There was a time when Winnipeg was the railway hub of Canada, a Chicago North. Trains led commerce east and west and stopped here on the prairie to retool and load up. That’s over. Commerce flies overhead now, and Winnipeg watches the contrails.

It’s less known that Winnipeg, in the early twentieth century, was also a hub of psychic activity. Some think that activity persists to this day. By “activity,” I mean the buzz and garble of the dead. Local filmmakers and artists like Guy Maddin and the late Sigrid Dahle have plugged into an unconscious that can be both creepy and playful, always Freudian: dead fathers, dead sons, something important gone missing. It’s significant that there are more funeral homes in Winnipeg than Starbucks outlets; gothic cemeteries like Elmwood and Brookside are full of our unique prairie history. Especially on Halloween, the city carries a reputation of being haunted. It might just be an economic metaphor: business abandons the place, the dead and dying are left behind, restless. “My city’s still breathing, but barely, it’s true,” sing the Weakerthans, “through buildings gone missing like teeth.” There are other, more literal signs of a special connection to the afterworld: in 1998, for example, there was trouble at Elmwood Cemetery. The high ground eroded and threatened to release long-interred caskets into the Red River: 108 graves had to be moved. This was discussed in town not so much as an infrastructure problem but as folklore: it was “the year they wouldn’t stay buried.”

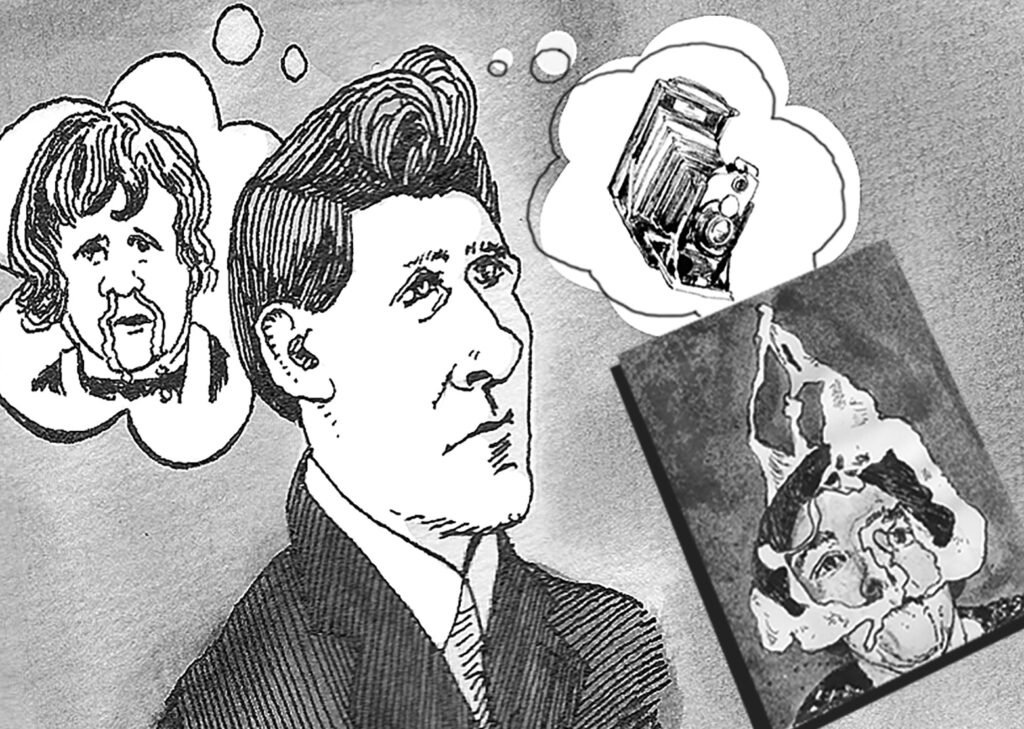

It’s not a bad thing. Winnipeg is authentic. Here, what’s repressed is allowed to return, unlike in high-strung cities like Vancouver and Toronto, which live out all the Freudian symptoms of urban anxiety: depression, self-destructive behaviour, binge spending, compulsions. Winnipeg is more at peace with its ghosts, not trying to outrun them. Case in point: Thomas Glendenning Hamilton, a surgeon, school trustee, Liberal member of the Manitoba legislature, member in good standing of the United Church of Canada, and a holder of seances at Hamilton House, the family home at 185 Kelvin Street (later renamed Henderson Highway), not far from the cemetery where, decades later, some corpses were at risk of being swept away. The man himself died in 1935, but his house is still there. It’s now home to a shop called Gags Unlimited.

The respected surgeon devised ways to commune with the dead using the latest technologies.

Silas Kaufman

T. G. Hamilton married Lillian Forrester, a nurse from Emerson, Manitoba, and they had four children. In 1919, one of their sons died of the great influenza, and it was after this loss that Hamilton and his wife embarked on a study of — perhaps a personal obsession with — contacting the dead. Consider the time: The pandemic had ravaged the West, thousands had died, and all this grief had come on the heels of the meat grinder of the First World War. Many Winnipeg families had lost sons, daughters, parents. And the idea of communicating with the dead seemed reasonable: it was the early age of radio. If voices could be tuned in from thin air with a gas valve and cat whiskers, why not the voices of the dead? Hamilton’s Scottish nanny, Elizabeth Poole, turned out to be a skilled medium. Her specialty was table tipping, in which participants with their hands on a table called out letters of the alphabet. When the table tipped, the next letter was called, until a sentence was revealed, as in a Ouija board session. It was a matter of having a sensitive receiver (Poole) and the right apparatus (kitchen table).

The seances started out small, local. But word got around. Isaac Pitblado, the president of the Law Society of Manitoba and one of the so‑called Committee of 1,000 that violently put down the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919, became a regular at Kelvin Street. In later years, the Hamiltons hosted William Lyon Mackenzie King and Arthur Conan Doyle, who said Winnipeg should be “a psychic centre.” His letter is reprinted in an elaborate and startling new book of essays, pictures, and art inspired by the Hamiltons’ collection of seance photographs and by contemporary art, The Art of Ectoplasm: Encounters with Winnipeg’s Ghost Photographs.

Hamilton and his wife took over 700 black and white photographs of the seances they hosted between 1923 and 1944, or at least that’s roughly how many found their way into the University of Manitoba Archives. The idea was that the camera, a simple technology in the days before Photoshop and artificial intelligence, would tell the truth.

At any given seance, a group would gather around Elizabeth Poole and first calm the room’s energy — by singing songs like “Unto the Hills” and “Lead, Kindly Light.” Hamilton rigged a series of up to eleven cameras, some stereoscopic, some with flash, in the otherwise dark room, to catch the action. A box, in which a bell connected to a dry‑cell battery would, somehow, ring when spirits were nearby, alerted Hamilton to trigger the shutters. The results are remarkable: starkly lit images of Poole in a trance, with “ectoplasm” running from her nose and mouth. To modern eyes, the substance looks very much like cheesecloth, but it was meant to show evidence of ghosts. Conan Doyle would later write that ectoplasm, as he experienced it first-hand, would behave like the eyes of a snail: retracting when touched and re-emerging when free to do so. If one pinched the ectoplasm, it would cry out in pain. Some of the ectoplasm in the Hamilton photographs appears to contain human faces. (Upon closer inspection, it’s actually other photographs cut up and pasted on top of the cheesecloth.) There’s even a shot of Conan Doyle himself, after he died, emerging from Poole’s mouth. His widow, Jean Leckie, had travelled to Winnipeg to make contact with him.

To a reader flipping through the pictures today, it’s obvious that many have been tampered with. But at the same time, one feels as if something authentic and otherworldly was captured back then. There’s no overacting or vaudeville splash. The scenes are clinical, unfussy, except for the globs of ectoplasm or gauze or whatever it is. The scenes are also ugly, but as Hamilton’s daughter, Margaret, points out, in one of the gathered essays, birth is likewise ugly, as is open-heart surgery. Miracles all.

Which brings us to the strange afterlife of the Hamilton Family Fonds at the University of Manitoba and the way in which the photos have inspired essays and art over the years. Seemingly, no one who studies the work is ill-mannered enough to claim that Hamilton was a charlatan, that he faked it. According to Serena Keshavjee, the editor of The Art of Ectoplasm, those who have worked with the pictures “tend to be more interested in uncovering lost histories to better understand cultural trends than in judging alternative science and marginal religious movements.” The impulse, for fans and academics, is not to patronize or debunk but to look and imagine what exactly was going on at Kelvin Street.

It matters that Hamilton found spirituality after his son died of the flu. It matters that science and culture in the early twentieth century seemed to agree on keeping an open mind. It was all supported by empiricism, or so Hamilton believed: the photographs wouldn’t lie. He built contraptions to measure the tipping of tables, kept detailed logs, even took wax moulds of fingertips of dead visitors, including, in 1924, those of Robert Louis Stevenson, who wrote Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and had died thirty years prior. (Interested readers can see the author’s fingertips on page 139.)

It matters, too, that Hamilton never became famous for his collection outside the gossips of Winnipeg and the parlour eccentrics like Conan Doyle and Mackenzie King, and that he didn’t grow rich from his sideline. He gave over a hundred lectures in Canada, the United States, and England with the primary result being that his medical practice (and income) suffered. It matters most of all that what Hamilton traded in, at the end, was hope: he loved his son. Most of us, even if the pictures look doctored, can still relate to the motivation. As the science fiction author Jeff VanderMeer recently wrote in The Paris Review, “Our hauntings in the modern era so often now are not ghosts but simply the things we cannot see — but that radically affect us.” Just think of the coronavirus and climate change and creeping fascism and, of course, grief. Hamilton’s quaint but striking pictures bring to mind something near to hand but still unreachable. His story is a love story.

Tom Jokinen lives and writes in Winnipeg.