In 1974, thirteen-year-old Janice Derbyshire was raped by a group of seventeen- and eighteen-year-old boys in a pickup truck. No one came to help her. She was left “dishevelled and confused” behind a “faded-green grain elevator in southern Alberta.” Twenty-eight years later, Janice is no longer Janice. They are Joshua Dandelion, or JD, a “genderqueer, lesbian woboy who can make the sun stop in its tracks and is seen as a weed but has incredibly useful properties.” They are also hearing voices, barely clinging to sobriety, and relying on a convoluted cocktail of prescription drugs to deal with the traumatic memory that threatens to crush them. This all makes for an “emergency”— an anagram of which gives the Vancouver-based comedian and playwright JD Derbyshire the title of their debut novel.

Adapted from Certified, their participatory stage show, Mercy Gene is a form-defying work of autofiction consisting of “fragments that come out of order, unruly, sudden, begging to be seen.” It includes lists, epistles, monologues, dialogues, first-person anecdotes, second-person addresses, and sustained meditations on gender expression and tolerance. Derbyshire does not so much recount their life story as they invoke an array of writing styles meant to represent their range of emotions. In this way, they keep the line between their inner, subjective world and the outer, objective world blurry throughout the novel.

Central to the story is their sexual assault. Derbyshire’s difficult yet necessary return to the incident takes diverse shapes, from a comprehensive digression on the history of grain elevators to a series of imagined — yet no less agonizing — confrontations with their grown-up rapists. It even extends to questioning whether the assault took place. Under the poignant heading “Lament: a passionate expression of grief or sorrow,” Derbyshire admits, “I’m not entirely sure it happened. Maybe I made up everything. I have no solid evidence.” They juxtapose their loss of confidence with a haunting epigraph, pulled from Maggie Nelson’s memoir The Argonauts : “Stories may enable us to live, but they also trap us, bring us spectacular pain.” It becomes clear that Derbyshire’s uncertainty is really wishful thinking. Much of their sorrow stems from the deplorable reality that they could not have made it up — that despite a lack of solid evidence, they are sure it happened. Their assault is undeniably a source of “spectacular pain.” Indeed, they conclude, “Something happened. Something terrible. You don’t know what. You are thirteen years old. There is only an ache that can’t settle anywhere in your body, it just hovers around you, like a bruise in flight.”

Caught up in this seismic event is Derbyshire’s shifting understanding of their gender and sexuality. These developments are traceable through the evolution of their name. “I chopped the ice off Janice in grade nine,” they write. “Everyone was fine with that except my parents and the government.” Their identities are represented by lists interspersed throughout the book. “Janice things” include Dr. Pepper Lip Smacker, a Guy Lafleur poster, and an orange terry towel robe. “Jan things” include a mood ring, some shredded pieces of divorce papers, and three sobriety chips labelled thirty, sixty, and ninety days. “JD things” include a WNBA hoodie, Bronner’s peppermint soap, and Levi’s 501s. Addressing readers who may be confused or even irritated by their progression, Derbyshire stresses the need for tolerance. Acknowledging that “we are in the times we are in” and that they “long to see where this all goes,” they reason that “in the meantime, and it is a mean time, it’s easy to learn someone’s new name and/or pronoun. You don’t have to understand, you can just give a person what they need.”

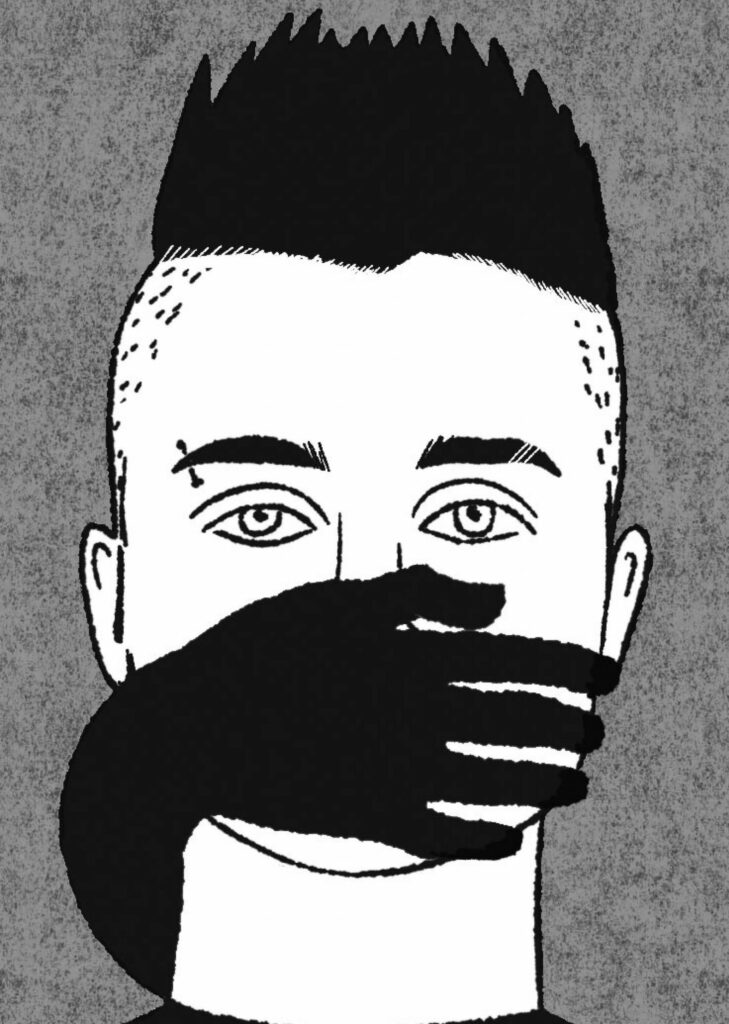

Confronting a source of spectacular pain.

Jamie Bennett

Mercy Gene is at its most compelling when exploring the side effects of Derbyshire’s medical treatment. The author relates how “the voices” arrived in their head shortly after their sexual assault, leading them to contend that the brain is “designed, it seems, to break.” They quip that our grey matter “should be covered in stickers: Fragile, Fragile, Seriously, This Side Up, Really Fucking Fragile!” However, one cannot help but wonder if Derbyshire’s brain is actually “broken” or if it is exhibiting a natural defensive response to acute trauma. This thought occurs to Derbyshire too. “Maybe that’s how the voices came to be,” they speculate, accounting for them as “some hereditary ability, some innate, biologically predetermined mechanism to provide relief from extreme suffering.”

Derbyshire does not tell anyone about their rape or the ensuing voices until the age of forty-one — and, it turns out, with good reason. Following their confession, they are besieged by voyeuristic psychiatrists; overeager diagnoses of ADHD, bipolar disorder, and depression; and a literally dizzying assortment of medications and multiple hospital admissions. When they reject the “straitjacket” of conventional pharmaceuticals and psychiatry, eventually weaning themselves off medication entirely, their writing becomes palpably more joyful. Freewheeling stream-of-consciousness monologues penned during mindfulness sessions meet restorative epistles like “Dear Doctor,” which describe their improved mental health: “I’ve never felt saner, Doc, if sane is some sort of agreement to just stay with yourself and all of your fluctuating moods and tangential thinking and sensitivities.” Through such sober reflections, Derbyshire ably critiques the inhumanity of a health care system that too often construes victims as threats and neuroatypicality as something to be eradicated or ignored.

To be sure, Mercy Gene represents a deeply empathetic response to human suffering. While the book is uneven — a chapter titled “I am a figment of Miriam Toews’s imagination,” in which JD envisions sharing a beer with their fellow novelist, verges on gimmicky — Derbyshire’s autofiction succeeds on the strength of its earnest creativity and profound convictions. It is an exciting, suggestive work of art, bringing readers out to the borderlands of thinking and healing. That it is also a testament to the power of shared storytelling and collective meaning-making is perhaps unsurprising, given the novel’s challenge to the distinction between fact and feeling, its rejection of conventional medicine for more holistic wisdoms, and its origin in interactive theatre. The book begins with a siren: “Me Ma Me Ma Me Ma.” Later, that sound changes: “We Ma We Ma We Ma.” This shift to “we” rather than “me” makes the emergency sound less like a lone plea and more like a rallying cry.

Ellie Eberlee divides her time between Toronto and New York.