On November 16, 1976, I had a rendezvous with Gérald Godin, who, to general astonishment, had just defeated the Liberal premier Robert Bourassa in his own riding, helping to sweep the Parti Québécois to power. We had never met, but I had known about Godin for several years. Malcolm Reid had written about him in his 1972 book, The Shouting Signpainters, and we had several mutual acquaintances, as he had friends in English Canada’s progressive circles.

It had snowed overnight, and as I trudged along toward the restaurant in his east-end Montreal constituency, I was convinced he would not show up. The celebrations the night before had gone on for hours, and I was sure that keeping an appointment for a coffee with an Anglo journalist would not be a priority. But he was there. At one point during our conversation, I confessed that, as an English Canadian, I was nervous about the election of the PQ. He reached across the table, touched my hand, and said, “Don’t worry.”

What I did not know until I read Jonathan Livernois’s Godin was that the thirty-eight-year-old had been at the restaurant for two hours. His first meeting there had been with a local priest, who told him that a parishioner had died of a heart attack after being turned away at the hospital because its director general said that the quota of patients had been reached. “Let us go together to see this director general,” Godin told the priest. That response was typical of a commitment to his constituents that lasted his entire political life.

Born in November 1938, Gérald Godin was a poet, a journalist, a radio producer, an actor, a publisher, a professor, a left-wing activist, and the singer Pauline Julien’s partner. In 1961, he came to Montreal from Trois-Rivières, where he had been working for the local newspaper, to take a job with Le nouveau journal. Its collapse in 1962 led him to retreat to his hometown before coming back to Montreal a couple of years later.

A professor of literary and intellectual history at Université Laval, Godin’s biographer has also written about Maurice Duplessis, another politician originally from Trois-Rivières. Given his previous research, Livernois makes some connections between the two men that seem improbable. In his earlier book, Livernois identifies himself as “born in 1982, an essayist, situated on the left, a perplexed indépendantiste, who has no particular animosity” toward Duplessis. This lack of animosity leads him to describe Godin as having adopted a “duplessisme de gauche,” a kind of left wing populism.

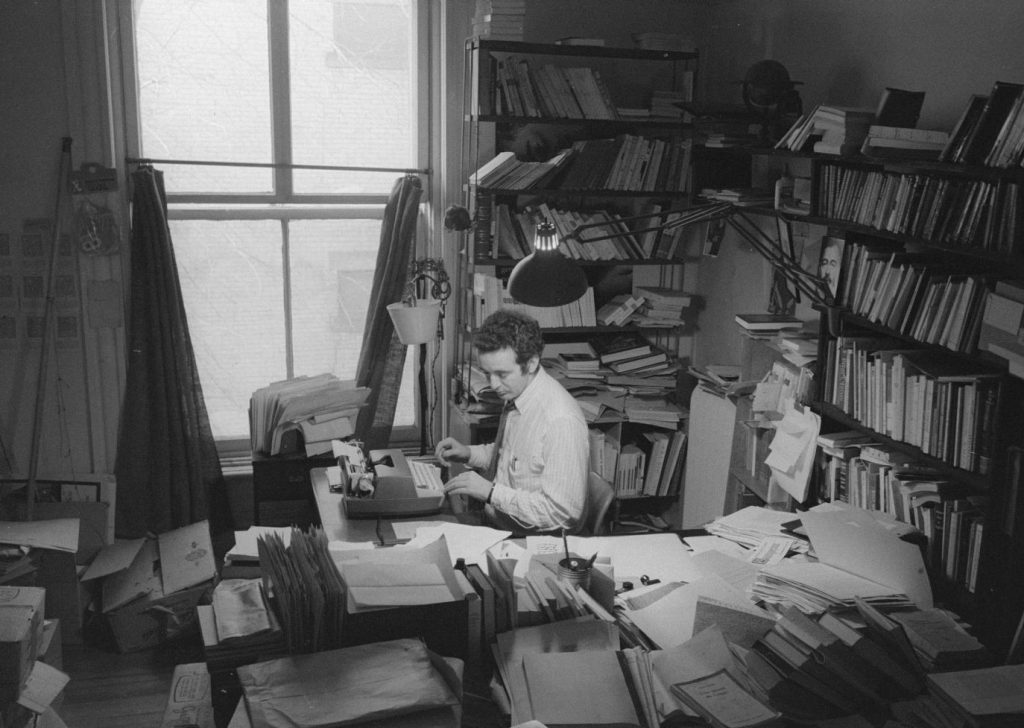

A young writer and future politician at work in his home office in Montreal.

Gabor Szilasi, 1969; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec

The comparison to Duplessis seems to me to be a stretch. There was nothing authoritarian or ruthless about Godin; his politics were shaped by compassion. His years in Montreal, before his election in 1976, were spent working for Radio-Canada as a researcher, writing for struggling left-wing publications like Parti pris and Québec-Presse, and publishing books of poetry. Godin led a bohemian life. His house on Carré St Louis was open to friends at all hours of the night. He was unfailingly generous, once giving away his only television set to a needy constituent. And his passionate relationship with Julien did not prevent him from having a series of affairs, which infuriated her. (She also wasn’t happy that he gave away their TV.)

The son of a doctor, Godin disliked the social prejudice against working-class French people, and he often told a story of sitting on a park bench, reading a book as two labourers chatted nearby. He concluded that his holding a book had made them uncomfortable, because he heard one of them say to the other, “On parle mal, hein?” (We speak badly, don’t we?) As Livernois points out, Godin told Reid that a friend had originally shared the anecdote with him, but he told an interviewer twenty years later that he had experienced it himself. Either way, it was a moment that helped drive him to use the language of the working class — joual — in his poetry.

During the October Crisis of 1970, Godin was arrested and jailed — along with Julien and the other people who were staying at their house. It was an experience he never forgot or forgave. When Pierre Trudeau stepped down as prime minister in 1979 — temporarily, as it turned out — Godin was one of the few members of the Assemblée nationale to vote against a motion of congratulations.

In 1976, Godin decided to seek the Parti Québécois nomination in the Montreal riding of Mercier to run against Bourassa. The party’s leader, René Lévesque, did not want Godin as a candidate and tried, without success, to persuade other people to contest the nomination. After he won his seat and Lévesque became premier, Godin remained a backbencher throughout the government’s first mandate.

During those four years, Godin became a kind of informal ambassador to English Canada, travelling to Halifax, St. John’s, Moncton, Hamilton, London, Toronto (ten times), Regina, Edmonton, Calgary, Winnipeg, St. Boniface, Saskatoon, Vancouver, and Victoria. Closer to home, he reached out to immigrant communities with warmth and empathy.

Gradually Godin won over Lévesque and was named to the cabinet, first as the minister of immigration in November 1980 and then, after the 1981 election, as the minister of cultural communities and immigration. In September 1982, he was given responsibility for the Charte de la langue française — the language legislation that’s still known as Bill 101. When he named Godin, Lévesque quipped, “I am looking forward to seeing how a guy caught between a rock and a hard place will get out of the jam.”

As Godin told me at the time, “I was caught between, on the one hand, people in the nationalist movement who said, ‘Any change in Bill 101 is unacceptable,’ and, on the other hand, people who said, ‘Godin is the new Goebbels.’ ”

In his opening statement before a committee of the Assemblée nationale, Godin explained that while French was threatened by technology, for which English was the universal language, he was not blaming the English community. “Let us be clear,” he said. “Anglo Quebecers have very little to do with this assimilation, and it is not they we should consider responsible, or their institutions.”

I have dwelt on this topic more than Livernois does, in part because I think he underplays the significance of Godin’s relationships with English-speaking Quebec and English-speaking Canada, and in part because the current Quebec government refuses to make the distinction that Godin understood.

Godin’s career was suspended not long afterwards, when he suffered a devastating brain tumour. He recovered following an operation but would admit that he had considered suicide.

The following year and a half was chaotic for the Parti Québécois. After Lévesque talked about taking “le beau risque”— giving federalism another chance under the new prime minister, Brian Mulroney, rather than committing to a second referendum on sovereignty in the next mandate — a third of his cabinet resigned in protest. Throughout the turmoil, Godin remained loyal to the premier.

Following the resignation of Lévesque in the spring of 1985 and the succession of Pierre Marc Johnson, the Parti Québécois was defeated and Robert Bourassa returned to power. Two years later, in the fall of 1987, Godin gave an interview saying that Johnson had to go. It was a fatal blow to the PQ leader. A year after that, Godin was re-elected with his largest majority ever. He had become a saint. “People came to touch him,” one of his friends said. “They think they are going to have indulgences, that they will be cured!” Godin said with a laugh.

Whether he was a saint or a sinner, his cancer returned, and he was increasingly weak and confused. Colleagues like Louise Harel were assigned to help him. His last speech in the Assemblée nationale, on June 8, 1993, was on Bourassa’s own language legislation. “The man has slowed down, has difficulty finding his words, confuses certain things,” Livernois writes, in reference to that day. “You can hear Louise Harel, beside him, whisper a few words to him from time to time. The speech is marked by a great culture but is completely disorganized.” Godin died sixteen months later, in October 1994.

Gérald Godin is remembered now for his openness to immigrants, which stands in dramatic contrast to the views of the present Quebec government. His poem “Tango de Montréal,” a lyrical tribute to the immigrants in Montreal, is engraved on a wall near a metro station in a square named after him. What is often forgotten is how he built bridges with progressives in the rest of Canada. He was a man of great generosity of spirit.

Graham Fraser is the author of Sorry, I Don’t Speak French and other books.