A few years ago, the comedian James Acaster did a bit about the British Museum. He started by summarizing how it had acquired its collection: “Everyone in Britain got in a big old boat, and we set sail and we robbed (and this’ll sound far-fetched) everyone in the world.” Acaster went on to imagine a visitor from a former colony confidently arriving to reclaim some obviously pilfered artifact. “I don’t think so,” says the nonplussed Brit at the museum door. “We’re still looking at it.”

The routine (easily found online) sums up the prevailing view of the rotten ethical foundations of many collections. It’s more than fodder for stand‑up. For instance, the Australian and Canadian public broadcasters co-produced a successful podcast series, bluntly called Stuff the British Stole, examining the dubious ways many items wound up under glass in stately buildings. Indeed, curators all over are grappling with how to deal with tainted patrimony: everything from colonial-era plunder and items lifted from Indigenous burial sites to artwork linked to Nazi coercion of Jewish collectors.

Of all the arguments about museum treasure, though, nothing quite rises to the level of anxiety that surrounds the ancient Greek sculptures taken from the Acropolis of Athens and shipped to London in the early nineteenth century. Formerly known as the Elgin Marbles, after Lord Elgin, whose men did the taking, and now usually called the Parthenon Marbles, these masterworks have been the subject of such long and detailed disputation that their story illuminates almost every facet of the wider debate. So Alexander Herman’s judicious study of the still-unresolved wrangling over those ninety big pieces of sublimely carved marble, along with a few smaller fragments, provides timely grounding for a better grasp of the wider issues.

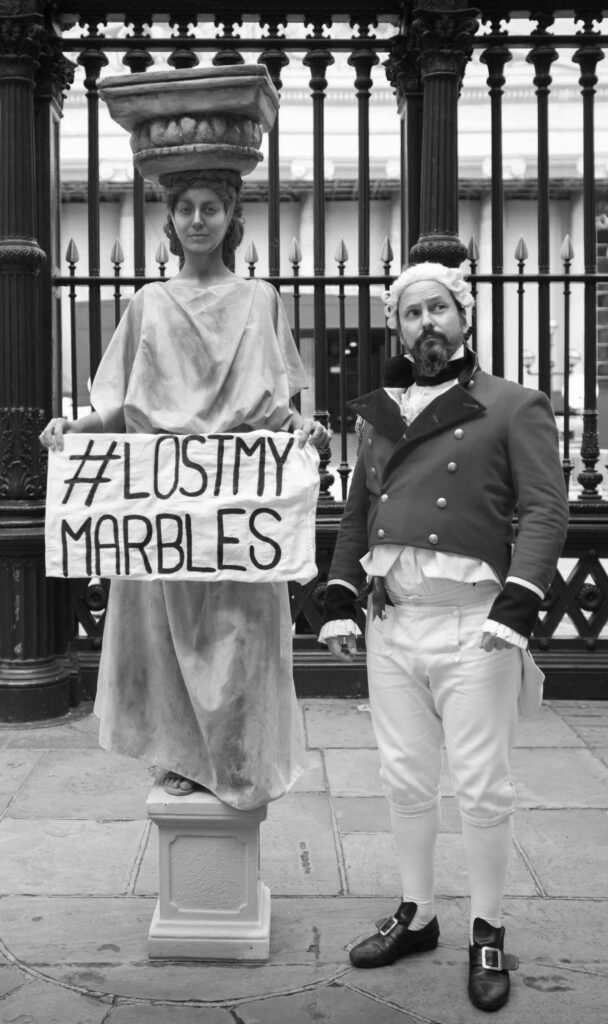

The latest act of a Greek tragedy in London.

Stefan Rousseau; PA Images; Alamy

For anyone whose opinion is shaped by the got-in-a-great-big-boat-and-stole-stuff school, Herman’s even-handedness might come as a surprise. Trained at McGill University and now the director of the Institute of Art and Law in the United Kingdom, Herman takes a lawyerly look at whether Elgin, who served as Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, obtained legal approval to remove the marbles in the first place.

In Elgin’s day, Athens was a minor town ruled by the Ottomans, its ancient glory long past, and the Acropolis a far cry from what UNESCO now calls “the supreme expression of the adaptation of architecture to a natural site.” Along with thousands of years of incremental deterioration, the iconic fifth-century BCE temple on the hill had been bombarded by the Venetians with cannon fire in 1687. “It is difficult to overstate the effect this event had on the Parthenon,” Herman writes, detailing how “the inner walls of the building were blown apart, the terracotta roof destroyed and 28 columns spanning the sides and entranceways, almost half the total number, were knocked to the ground.”

That doesn’t mean the marbles that decorated the Parthenon were just lying around. Only diligent finagling on Elgin’s part, greatly helped by Ottoman military alignment with Britain against the French, secured him a letter of permission to send a crew to work on the Acropolis site. Herman devotes serious attention to the status of this diplomatic note and concludes it amounted to authorization for Elgin’s men to haul away at least some material. The paperwork doesn’t “deflate the legitimacy of the argument for the restitution of the Parthenon Marbles,” he stresses, but it does suggest the debate needs to move beyond simplistic assertions that what’s in dispute here is a case of plain theft.

Given Herman’s legal credentials, readers might not expect the sensitivity he brings to questions far removed from parsing the clauses of Ottoman decrees. He writes lyrically about Mount Pentelikos, just fifteen kilometres from Athens, where the ancients quarried the stone for the great temple Pericles convinced them to build. He sits outside in an upscale suburb, “under a large pine lit by hanging lanterns,” to hear present-day Athenians explain in personal terms why “ancient heritage is central to modern Greek identity.” This claim might seem fanciful, but Herman gives contemporary Greece full marks for backing it up by teaching children their classical history, myth, and language.

A reader who happened to open The Parthenon Marbles Dispute to a page that has Herman gazing on old hillsides or lending an ear to Greek passions might assume he’s making the case for the marbles’ prompt return. Yet flip to the scene in the British Museum’s staff cafeteria, where he seems open to the opposite view. Underpaid workers earnestly discuss “how best to conserve, update and care for the collection in their custody.” They embody the beleaguered “universal museum” ethos of world culture. “I wondered how many other museums — or indeed what other workplace — would display such openness and comradery,” Herman writes.

He ends up proposing mediation based on statements of mutual respect: “for Greece to recognise the value of universal museums and for the British Museum to recognise the centrality of the Parthenon to the cultural heritage of Greece.” This might sound merely anodyne, but Herman’s diligent efforts to address thorny questions along the way lend his conclusions weight. How exactly were the marbles collected? What is their genuine relationship to modern Greece? Can the museum that holds them claim persuasively to be more than a hoarder of loot?

Variations on these questions need to be asked in many contexts. Earlier this year, for instance, some American museums shut down exhibits when the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act came into effect, requiring curators to ask tribal leaders for permission to display ancestral objects. There’s no parallel law in Canada, but our major institutions are grappling with similar issues, and in some high-profile cases they have given back artifacts to Indigenous communities.

Stolen property should, of course, be returned. Even objects obtained more legitimately might often be better showcased by their makers’ descendants. Dismissing the claims of the cultures that created the pieces in the first place has rightly fallen into deep disrepute. But switching to vilifying museums, though it can make for good comedy, isn’t much better. Herman’s fair-minded retracing of the Parthenon Marbles saga shows how — with plenty of clear-eyed research and sufficient goodwill — a far better balance is within reach.

John Geddes previously worked as the Ottawa bureau chief for Maclean’s.