Prime ministers can be forgotten. Richard Bedford Bennett governed from 1930 to 1935, and he has been the subject of relatively little scholarly research. Today very few Canadians even recognize his name. William Lyon Mackenzie King, however, has not been forgotten. He usually appears at or very near the top of historians’ rankings of the greatest prime ministers, and he continues to be the subject of book after book.

The two leaders — the forgotten and the remembered — faced off in two elections. Bennett won the first, in 1930, and King won the second, in 1935. That second contest is the subject of David MacKenzie’s King and Chaos, part of UBC Press’s Turning Point Elections series, which has previously published volumes on the elections of 1957 and 1958 and of 1993, both written by political scientists. This book is less committed to theory, has fewer charts, and is more straightforward in its approach. The series editors should be congratulated for asking a historian to write one of their titles.

In the 1930s, Canada was caught in the Great Depression that affected most of the world. International trade collapsed, and nations hiked their tariffs in a beggar-thy-neighbour fashion that hurt everyone. Exports dropped by almost half between 1929 and 1933. The United States, our biggest trading partner, was hit hard, but this country perhaps suffered more. “Everything fell in the Depression,” MacKenzie writes in a clever sentence, “except unemployment, mortgage debt, interest payments, and rain.” In the dust bowl on the prairies, there was not even rain. Prices fell, but so did wages. By 1933, the bottom of the crash, per capita income in Saskatchewan had fallen by 71 percent. The national jobless rate that same year was close to 30 percent, and it remained above 15 percent as late as 1939. There was no unemployment insurance and no social security net; relief payments were tiny, seen as a last resort, and need had to be demonstrated. In Ontario, applicants for relief had to turn in their liquor permits before being considered. Many Canadians seemed to believe that unemployment was the individual’s fault.

Naturally enough, with Canada roiled by fury, unrest, poverty, and hopelessness, new political parties sprang up. In Alberta, the provincial government was captured in August 1935 by the nostrums of Social Credit, offered to radio listeners by the leader of the Prophetic Bible Institute, William Aberhart. Social Credit was difficult to understand, but Bible Bill said there was no need to explain the theory; simply elect the reverend and his candidates and leave it to the “technical experts” to put solutions into practice. That approach worked in the Alberta election (the theory wouldn’t), but would it fly nationally? A federal election had to be held sometime in 1935.

His Liberals leapfrogged the competition.

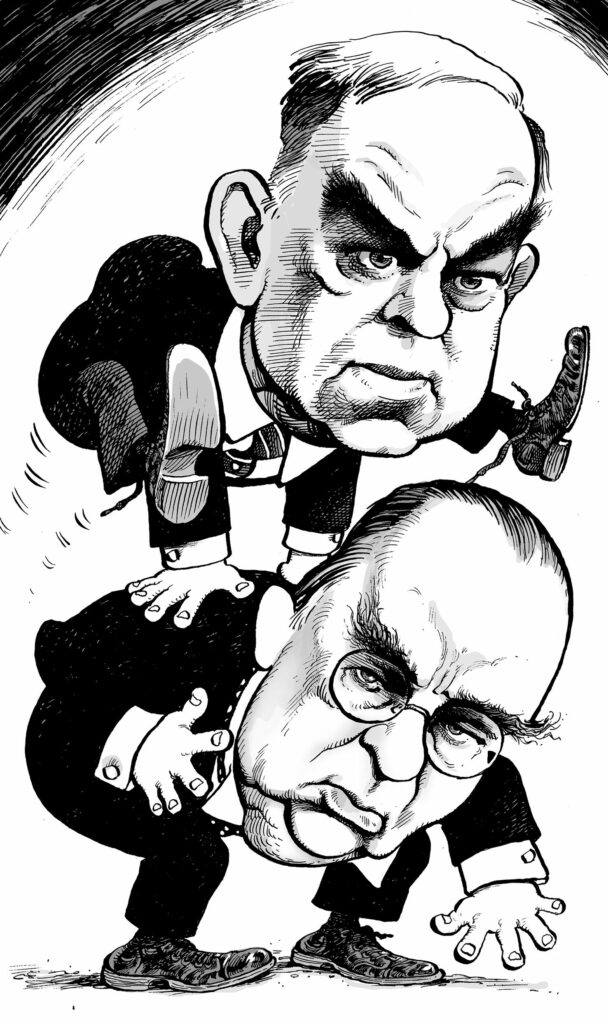

David Parkins

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation was another new party, founded after a gathering of farmers, labour activists, and intellectuals. In July 1933, they produced the Regina Manifesto, which, among its fourteen policy demands, called for the nationalization of banks and railways. As the manifesto declared, “No CCF government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning which will lead to the establishment in Canada of the Co‑operative Commonwealth.” J. S. Woodsworth, another preacher, was the party’s leader and had gathered a few members of Parliament around him. As social democrats, they rejected efforts by the Communists, led by Tim Buck, to run joint candidates.

Bennett, the Conservative prime minister, was hugely unpopular, and many joked that he should never be disturbed when he was by himself because he was holding a cabinet meeting. Hard-working, intelligent, and a bully, Bennett had been baffled by the problems of the Depression, unable to do much more than raise tariffs and promise to “blast” Canada’s exports into global markets, a policy that failed. Under the influence of William Herridge, his brother-in-law and Canada’s minister to the United States, Bennett decided to launch a New Deal in January 1935. This came as a surprise to everyone, including members of his own cabinet. It was also clearly an attempt to emulate Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, but Iron Heel Bennett was no FDR.

In a series of radio speeches, the prime minister laid out plans for several reforms, including unemployment insurance, health insurance, a minimum wage, and price supports for agriculture. His plan was obviously intended as a platform for the coming election, and it sounded good. But the senior members of the Tory cabinet, firmly on the right, were very unhappy.

Mackenzie King, the Liberal leader, was bemused by Bennett. “What a buffoon,” he wrote in his diary. “If the people will ‘fall for’ that kind of thing, there is no saving them.” Nonetheless, King decided that the best tactic would be for his members of Parliament to cooperate with the government, force Bennett to lay out his proposals in detail, and steal his thunder. But then Bennett suffered a heart attack, in March, and was confined to bed in his Château Laurier suite. When he recovered, he went not to the House of Commons but to King George V’s Silver Jubilee celebrations in London. A spring election would not be possible. During Bennett’s long absence, speculation about a change in the Conservative leadership grew.

Harry Stevens had made a name for himself in the trade and commerce portfolio until the fall of 1934, and the speculation focused on him. Representing Kootenay East, he had been a small businessman, a long-time member of Parliament, and a close friend of the prime minister, but the Depression radicalized him and led to a personal crusade against the way big corporations were crushing small business with their profiteering. Bennett had let Stevens run the Royal Commission on Price Spreads and Mass Buying, but Stevens soon was publicly attacking his boss, and relations between the two ended in open hostility. In July 1935, Stevens left the Conservative caucus and began to create his own Reconstruction Party. He had much enthusiasm but no national organization; neither did the CCF or Social Credit.

Meanwhile, King happily watched the Tories disintegrate. The Liberals continued to keep schtum, determined not to allow Bennett to paint them as being against reform. Their platform, such as it was, called for some form of unemployment insurance, a central bank, spending cuts, a balanced budget, and certain tariff reductions. Essentially, King’s policy was to condemn the Tory government for failing to defeat the Depression. Finally, Bennett called the election for Monday, October 14.

The shape of the campaign, set up well in MacKenzie’s chapters, was predictable. Funds were scarce; the Liberals did a little better at securing donations from big business than the Conservatives, while the new parties got little from anyone. Just elected in Alberta, Social Credit ran only forty-six candidates. The CCF ran 121, with none in the Maritimes. The Liberals had strong francophone candidates who promised to secure important cabinet posts if Mackenzie King won. Many Tory members, sensing the public mood, decided not to seek re‑election.

The two old parties leaned heavily on newspaper advertisements, but the editorials in most dailies supported King. Both parties produced radio ads as well. The Tories spent more on radio, featuring Bennett; the Liberals featured both their leader (no great speaker) and other prominent party figures. In movie theatres, the Grits ran ads showcasing Mackenzie King. The 1935 campaign was the first to use the new medium widely, and though its impact was hard to trace, it appeared to matter.

Bennett campaigned across the country. Always wearing a winged collar and sometimes formal attire, he jousted with hecklers. In Victoria, where many in the large crowd jeered him, he unwisely replied, “If you would work your mouth less and your other parts more, you would be better off.” In Hamilton, some in the audience yelled, “You’re through, Bennett!” It seemed to be so.

Mackenzie King also toured the nation, but, unlike the Tories, who had lost most of the provincial governments they held in 1930, the Liberals could also rely on premiers to speechify for him. More important, their organizations were working hard; this mattered in Ontario, Quebec, and the West. King understood that an election is a government’s to lose, and he said as little as possible. “It is only ourselves,” he wrote in his diary, “who can destroy ourselves.” It really did look like it would be “King or Chaos,” as many Liberal election ads proclaimed.

The result was a landslide. With almost 45 percent of the popular vote, the Liberals won 173 seats, plus several seats won by Independent Liberals — the greatest majority to that time. The Conservatives captured only thirty-nine constituencies, while Social Credit secured seventeen: fifteen in Alberta and two in Saskatchewan. The CCF won seven seats: three in British Columbia and two each in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The Communists, running only eleven candidates, drew a mere 20,000 votes, and Harry Stevens’s Reconstruction Party took just under 9 percent of the popular vote, winning only one seat — his own.

King, who had been prime minister twice, was in office again. As H. Blair Neatby, his official biographer, later noted, “If the choice was between King and chaos, more than half the voters had preferred chaos.” Thus the title of MacKenzie’s book.

And indeed chaos soon reigned. Bennett’s New Deal legislation was ruled ultra vires by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. Federal powers, despite the British North America Act, were strictly limited. Alberta was on the verge of bankruptcy, and Quebec tossed out the Liberals and elected Maurice Duplessis, whose primary goal seemed to be to fight Ottawa. Abroad, the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had invaded Ethiopia, and Adolf Hitler’s Germany was rearming. The Depression continued, with unemployment remaining high and recovery slow.

Mackenzie King proved no better than Bennett at fixing Canada’s economy. It took the Second World War to get it going again, and only between 1940 and his retirement in 1948 did King become the leader who, in fact, built a new, stronger Canada. His war and postwar leadership explained why he consistently ranks high with historians.

J. L. Granatstein writes on Canadian political and military history. His many books include Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace.