When I was growing up in Montreal, way back in the early 1960s, the annual visit of the Shrine Circus was a very big deal. Beginning in 1939, the Karnak Temple chapter brought the circus to the old Forum every May as a fundraiser for the Shriners’ Hospital for Crippled Children (as it was then called). Aerialists and acrobats! Clowns! Shriners dressed like “sheiks” and driving tiny little cars! A lady shot from a cannon! But, most of all, lions and tigers and chimpanzees and bears and elephants. I still remember the thrill of proximity as the elephants made their stately way into the ring and the gasps of appreciation as they stood on little stools or rolled on barrels or “danced” in grass skirts or rose on their hind legs to balance against one another. For a child back then, seeing these animals and being close to them, whether at the zoo or at the circus, was a way of loving them. We weren’t aware of the grievous insult to their dignity. And we didn’t know that we were loving them to death.

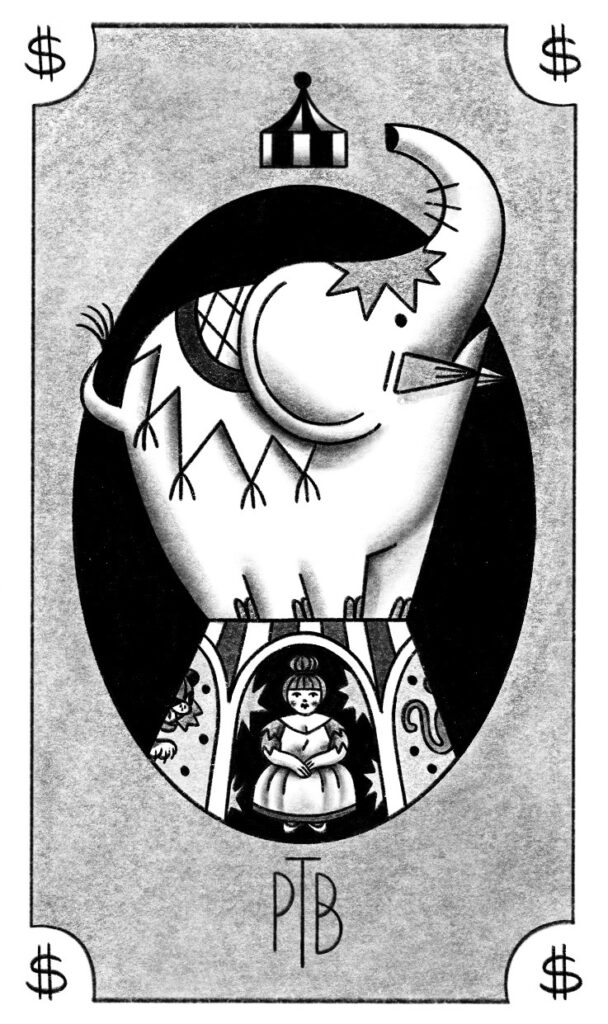

The circus is the setting for Jumbo, Stephens Gerard Malone’s latest novel. Jumbo was, of course, the enormous African elephant whose name became synonymous with great size. Born in Sudan, where he was captured as a calf after his mother was killed by a poacher, Jumbo was housed at the zoo of the Jardin des Plantes, in Paris, before being acquired by the Royal Zoological Gardens in London. Matthew Scott, a self-taught keeper and breeder, was sent to accompany the young bull to his new home. Scott found Jumbo in a heartbreaking physical condition, diseased and almost blind. He nursed the animal he called his “friend and companion” back to health, and Jumbo spent the next seventeen years in London, giving children, including those of Queen Victoria, rides in the howdah on his back. In 1882, he was sold to Phineas Taylor Barnum, the American showman and circus owner, for a whopping $10,000.

Both Scott and Barnum feature in Jumbo, though its main character, Little Eyes Nell Kelly — the “tiniest, most perfectly formed woman in the world”— is fictional. Born in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, Nell is, in 1873, at the age of ten, sold by her mother to Barnum for $25 a week. When Nell asks if she can return home, Barnum and his men laugh. “My child! You are blessed!” the impresario tells her. “Everyone wants to be in my menagerie!”

Nell is soon Barnum’s premier attraction, her face adorning the giant canvas signs hung on the side of the circus’s train. She is even taken to London to meet the Queen: “Barnum spent a hundred pounds more to dress her in billowing velvet with crimson and gold trim. A genuine diamond tiara was tucked into her wig.” But her star status, which comes with perks such as a private railcar, is diminished by the arrival of Jumbo, accompanied by his London keeper, Matthew Scott. The world’s tiniest woman is displaced by the world’s biggest elephant.

About that elephant in the room.

Gwendoline Le Cunff

Despite her strong identification with caged animals, Nell vows to hate Jumbo: “Him being here taking away everything she had!” But, rather predictably, she finds she cannot hate him. When Barnum’s chief animal trainer, Elephant Bill, determines to break Jumbo through brutal use of a bull hook, Nell recognizes the animal’s reaction: “She’d seen something like that before. In a mirror.”

Indeed, Elephant Bill, who took pleasure in “beating the horses while staring at her like he’d not eaten in days,” has been raping Nell. When she appeals to Barnum, she’s accused of lying. “I’m nothing more than an animal,” she thinks. “No better than Jumbo.” Soon enough, Nell is bunking with Jumbo and Matthew in a railcar sodden with elephant piss. And, soon enough, she falls in unrequited love with Matthew, who has eyes only for the elephant.

The real-life Matthew Scott published a biography of Jumbo in 1885, the year the elephant would die. “He was given to me a baby,” Scott wrote, “and I have been more than a father to him, for I have performed the duties and bestowed the affections of a mother as far as my humble ability would permit.” The horrifying conditions that his beloved friend — his “son”— endured as the greatest attraction of the Greatest Show on Earth broke Scott’s heart and his spirit. But, against all evidence, he clung to the fantasy that Jumbo would one day be released from the circus and could somehow return to Sudan.

Malone depicts the suffering of circus animals like Jumbo in passages that are difficult to read: Their capture. Their transportation to Europe or North America, crammed into the dark holds of ships, often unwatered and unfed, with an unconscionable number dying in the passage. A life of bondage and performance for those that survive. Jumbo’s trials, in particular, are rendered acutely. He is chained for long hours in a “cramped and fetid railcar” as the circus travels from town to town for months on end. Listless and depressed, he becomes weak and emaciated. These descriptions, terrible as they are, constitute the novel’s strength.

Jumbo’s famous death — he was struck by a Northern Trunk freight train in St. Thomas, Ontario — occurs two‑thirds of the way through the book. The remainder takes Nell once again to London, where Jumbo’s stuffed hide and skeleton are displayed and where she blackmails Barnum for the sum of $100,000. His terrible secret? Barnum had arranged for Jumbo, by now worth more dead than alive, to be killed. With the money in hand, Nell looks after Matthew, who has become a severe alcoholic, paying for six months of his keep at a rooming house in Maine. And she takes a pilgrimage to Sudan, guided by the wild animal merchant Carl Hagenbeck, another real‑life character. Disguised as a young boy, Nell travels by ship, by camel caravan, and on horseback, finally arriving at the River Royan. There she tosses a small satin box, containing a bit of Jumbo’s ivory, into the river: “He’s home now, Scotty.”

That’s an awful lot of drama packed into 226 pages of narrative. And I haven’t even gone into a romantic subplot involving another unrequited love. The novel might better have maintained a closer focus on the milieu of the circus, giving the reader room to draw the comparisons that were clear to many even at the time. In recounting Jumbo’s removal from London and from his elephant “wife” Alice, for example, Matthew Scott wrote, “We took steps to tear those poor slaves apart.” The analogy is apt.

Jo-Ann Wallace was a professor emeritus at the University of Alberta. Her memoir collection, A Life in Pieces, is due out fall 2024.