn of the century, Fitzpatrick had abandoned his role in the church in favour of a new “commitment to the almost half-million ‘campmen’ scattered across Canada that he believed had been left out and would soon be left behind unless something was done.”

In 1899, Fitzpatrick arrived in Northern Ontario, where he focused his energies on improving literacy. With support from Richard Harcourt, the provincial education minister, he found tutors to help those who struggled to read. He also set up a “travelling library” system, sourcing books in English, French, and, later, Italian. Contemporary novels, plays, and poetry proved to be the most popular genres, though Fitzpatrick also looked for life writing. (At one point, he tried to obtain a copy of Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery, but he was informed by the renowned author himself that “the supply is exhausted.”)

A few years later, the model was refined further. “As the story is told,” Morrison writes, one of the teachers posted to a woods camp “decided the ‘passive’ library approach was not working.” Rather than sitting around in rooms, waiting for the labourers to come to them, teachers should “work side by side with the men” and become, as Fitzpatrick later put it, “a friend and a brother.” Thus was born the raison d’être of the Reading Camp Association, which in 1919 was renamed Frontier College.

In researching his book, Morrison combed through collections from diverse repositories, including archives of the Canadian Pacific Railway in Montreal, the United Church in Toronto, and the YMCA in Halifax. He frequently cites Fitzpatrick’s own writing to give a sense of his subject’s dedication to other causes, including environmental conservation as well as workers’, immigrants’, and women’s rights. He describes how Fitzpatrick and Frontier College addressed financial challenges and, in some cases, internecine conflict. And he briefly profiles a handful of former Frontier College teacher-labourers, including the renowned surgeon and early advocate of socialized medicine Norman Bethune and the medical doctor Margaret Strang.

Morrison enlivens The Right to Read with memorable details, like the use of local dialects and vivid landscape descriptions. Another round of editing might have caught some structural infelicities, but the book’s occasional repetition and chronological hopping don’t detract from what is ultimately an inspiring biography. It would have been fascinating to read more about the workers who benefited from Frontier College’s programs, however. Late last year, the organization was renamed United for Literacy, “reflecting the ambitious next chapter in its history,” according to its website. Perhaps that next chapter will highlight some of those stories.

Fitzpatrick and his colleagues believed governments have a duty to ensure ongoing access to education for people of all ages and classes. Policy changes over the last several decades, however, have effectively shifted much of that responsibility to the private sector and to individuals — including parents. Underlying this devolution is the increasingly popular view of education as a commodity.

Sue Winton’s Unequal Benefits is a work of public scholarship complete with an introduction to critical policy research. The short volume outlines many of the ways in which primary and secondary schooling has been subjected to privatization. The ramifications of this change, Winton convincingly argues, go beyond childhood and the individual student. Her intended audience includes parents and politicians, as well as “members of the general public interested in understanding how certain education policies contribute to social inequalities.”

In her opening chapter, the York University education professor states her support for the ideals of critical democracy, including “equity, inclusion, social justice, diversity, public participation in decision-making, and the public good.” Public schools, she argues, can advance those aims through what gets taught (we see this in decisions about curriculum on Indigenous histories, for example). But “students’ observances and daily practices” are equally important. In other words, if the system doesn’t practise what it teaches, there’s something wrong.

Winton contends, surprisingly, that high levels of support for public schooling in Canada persist, despite a slight downward trend, in part “because public systems have become more private‑like.” Decreased government spending, increased reliance on local fundraising efforts, the development of specialized programs that aren’t accessible to everyone (like French immersion), and partnerships with corporations (such as educational technology companies) are frequently welcomed by parents and policy makers alike as improvements to the basic education on offer. The belief that “the private sector is more efficient than the public sector because of businesses’ need to compete for success” has gained particular traction. “Understandably,” Winton writes, “most parents will do whatever they can to help their children be successful in a competitive market.”

The advent of public schools in the nineteenth century was one response to major social changes, including industrialization, population growth, and increased poverty. Winton reminds us that those institutions were meant to “serve the public as well as individual children and their families.” The latter goal is as alive as it ever was, but we seem to have given up on the former. Though Winton never comes out and says it, she suggests that most of us follow a kind of Randian model of rational selfishness: there may be some ultimate benefit to society, but if there is, it’s incidental. And if there is none, at least my child is doing well. Such me‑and‑mine‑first thinking is particularly apparent in the way we deal with international students.

In Fitzpatrick’s time, immigrants were often impoverished and underserved. They were valued, primarily, as cheap labour. Today, students from other countries — whether they attend universities or even public primary schools — are valued as a source of revenue because they pay (often exorbitant) tuition fees. “I’ve yet to find a government scholarship generous enough to enable young people from a wide range of countries and social classes to attend Canadian elementary or secondary schools,” Winton notes. Many of these temporary residents return to their home countries where they are “more likely to obtain employment than their locally educated peers.” Nowhere does an interest in the public good — whether that of Canada or another country’s — seem to factor into decisions around admission and enrolment. Rather, these students continue to “reproduce their own class advantage,” which in turn “facilitates inequality on a global scale.”

I do wonder if Winton isn’t preaching to the choir, despite her desire to reach the broader public. I find her arguments convincing, but I also accept the ideological premise. For those who ardently believe their children’s competitiveness in the future job market is more important than some vague social good, Unequal Benefits might not make much of an impression. To do that, Winton would have to engage in a lengthy philosophical debate, which would mean writing a very different book.

In The Philosophy of Money, his magnum opus from 1900, the German sociologist Georg Simmel wrote that the “apparent equality with which educational materials are available to everyone interested in them is, in reality, a sheer mockery.” His point wasn’t to say universal access is impossible, but he was careful to observe that, all too often, our “liberal doctrines” fail to acknowledge “the fact that only those already privileged in some way or another” can reliably benefit from education when it’s treated like a commodity.

Statistics Canada is scheduled to release updated literacy findings in 2024, and it will certainly be interesting to see if we fare any better than we did ten years ago. But if Simmel is right — if education is still understood as something to be bought and sold in a competitive market rather than as a human right worth protecting and even cultivating — then I doubt much will have changed. And if that’s the case, we’ll still have a long way to go before realizing Fitzpatrick’s and Winton’s ambitions.

Marlo Alexandra Burks is the author of Aesthetic Dilemmas and a former editor with the magazine.