Readers may not open Swamplands expecting to learn much about art history, yet that is one of the many lessons Edward Struzik offers in his timely and enchanting disquisition on the many facets of peat. Before the Group of Seven set their brushes to capturing the boggy beauty of Georgian Bay in the 1920s, Struzik explains, Canadian landscapes looked suspiciously like the rolling hills and dales of the English countryside. Maple and oak dominated these paintings, rather than the brooding, windswept pines that greeted the likes of A. Y. Jackson, Lawren Harris, and Arthur Lismer, as well as Tom Thomson before them. The wilder parts of Ontario were an environment that at least one critic back in Toronto considered “a repulsive, forbidding thing.” Eventually, of course, the art world came to celebrate the “awful splendor” of the bay and the “slim, peat-filled frost fractures in the Canadian Shield.”

Struzik covers a lot of ground as he fills us in on the cultural and ecological significance of that sometimes misunderstood turf. Over centuries and millennia, this partially decomposed plant material accumulates in thick layers in waterlogged, anaerobic conditions that hinder microbial activity: “Typically, plants that die, leaves that are shed, and insects and animals that perish are broken down by bacteria, insects, and chemicals in the ground. Anyone who composts knows how this works. This process does not happen as quickly in cold, wet regions and on soil that is frozen and covered in snow for most of the year.”

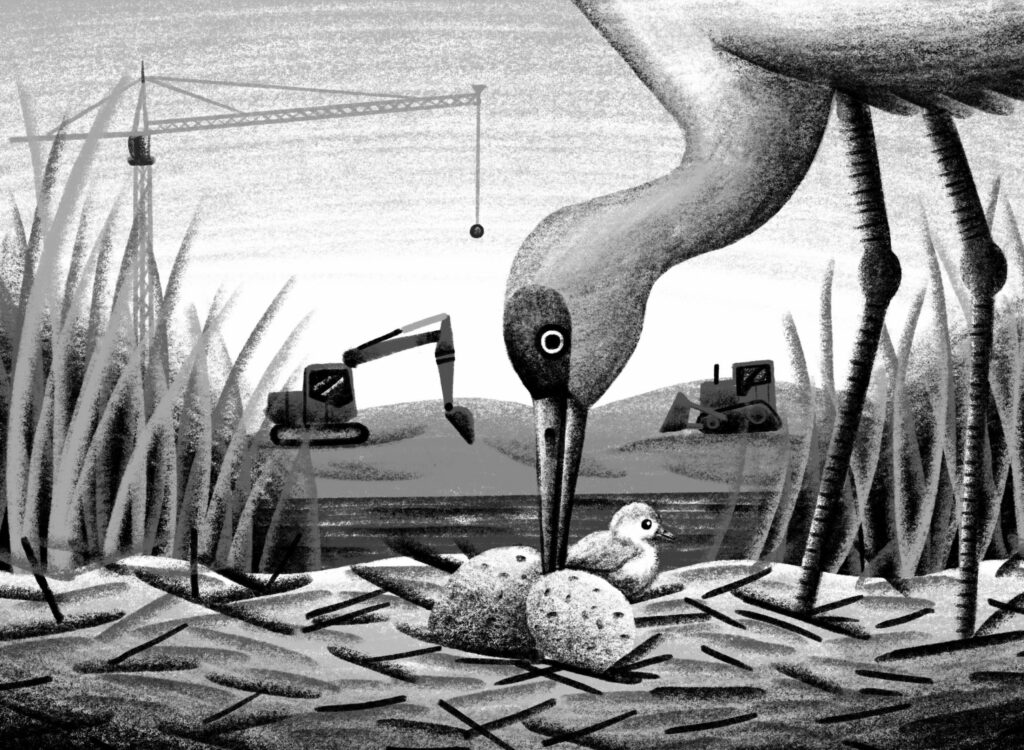

Competing views of critical habitats.

Alexander MacAskill

Many such ecosystems formed toward the end of the Last Glacial Period, when ice sheets extending thousands of kilometres began to melt and flood the surrounding areas. When the vascular plants died, moisture-loving species — like sphagnum moss in the boreal peatlands, sawgrass in the Everglades, even palm in the vast wetlands of Indonesia — took over, eventually leaving behind layer upon layer of carbon-dense material.

Historically, many people didn’t care much about this spongy substance, except when it could be dug out of the earth and burned for fuel. It was believed to be far better to drain a quagmire to make way for forests, roads, crops, and cottages. Yet a healthy peatland can stop a raging wildfire in its tracks or absorb excess moisture during heavy rains and coastal surges. Depending on the specific climate, wetlands are home to rare orchids, denning polar bears, sleeping rattlers, whooping cranes, and many varieties of endangered plants. And though fens, marshes, bogs, and the rest cover only about 4 percent of the earth’s terrestrial surface, they sequester a whopping 0.37 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide a year —“more carbon than all other vegetation types in the world combined.” In other words, planting trees is a great way to combat greenhouse gas emissions, but “dollar for dollar, a climate-mitigation investor would get bigger returns by growing or accumulating peat.”

A fellow at the Queen’s Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy, in Kingston, Ontario, Struzik examines the cultural, economic, and natural forces that are threatening critical habitats around the world and what we can do to save them. With lively prose and many irreverent asides, he transports readers from the “swamp forest” in Peninsular Malaysia to the fens of California’s Mojave Desert, which used to be covered in “peaty wetlands.” We also visit the misshapen pingos, or ice-cored hills, of Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, where the remains of the old town are sliding into the sea as the melting shoreline turns to mush. “There is exquisite beauty in the tundra if you take the time to look,” Struzik writes of this place. “The thawing and freezing of peat and minerals in the permafrost can result in artful, polygonal patterns that are widespread in terrains such as this.”

Struzik may not be the most evocative of nature writers — he often eschews vivid description for long lists of species names — but he excels when he turns his attention to people, whether hydrologists, bryologists, conservationists, or the daughters of a Gaspésie peat-mining dynasty. The tough “characters” he mentions are obsessive and funny, as resilient as the moors and marshes to which they devote their lives. These are people who show how a spirit of care for the natural world might just sustain us a while longer. Readers will not soon forget Fran Gilmar, for example, who at seventy-seven is fighting to save a pristine mountain fen in Alberta from an Australian coal-mining company. The former figure skater “talked as if she were in a pulpit,” Struzik writes, “driving the devil from her congregation of moose, elk, wolves, bears, cougars, trout, and the rare plants she covets.” In the western Arctic, a group of permafrost scientists entertain themselves with a game of “page watch,” competing to see how many blackflies they can each kill by opening and closing a thick book. Struzik suggests they have one of the ten worst jobs in science — ranking right above the orangutan-pee collector and just below the human-semen washer — but they nonetheless are dedicated to their work in the “intense cold” and “stifling heat.”

When he’s not describing the people or the landscape, Struzik writes at length about nation building, identity and myth, and law. Instead of dwelling on the precise chemistry that makes some bogs acidic and others alkaline, he unearths the tangled roots of how we regard — or disregard — these complex ecosystems. For some, peatlands are “a cultural resource, a backdrop to poems, stories, and songs, the source of the sweet scent of peaty smoke-infused Scotch whisky, a record of the past, a reminder of the horrors of slavery and concentration camps, and the inspiration for mythical stories that remind us that wilderness can be warm and embracing just as much as it can be sublime, dangerous, and spooky.” In Ireland, for instance, peat has been a cornerstone of the economy and a “confirmation” of national identity. The Netherlands owed its imperial excursions to the wealth generated by draining its extensive wetlands for agriculture and by using peat to power industrial activity. And throughout North America, many settlers took their cues from an eighteenth-century English ethos of land management, which held that it was “a farmer’s Christian duty” to dry out every last bog and mire.

Struzik pokes and prods at the twinned logic of colonial expansion in the United States: the taming of the land and the taming of the people. “I did not see what connected Pocahontas and her people, enslaved persons, the Underground Railroad, and the Civil War,” he writes, “until I drove from Jamestown to the Great Dismal Swamp, a vast peatland that stretches out along the border of Virginia and North Carolina.” Early colonists attempted to drain and slash their way through this region, initially to grow tobacco, rice, and hemp. Then the Dismal Swamp Company, in which George Washington invested, began transforming the terrain on a much larger scale, through forced labour. Escaped slaves would later seek refuge in those same swampy interiors, braving the panthers and wolves for a life away from the greater horrors of the plantation.

Another player was Henry Flagg French, an agriculturalist and lawyer from New England, who was appointed assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury in 1876. French had “a kind of Manifest Destiny for getting rid of bogs, fens, and marshes” and saw no reason to “spare even the remotest wetlands that dominated much of the American landscape.” One of his innovative solutions, which we still use today, was weeping tile, or the French drain.

In Canada, peat bogs constitute some 12 percent of the nation’s landmass, and much of our history has emerged from their murky depths. Stretching at least 300,000 square kilometres from Quebec through Ontario and into Manitoba, the Hudson Bay Lowlands make up the world’s second-largest peatland ecosystem and are home to the seven First Nations of the Mushkegowuk Council. (The word “muskeg” comes from Cree and Ojibwe words that mean “grassy bog.”) That did not stop Ottawa from offering up some of the “valueless” territory to the British military for early nuclear testing, just as it has not stopped mining companies from staking claims to the mineral-rich wetlands of the so‑called Ring of Fire. (The first proposal, at least, did not come to fruition; the Brits chose instead to detonate their bombs in Australia, fearing that northern Canada would be too cold for their personnel.)

Of course, not everyone in North America has been blind to the value and beauty of the morass. Struzik is conscientious in recognizing communities like the Powhatan Confederacy, who “made do with what peatlands like the Great Dismal Swamp offered,” and the Mackenzie Inuit, who lived “prosperously” on the caribou, berries, and root vegetables they gathered at Kitigaaryuit. Still, Swamplands prioritizes scientists and policy experts, whose perspectives can overpower contemporary Indigenous voices. Long-term solutions to wetland degradation will surely require listening to both.

At times, Swamplands lacks focus. Consider how the chapter titled “Central Park” ends inexplicably in the Everglades or the way an inquiry into moths becomes as much about the secret lives of entomologists. But ultimately this is a book that stands apart for its playfulness and curiosity, for a sense of wonder that does not yield to despair or grief. And that’s saying something, considering all the recent media reports warning that many of the earth’s permafrost peatlands are on the verge of releasing billions of tonnes of carbon, along with substantial amounts of mercury.

Near the end, Struzik introduces us to Line Rochefort, a scientist in Quebec, where the peat-mining industry stretches back generations. Rochefort and her team have managed to grow new peat by using a foundation of sphagnum and brown moss to restore bogs and fens. The resulting ecosystems, while not as prolific as those in the wild, still support many of the species you might expect to find. “The story of peatlands is sobering,” Struzik admits. “But the future of peatlands does not need to be as melancholy and hopeless as the melting of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice.” For the reader who is anxious about climate change, this is one source of good news.

Gayatri Kumar lives and reads in Toronto.

Related Letters and Responses

@egies via Twitter