When Clark Kerr, the head of the University of California, Berkeley, was dismissed in 1967, he said, “I left the presidency just as I had entered it — fired with enthusiasm.” Donald Trump made his television reputation by barking, “You’re fired!” (a phrase that Elon Musk has appropriated with gleeful promiscuity). In 1919, the American jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. set the limits on freedom of speech when, in a Supreme Court opinion that is mangled in many retellings, he wrote, “The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.” Near the eternal flame at John F. Kennedy’s grave is a marble slab with an excerpt from his stirring 1961 inaugural address, where he spoke of defending freedom during the chill of the Cold War: “The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it — and the glow from that fire can truly light the world.”

Suffice to say, there are few words in the English language — few metaphors in our rhetoric — more versatile and more powerful than “fire.” Now Edward Struzik confronts us with the white-hot peril of burning in a book both incendiary and intoxicating. With forbidding echoes of the Hungarian journalist Arthur Koestler, it bears the stark title Dark Days at Noon, and it sets out both the past (fires in forests primeval) and the future (more fires raging in more deadly ways in more parts of North America and beyond) in stark and startling ways. The message is clear: the glow from these coming conflagrations will surely set the world aflame.

No one with even a passing acquaintance with contemporary affairs can doubt this. It’s a truth that was rammed home in Canada with the 2016 Fort McMurray fire, which prompted the evacuation of 90,000 people, destroyed 2,400 homes and businesses, scarred 579,767 hectares of land, produced damages that Public Safety Canada estimated at $4.1 billion, and transformed the Athabasca oil sands region into the site of “the most expensive natural disaster in the history of Canada,” as the grim Canadian Disaster Database describes it. The future could be even more dangerous. “It will be more difficult, if not impossible, to live with fire,” Struzik warns, unless humankind halts its impulses to “continue to binge on fossil fuels, degrade the landscape in ways that favour fire, and construct buildings next to mature forests that will inevitably burn on hot windy days when lightning or an arsonist strikes, a campfire is left unattended, or equipment malfunctions.”

The new and dangerous variable is climate change, which raises temperatures, increases winds, produces dry autumns, diminishes snowfalls, reduces the flow of streams and rivers, deepens droughts, and creates a more congenial environment for such insects as the mountain pine beetle, which attacks old trees. “When the trees die, they no longer absorb the moisture that comes with heavy rain or rapid snow melt,” Struzik points out. The result is a perfect storm of catastrophe. Or, to push the metaphor, a firestorm of tragedy.

Only the rare work paid heed to fiery themes.

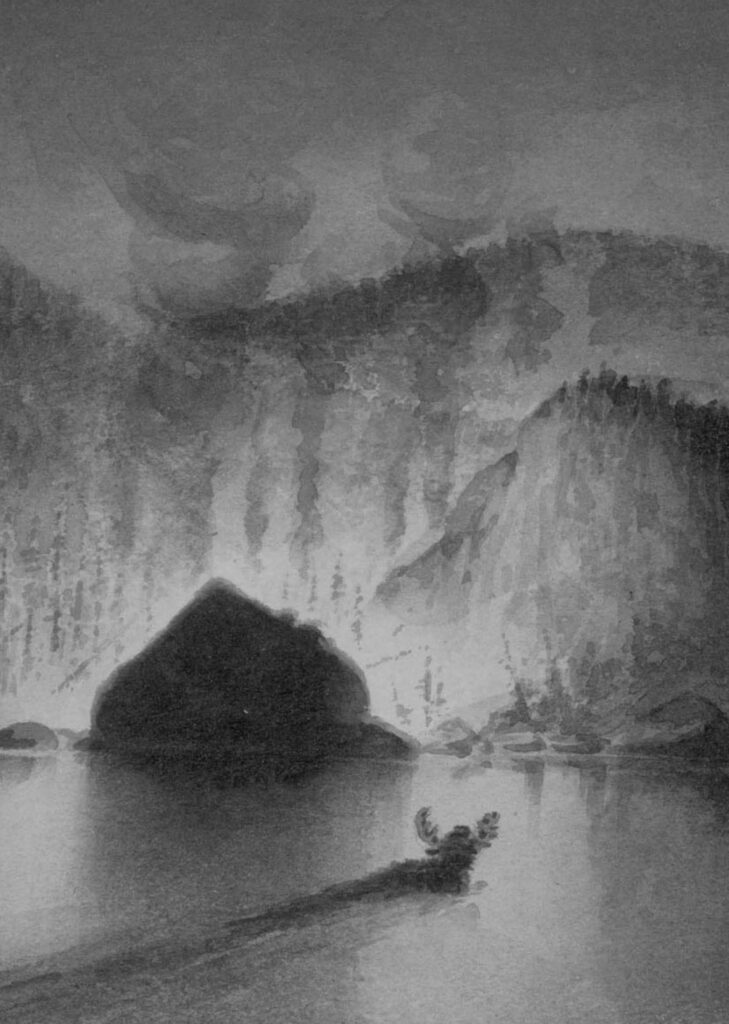

Denis Gale c. 1860; Library and Archives Canada, C-040183k

In truth, this book, with its colourful accounts of fires since extinguished, also has moments that are morally anesthetizing. Think of those paperbacks about shipwrecks that are displayed for sale at Great Lakes ports and seaside resorts or even the Gordon Lightfoot ballad about the Edmund Fitzgerald, lost nearly a half-century ago. Tales of people long dead and perils half forgotten have an ineluctable appeal when brought to life in engaging language and when speaking, as they inevitably do, of the romance of courage amid calamity. The skies of November aren’t the only things that turn gloomy these days, and in his best moments, Struzik, like Shakespeare, demonstrates how, when it comes to fiery episodes, “what’s past is prologue.”

Struzik holds positions at Queen’s University and the University of Waterloo, and he is an incessant writer (and, with reason, worrier) on environmental issues. He also has a peculiar preoccupation with fire; he’s been a first-hand witness at some of the signature blazes of the age, kind of a Canadian version of Arthur Fiedler, the celebrated Boston Pops conductor who was famous for racing to scenes alight throughout eastern Massachusetts. But while Fiedler, who in 1976 sailed to an Ontario Place concert aboard the fire boat William Lyon Mackenzie, was drawn to the drama of the firefighter, Struzik is repelled by the destruction wrought by the infernos that have stained the earth and befouled the air — and that deserve the description, weakened by overuse and misuse, of being “existential threats.”

“The impact of wildfire is no longer just regional, national, or even continental,” he warns. “It has become a global phenomenon with the potential to rival the impact of the Little Ice Age, which was global in scale and freakish in the way it drove hurricanes, intensified drought, and iced up temperate maritime climates such as the one which keeps most of England cool, moist, and free of snow.”

There is nothing modern about forest fires; they long preceded European settlement in what became British North America. But for the early colonists, the large-scale phenomenon of woodlands burning was indeed new. “There was little in the British experience that could teach Canada, or the United States for that matter, much about forest fires,” he writes, “because consequential wildfires did not occur over there with frequency, and those that occurred throughout other parts of the British Empire represented a much different challenge when it came to fire management.”

Nor did fire — one of the classical elements, along with earth, water, and air — attract much if any mention in many conventional histories of Canada, even though some 200 wildfires swept through the prairies alone between 1796 and 1870. And though Struzik credits artists with paying at least some heed to flaming themes, citing Alexander McLachlan’s poem “Fire in the Woods” and Denis Gale’s misty watercolour Moose Attracted by a Forest Fire at Night, he writes:

A wildfire was the one wilderness of horror that most artists didn’t have the desire or the experience to describe. The chaos of colours and the otherworldly tangle of scorched prairie, charred timber, and spongy bogs and fens that often stopped a wildfire in its tracks did not fit into the schemata of the landscape that many learned about and incorporated into their work.

In many ways, then, Struzik’s goal is to fill in the blank pages of history. Mining scores of newspaper and magazine articles and examining more recent accounts of environmental history, he has uncovered what he calls “many extraordinary stories of wildfire that have never been told, details of historic fires that have not yet come to light.” The result is an evocative and provocative look at a powerful force — a welcome contribution at a time of formidable forest fires. Consider that the rapidly expanding fire season can drive violent thunderstorms and spawn fire tornadoes (at least five in British Columbia in 2018). But also consider that these are increasingly unremarkable phenomena — though they were utterly unimaginable only a generation ago.

It turns out that fire is inextricably linked to the folklore that defines the Canadian experience. It will come as no surprise to contemporary readers that the bison was an essential element of the prairie. But Struzik explains how Indigenous communities occasionally used fire to disperse the beasts and thus deny European hunters the meat they needed for sustenance, forcing the unwelcome newcomers to pay the First Nations inflated prices for food. Moreover, the exploitation of the beaver — amply described in Stephen R. Bown’s lively The Company: The Rise and Fall of the Hudson’s Bay Empire, from 2020, as well as Peter C. Newman’s older trilogy on the topic — wiped out hectares of wetlands that might otherwise have tamped down natural forest fires.

Dark Days at Noon explains that fire was the constant companion of both settlers and Indigenous people. In these pages are accounts of, among many others, the 1825 Miramichi Fire in New Brunswick, which poured so much ash and debris into rivers that there was no salmon run for two years; the 1870 blaze in the Ottawa Valley, the smoky fingerprints of which are still evident thirty kilometres away in Burnt Lands Provincial Park; the 1881 Parry Sound fire, which swallowed 518 square kilometres of Ontario forest; the 1910 Baudette–Rainy River fires that left forty-two Minnesotans dead and more than a thousand homeless; and the Porcupine Fire of 1911 near Timmins, Ontario, which burned so intensely that 600 people ventured into a lake to find safety.

The fire might well have been prevented. As the autumn approached, seasonal rangers asked permission to stay on the job so that they could monitor and restrict the amount of burning farmers did after their crops were harvested. Bureaucrats refused their request and told them to go home. Without this oversight, farmers took advantage of the situation. The small fires got out of control on 4 October when a light breeze morphed into hurricane-force winds.

There are many factors to explain the proliferation of fires in the decades that followed the arrival of Europeans in North America, including flawed forest management procedures and, later, the sparks caused by train travel (railways were responsible for 123 fires in 1916 alone). Many of those flames were simply blamed on First Nations, however. Robert H. Campbell, who directed the Dominion Forestry Branch in the early twentieth century, believed, without evidence, that “Indians generally have the reputation of being careful with fire but the occurrence of many fires at a distance from the regular routes of travel and on trails followed only by the Indians would indicate that they have not yet learned to take the necessary precautions.”

Of course, Indigenous people were quite often the victims of fire. In 1919, for example, a blaze ripped through Lac La Biche, in northeast Alberta near the border of Saskatchewan. “We were all badly burned, especially my father,” a Cree woman named Theresa Desjarlais later recalled. “The horsehide which he had thrown over my mother and little sister had burned to a crisp on Mother’s back.” A train was most likely responsible. But, Struzik says of the shameful cultural clash, “it was easier, of course, to do something about ‘Indian burners,’ as they were called, than it was to strongarm powerful railroad companies like the CPR, which was given $25 million, ten million hectares of free land, and a twenty-year land tax deferral in 1880 to build a railroad across the country, including across land that legitimately belonged to Indigenous people.”

In later years, Canada would experience the landmark 1950 “weird red smog” that covered southern Ontario; a spate of fires in Manitoba in 1989; and the 2011 fire in Slave Lake, Alberta, which sent all 700 residents fleeing. Throughout the Arctic, meanwhile, peat-burning tundra fires have increased “in scale and intensity.”

Novel means of fighting flames emerged over time — from observation towers and surplus First World War airplanes to the use of trenches that impede the movement of fires and various ways to ignite backfires. And prevention took a giant step forward with the creation of a fire-danger rating system by two Canadians, James Wright and Herbert Beall. But Struzik remains critical of this country’s fire bureaucracy and its policies, as well as how governments worldwide have been overwhelmed by the challenge of climate change:

The situation in Canada typifies the challenges that many countries face if fire continues to burn more often and intensely. Two thirds of the country depends on water that is stored and filtered in forests. In many places, the quality of that water is already being degraded by drought, pollution, climate change, agriculture, and urban development. Groundwater may be keeping cool and clean in places such as Lost Creek and possibly in Waterton National Park, but no one in Canada knows for how long because few jurisdictions and agencies have adequately mapped out, evaluated, and diligently protected underground aquifers.

And so: prepare yourself for more dark days at noon, and throughout the morning and afternoon hours too. The future of fire — the foreboding and forbidding outlook Struzik reflects in his subtitle — is bright because our leaders, aware of the threat yet unable to address it, are dim. The blazes of tomorrow will have the (smoky) air of the Biblical revelation of a “great mountain burning.” Alas, the phrase “scorched earth policy” will cease to be a metaphor.

David Marks Shribman teaches in the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University.

Related Letters and Responses

@kujjua via Twitter