Imagine you’re a scholarly sleuth researching a biography of the painter Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald and you’re reading his letters to friends and colleagues, his travel diaries, and his teaching notes from the Winnipeg School of Art. FitzGerald’s life and aesthetic ruminations begin to unfold with a 1930 note to his good pal Bertram Brooker and extend to a transcript of a CBC Radio talk from December 1, 1954. Some Magnetic Force brings such material and more together, along with a brilliantly concise introduction by the art historian Michael Parke-Taylor, who provides a helpful framework with which to explore a unique archive.

Having immersed yourself in decades’ worth of FitzGerald’s writings, you might begin to feel that you and the artist have been chatting for hours — as he often did with his friends until well after midnight. After all, you’ve been with him as he navigates his various roles as creator, teacher, lover, and public figure.

Some Magnetic Force is the fourth volume in Concordia University Press’s Text/Context series, which values artists’ writings “as compelling primary sources that illuminate artistic practice” and that “resist categorization and traditional narrative forms.” In other words, the series lets us hear what artists had to say in their own words — whatever form those words took. Launched in 2020, it specializes in “collections of essays, statements, articles, lectures, and other written interventions by Canadian artists, collating published and unpublished texts that are otherwise scattered, hard to find, or not easily accessible to readers.” It’s a laudable enterprise.

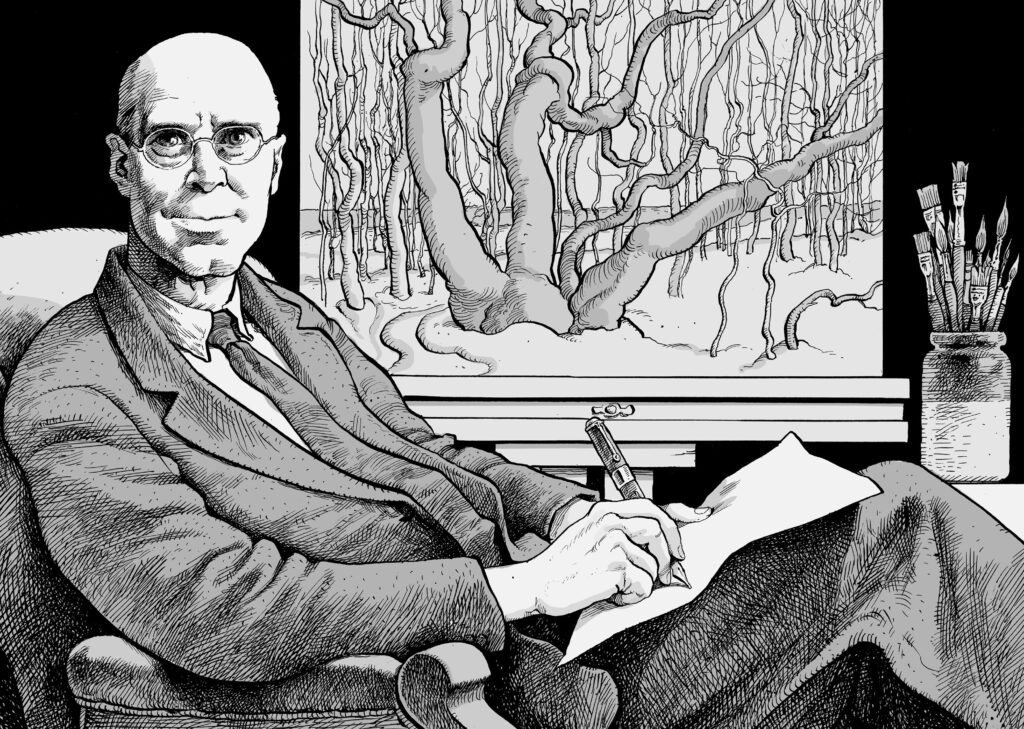

Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald was quiet in person but demonstrative in writing.

David Parkins

Given FitzGerald’s “retiring nature,” few contemporaries would have known what he expressed only to confidants or recorded for his own purposes. So it’s voyeuristic at times to read these documents, like his letters to Irene Heywood, with whom he began an affair in the late 1930s. These intimate musings are quite valuable. Significantly influenced by Cézanne, FitzGerald’s work can appear cerebral and self-conscious. His lack of inhibition with and desire for Heywood, then, is a revelation. Despite the surface decorum of his life, it’s obvious he was fuelled by powerful albeit hidden passions.

FitzGerald was a meticulous observer and a sincere correspondent. For readers who spend time with this collection, his art will resonate with a new, surprisingly personal poignancy. In many ways, FitzGerald’s writing is the antithesis of the opaque, laughably trendy art‑speak of so many of today’s artists, curators, and gallerists.

Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald was born in March 1890, in Winnipeg, where he died sixty-six years later. His life and art were rooted in the prairies, and most of his work, including landscapes, city scenes, and still lifes, has associations with Manitoba. Although he joined the Group of Seven in 1932 (FitzGerald was its only member based in the West), he was less preoccupied than the others with the search for a Canadian identity in the wilderness. Nature was of paramount importance to him, as it was for them, but in a different way. In introducing a letter FitzGerald sent to the abstract painter Bertram Brooker in 1930, Parke-Taylor writes, “The idea of feeling a connection with nature as a living force is something that Brooker shared with FitzGerald, although FitzGerald did not frame his beliefs in metaphysical terms.” Borrowing from the psychiatrist Richard Maurice Bucke, Brooker spoke of “cosmic consciousness.” Even as FitzGerald avoided such phrasing, his writings evoke a rather solitary character, a prairie mystic who wants his art to capture the unseen connections of the “eternal wonders that surround us.”

FitzGerald’s letters to Brooker were a cozy mix of day-to-day concerns and art theory as practitioners, rather than academics, discuss it. FitzGerald’s explanation of the “extreme delicacy” of his pencil drawings, for example, is touching. He credited “the terrific light we have here” and said that “the drawings always look strong enough when I am working on them outside, otherwise I wouldn’t be able to do them but when I get them home, they have the feeling of having faded on the short trip.” As a theme, the importance of prairie light emerges many times in FitzGerald’s writing.

In a 1935 letter to Brooker, FitzGerald confessed to a “peculiar feeling towards exhibitions of paintings that we have had here. It has almost amounted to a physical nausea at the thought of looking at paintings by the wholesale and I am afraid I am achieving a bad reputation for my apparent non-interest.” He asked Brooker, “Have you had such an experience[?] This has lasted for a considerable time now, and I suppose is just another of those experiences in life.” Here and elsewhere, their correspondence functioned as an artists’ support group by mail.

In writing to Harry McCurry, the assistant director of the National Gallery from 1919 to 1939, when he became director, FitzGerald focused more on business than on pleasure, though his own self-promotion was tactfully handled. The book’s title comes from these letters. The Group of Seven member Arthur Lismer’s departure to teach at Columbia University, in New York, prompted FitzGerald to lament Canada’s loss of some talented people — and to wonder why other artists, like him, remained. “Canada does not offer many rich plums to the artist but it does, for some unaccountable reason, seem to foster a great loyalty,” FitzGerald wrote. “Most of the artists are anxious to stay home, in much less affluent circumstances, just to be here. There must be some magnetic force at work that we are not aware of.” What might FitzGerald write today? For the ambitious, success in Canada is merely a good start. The magnetic force that once held artists here is barely detectable.

Composed between 1941 and 1943, FitzGerald’s letters to Heywood are almost a stream-of-consciousness combination of lust, art instruction, reportage, endearments, and nostalgia for their times together. “This morning just before I awakened,” he began in December 1942, “you walked toward me, naked, in a glow of light — all the space around you in light — light saturating the whole atmosphere — and you looked so beautiful.” The rest of the letter included tips about drawing technique, descriptions of his own current work, local art news, and other attempts to sustain his connection with a faraway lover. None of her letters to him have survived.

The book demonstrates FitzGerald’s sense of humour as well. In Report on a Little Journey around the Art World of Vancouver, 1944, prepared for the Winnipeg School of Art board of directors, the painter began, “Yes! Vancouver is different to Winnipeg. The streets have different names — Georgia, Burrard, East Pender, Belmont. Are not flat and level streets; they go up and down. Everyone walks just a little slower than we do, due perhaps to the undulations, perhaps it’s the climate or maybe the Vancouverites are just a little wiser than we.” An honest but kind assessment of the city’s art scene, its prominent artists, and its institutions, FitzGerald’s report is filled with knowing prose. “Good bits of painting, here and there, made the visit worthwhile,” he said of a large Jack Shadbolt mural. “No doubt most of the uneven qualities were due to the usual need for speed which so frequently haunts the mural painter and decorator.”

FitzGerald died of a heart attack in August 1956, leaving behind his wife of nearly forty-four years, the soprano Felicia Wright. For those who share something of his sensibility, so palpable in Some Magnetic Force, the art world today can appear a curious juggernaut — with artists, dealers, curators, consultants, media, auction houses, and major cultural institutions establishing brands and escalating values. That’s not to suggest that art consumption hasn’t always had status and money imperatives — think the Medicis. But the commodity aspect of art is now overwhelming. Going by his writings here, today’s stridently progressive and exclusionary mantras, along with identity-driven pedigrees, would almost certainly confound FitzGerald. Surely his quiet insistence on expressing his vision would be trampled in the current art mob’s scramble for packaged virtue.

Perhaps the 1940s and ’50s were a better time for an idealistic, introverted artist like him, especially when his friends could be supportive rather than competitors in a game of whose voice is allowed to be heard. Every generation has unique challenges for artists, of course. It’s naive, if not unfair, to think of FitzGerald’s moment as a gentler, kinder one, even if Some Magnetic Force gives that impression. Still, it is easy to be somewhat nostalgic for those years, when simple admiration for the beauty an artist created was why a collector wanted to live with their work. Back then, one didn’t reflexively judge an artist’s personal life or evaluate what they’d just posted on Instagram before buying a painting.

Kelvin Browne wishes Savannah weren’t in the United States — so that he could visit again.