Tomas Hachard’s debut novel, City in Flames, contemplates the power of those “fickle things” called words: “They can transform while travelling from mouth to ear. They can overflow with meaning or remain hollow.” In a near future, a charismatic politician known as P. rises from city council disrupter in Hillside, a thinly disguised version of Toronto, to populist demagogue across the “nation,” a country fraught with natural disasters, rising living costs, and social inequities. The “eloquent intensity” of P.’s words unites “the West Coast yuppies, the small-towners on the East Coast, the miners and oil barons in the North, the boring bureaucrats in the Capital.” But his control rests on this “smokescreen” of verbal power, and he’s quickly deposed. In the wake of his short-lived tenure emerge “the fires,” a series of anarchic infernos lit by warring citizens of competing political stripes. City in Flames is not only about a politician’s conflagrant rise and fall, however. It’s also a story about modern love.

Sara, a burnt-out graduate student, and Kevin, a languid IT specialist, meet on the dating app Perfect Match. Their usernames reveal much. “QueSaraSara” lives so faithfully by her laissez-faire moniker — a play on “Que será, será,” or “Whatever will be, will be”— that she can barely muster the energy to work on her overdue dissertation about “people who tried to give voice to the voiceless and speak the unspeakable, or some bullshit like that.” And “KVN_07” is about as uncreative as this shorthand for his first name and birth year. After a few days of flirtatious messaging, the pair realize they live an ocean apart — literally. While Kevin has stuck around their native Hillside, Sara’s finishing her degree in London. “If they had noticed immediately,” the fledgling couple agree, “it would have been a mild inconvenience. They would have moved on.” But they’ve become enamoured of each other. The two of them imagine “telling the story of this night several years down the road,” doing their best to ignore the increasingly disquieting signs of P.’s downfall. As borders close and Parliament breaks down, the narrative concerns the questions of when, where, and how these two unlikely protagonists may finally meet in person.

Despite the urgent danger, Kevin, like his dating profile, is “filled with platitudes.” As the fires burn, the apathetic bystander knows “he should feel something,” but he doesn’t: “It was hard to mourn when the buildings seemed to rest easier.” While his incapacity for “fury and fortitude” perturbs his anxious sweetheart, her so‑called activism entails mere lip service. She joins an anti‑P. message board, where, disguised behind a username, she purports to fight anarchy with rousing call-to-action posts, socially conscious GIFs, and thumbs‑up reactions. She even falsifies her participation in a protest at Hillside’s capital by posting attendees’ photos under her handle, receiving undue praise from her online comrades: “When we win this war, it’s going to be because of people like you.”

One of Sara’s instructors, known as “the professor,” considers his student’s behaviour symptomatic of widespread complicity. In the older man’s estimation, the internet is a shield under which too many young people hide: “Back in my day, we went out into the streets. People got hurt. It was painful, but we came together. We supported each other. We fought for what was right.” By contrast, Sara’s generation too often relies not on experience but on words — whether from the government, the news, or each other — to come to grips with reality. But language is not a replacement for action. “You read the same things I do. You know things could get worse, not better,” he intones. “So. Isn’t there something you can do?”

As the fires burn, an online romance simmers.

Gwendoline Le Cunff

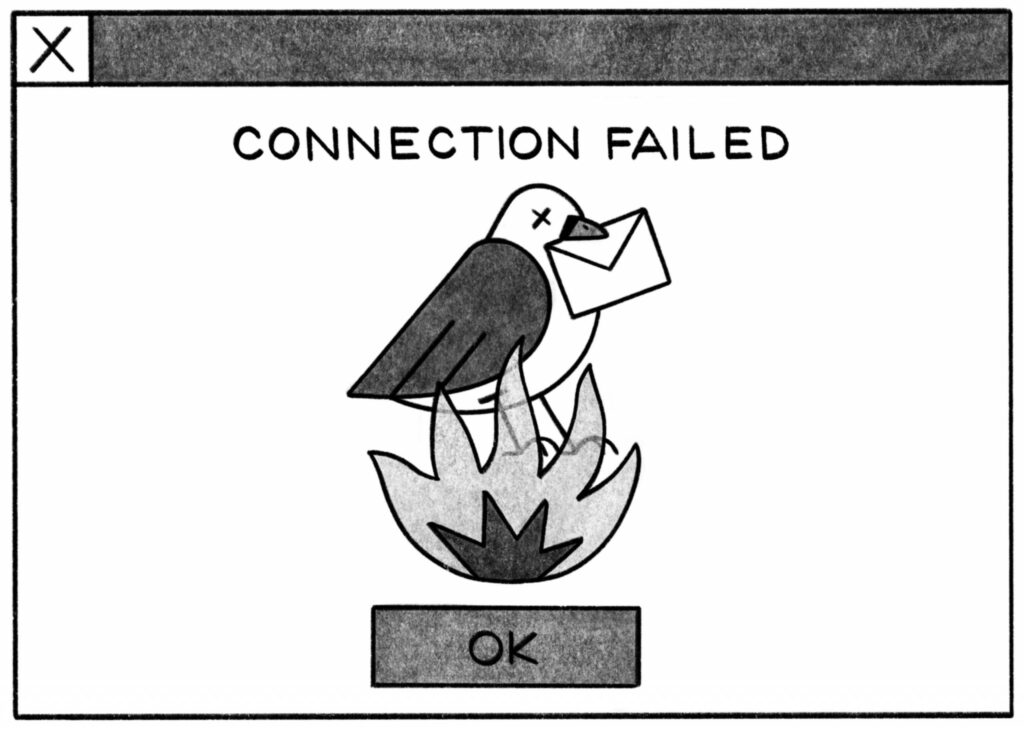

Artfully reflecting this theme, long sprawls of City in Flames unfold through online exchanges between Sara and Kevin. In this way, the plot’s reliance on digital communication mirrors the protagonists’ interdependency. When the nation collapses, causing its citizens to lose internet access, Kevin’s words can no longer reach Sara across the ocean. Readers will feel the vastness of the couple’s separation as the pair struggle to find any way to stay in touch. (“Connection failed” never had such profound meaning.) This unconventional format also lends itself to well-deserved breaks from the ever more intense action in the war-torn nation. Hachard nicely balances unnerving scenes, such as Kevin barrelling through the woods among “lost shoes and bloody footprints,” with tender online moments, like Kevin and Sara deciding to “pretend it’s New Year’s” and quasi-kiss through a video call.

In one memorable sequence, Sara tries — and fails — to read Mrs. Dalloway, “to prove she could live a life outside of school.” It’s a self-effacing bit of meta-commentary: Virginia Woolf’s challenging experimental novel clearly influenced the adventurous City in Flames. But that enduring modernist work, first published in 1925, is not the only notable predecessor to Hachard’s debut. One may recall any number of Canadian writings occupied with the relationship between language and apocalypse, whether Emily St. John Mandel’s novel Station Eleven, P. K. Page’s short story “Unless the Eye Catch Fire,” or Margaret Atwood’s poem “Spelling,” which includes her oft-cited “a word after a word after a word is power.” City in Flames displays a similar reverence for language. With zeal and vigour, the novel demonstrates the reciprocity that may emerge when modern civilization falls — and words are the material with which humanity must start rebuilding.

Kayla Penteliuk studies and teaches literature at McGill University.