In January 2021, ten Nepali climbers solved what mountaineers liked to call “the last great problem”: a winter ascent of the notorious K2. On this expedition, in contrast to many others, no Western “clients” accompanied the Sherpas, some of whom celebrated by dropping their oxygen masks and singing their national anthem on the summit, the world’s second highest. Millions of viewers on social media were captivated by their obvious pride and joy atop a peak where temperatures can reach minus 60 Celsius.

The story of that K2 climb is detailed, along with many others, in Bernadette McDonald’s riveting book Alpine Rising: Sherpas, Baltis, and the Triumph of Local Climbers in the Greater Ranges. The author from Banff, Alberta, interprets the Nepali ascent as marking a cultural shift in addition to a significant mountaineering achievement. Among those ten men were superstars of the sport: national heroes with large online followings. Many were second- or even third-generation Sherpas who help attract hundreds of millions of dollars in tourism revenues each year. One of them, “smooth-skinned, baby-faced” Nirmal Purja, would soon star in a Netflix documentary, 14 Peaks: Nothing Is Impossible.

“Did Western observers finally grow to accept and recognize, applaud and reward the accomplishments of climbers from Pakistan and Nepal?” McDonald wonders in light of the group’s success. “Was there an increasing awareness of the need to move beyond a colonialist view of mountaineering to one that was more inclusive, more equitable, and more just?”

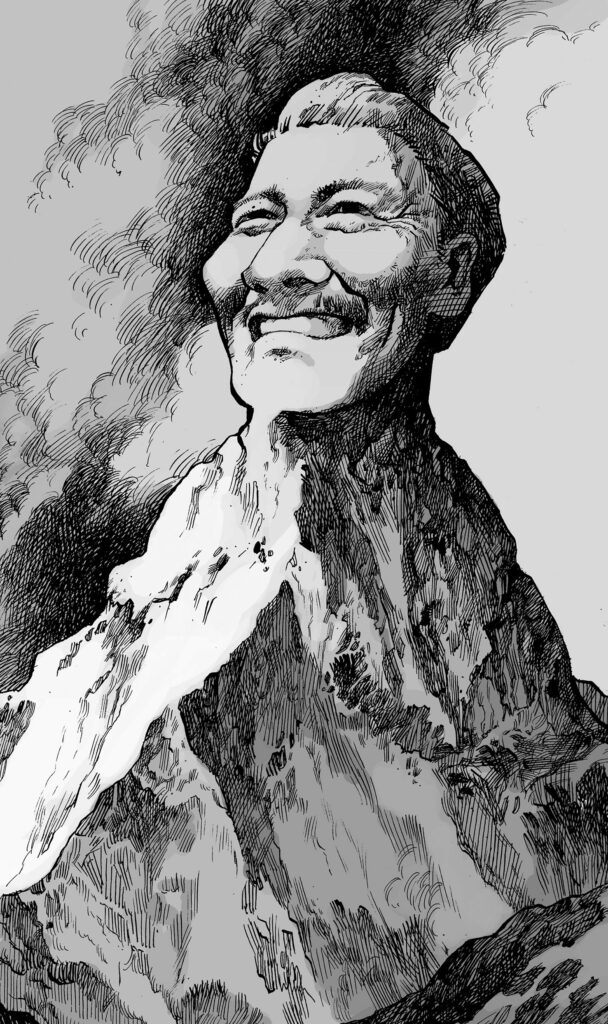

Tenzing Norgay and other peak performers.

David Parkins

McDonald goes on to answer these and other questions with a compulsively readable history of sky-high ventures — including some that have long been kept secret — that stretch back to the original British expeditions to Mount Everest following the First World War. Since then, Nepali and Balti men and women have been at the forefront of Eurocentric nationalist pursuits of climbing glory. While the Baltis are not as famous as the Sherpas, a Nepali ethnic group, their assistance has been vital in scaling the unforgiving remote peaks in the Karakoram Range of eastern Pakistan, home to countless soaring mountaintops, including five of the world’s highest.

Historically, there’s no evidence that yak herders or subsistence farmers in the Greater Ranges of Asia ever set foot on a mountain summit. Nonetheless it quickly became evident in the early twentieth century that the local porters hired by Western expeditions were much better suited to high-altitude conditions than their clients. “If they are properly taught the use of ice axe and rope,” a Norwegian mountaineer wrote after a 1907 attempt, “I believe that they will prove of more use out here than European guides.” With proper technical training, Sherpas and Baltis could join in the achievements of the “sahibs” who employed them.

After Everest was conquered on May 29, 1953, all manner of challenges followed, including climbing the highest peak on each continent and climbing all fourteen mountains above 8,000 metres. The most prized routes shared a kind of minimalist aesthetic: blank, impenetrable walls and faces, serrated ridges plastered with icy cornices. Continuous cracks and fissures were viewed as geological “weaknesses” to be exploited.

Meanwhile, what McDonald refers to as “Mass Market Climbing” was taking over Mount Everest. Thirty years after Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s historic ascent, Laurie Skreslet and Patrick Morrow became the first Canadians to reach the top, in 1982 — the 123rd and 125th people to do so. As of January 2024, the mountain known traditionally as Sagarmatha — meaning “the head in the great blue sky”— had been climbed a mind-boggling 11,996 times by 6,664 different people. Every year, dozens from around the world show up at the Everest base camp without ever having pulled on a climbing harness or clipped into the types of ropes and cables that now run up to the summit. Inevitably, some experience nasty high-altitude side effects, which can be treated by inhaling bottled oxygen through high-flow regulators, by sleeping in hyperbaric chambers that control atmospheric pressure, and, in extreme cases, by receiving dexamethasone injections.

The majority of Himalayan ascents are made by Nepalis who own and operate or otherwise work for guiding companies like Elite Exped and Alpine Ascents International. There are also exclusive outfits like Seven Summit Treks, an agency focused on getting clients to each continent’s highest point, with what McDonald describes as a “fully commercialized approach” to climbing. Such commercialization has not been free of controversy. Consider these companies’ practice of hiring Sherpa guides, climbers, and support staff in the Karakoram, home of the Balti and Hunza peoples. The Karakoram’s remote and under-serviced peaks entail far more danger than those in Nepal; Pakistan’s tourist economy cratered following fatal Taliban attacks on eleven climbers in 2013, and the area suffers greatly from poverty and illiteracy. Yet few news articles about the January 2021 ascent of K2 pointed out that the celebrated climbers were not, in fact, from the local communities.

In 1985, a friend and I trekked in the Khumbu region, in Nepal. Our packs — we had planned a glacier crossing of the Thorong La Pass — were lightened considerably with the assistance of a porter named Mingma, a teenager from the nearby village of Thame. Over the years, I’ve thought of him and wondered if he ever joined the ranks of the so‑called Icefall Doctors, the courageous Sherpas who install the metal ladder bridges on Mount Everest. Perhaps he even climbed those famous 8,850 metres himself. McDonald points out that dozens of different Mingmas have made their marks in the mountains — because many parents name their children after days of the week — and thus in the Nepali guiding industry. I can only hope that, through it, the Mingma I knew escaped the grinding poverty that had made his country one of the world’s poorest at the time.

Outside the realm of mountaineering literature, McDonald is almost as anonymous as the dozens of Sherpas and Baltis she interviewed and profiled in this book — people like Mingma. Alpine Rising engages with courageous tales of ambition, triumph, suffering, and, yes, death. It deserves an audience as great as the mountaineering feats it celebrates.

Steven Threndyle lives a short hike away from Vancouver’s North Shore mountains.