Ottawa — once a frontier logging town and since 1857 the capital of what would become Canada — is not London, and the intricacies of the Canadian psyche are not those of the imperial British twilight. It is a challenge, given the thin and fragmented culture of this country, spread over a vast space and afflicted with intense, often intentional historical amnesia, to write a political thriller with the sophisticated richness and layered complexity of a John le Carré novel, the gloomy intricacies of Philip Kerr’s Nazi and Cold War Berlin, or the infinitely shady doings of Europe drifting inexorably into the Second World War as portrayed by Alan Furst. Historical amnesia is a great simplifier. We Canadians do not, as individuals, share enough collective memory to fuel, beyond the precincts of political junkies and the political class, a richly layered political narrative. Multiple ironies and allusions are lost if there is nothing there — or remembered — to allude to.

The lobbyist and policy adviser John Delacourt, a familiar of Ottawa’s halls of power, has often evaded this dilemma by placing much of his action abroad and piggybacking on deeper, more thickly overlaid traditions. He is the author of a series of intriguing, tense, highly erudite, and allusive fictions. Ocular Proof, from 2014, partly written in verse, is an intricate story of alchemy, art, forgery, and espionage set in Italy during both the Renaissance and the Second World War. Black Irises, a crime thriller that boldly mixes politics, art, and murder in a small Ontario town, appeared two years later. Butterfly, from 2019, mingles murder, art, and war in the context of the horrors of the 1990s conflict in Bosnia. And Provenance, from 2023, follows a Rome-based Interpol art sleuth, Christina Perretti, who, while tracking down works of art stolen by the Nazis, inadvertently uncovers a criminal art network that spans present-day Europe.

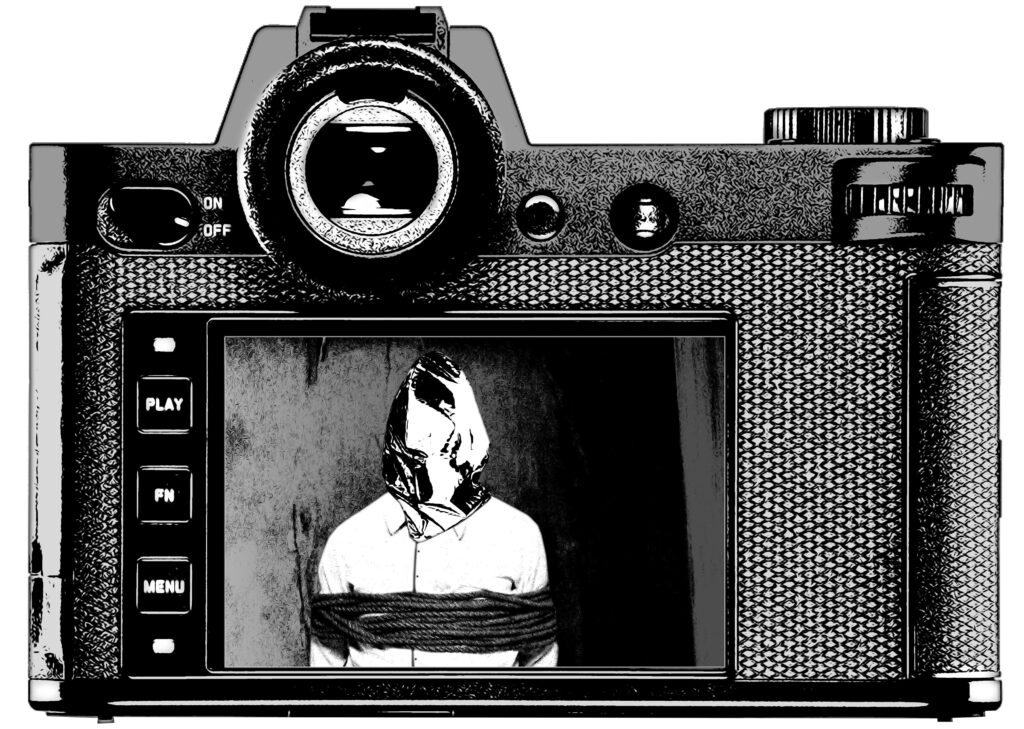

A cerebral artist becomes a despairing prisoner in this riveting novel.

Pierre-Paul Pariseau

Delacourt has now written The Black State, an ambitious political thriller that sweeps easily across a wide range of themes, including the complicity of the Canadian government in the worldwide system of “renditions” and “black sites” that the United States engineered as part of its War on Terror; the decay of ethics and professional standards at the top levels of the Canadian civil service; the role of Russian oligarchs and military thugs in global systems of oppression and corruption; the venality, opportunism, and cynicism of today’s political operators; and the ethical ambiguities, contradictions, and corruption of “high art” claiming to be an instrument of political militancy.

The novel’s protagonist is an extremely successful Canadian art photographer, Henry Raeburn, who specializes in photographing secret interrogation facilities where political prisoners are illegally kept. Pursuing his elusive prey, Henry sets off alone one morning in a rented Renault from Rabat, Morocco, to shoot a black site hidden in a forest in a southern suburb of the city: “Out here there was no country any more, nothing governing but the ancient wild. This old forest swallowed up everything, including time. What better place for a secret prison: the landscape of forgetting.” This black site is not fictional; it is the Temara interrogation centre.

Temara, which officially does not exist, has been in operation since the mid-1980s, allegedly financed more recently by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. It’s where, alongside the CIA, Moroccan security forces hold, interrogate, and torture political prisoners, presumed terrorists, and other undesirables. Henry turns such black sites, such houses of horror, into works of art. He is not a documentary photographer of blood and grime, however, and not a reporter. He is a cerebral artist. He wants to push his work “into abstraction.” His influences are old avant‑garde, European, sophisticated, and elitist. Here, we are in Susan Sontag land.

Years earlier, after seeing Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger, a 1975 film starring Jack Nicholson, Henry, a recovering drug addict with a record, had abandoned his video camera for a Leica: “The moving image, he decided, created an expectation of conventional storytelling. That was exactly what he didn’t want to do — and he had no interest in subverting the medium.”

As he positions himself on a bare square of rock to photograph the black site — exposing himself to great danger — Henry’s mind drifts to thoughts of Yasmin Raza, his love, an enigmatic lawyer and human rights activist whose family immigrated to the United States from Pakistan. He also reflects on his aesthetic philosophy. Although the site before him is most decidedly deadly and real, Henry, wielding his Leica, wants ambiguity and irresolution; he wants to attain that old chestnut of twentieth-century high art, Verfremdung, or making strange. It’s an effect often found in Antonioni, whose stunning sequences can make you experience emptiness and absence — existential meaninglessness, the irredeemably alien thingness of things — as you have never experienced them before.

By late afternoon, Henry has about “two hundred photos to pore over.” Tired from a full day in the sun, and with his mind still elsewhere, he heads back to his Renault. Suddenly a white SUV pulls up behind him: “The pounding of his heart surprised him; he thought he’d be less afraid.” Asked to get out of his car, Henry is handcuffed by a “surprisingly young” officer. Now a prisoner himself, he enters a world where he will experience, in the flesh, all the horrors and deprivations he has so often depicted from the outside, from a safe physical and aesthetic distance: “If Henry could intuit anything, it was that time was about to become more of an abstraction. Days might contract or expand, depending on the intensity of his loneliness. And perhaps his despair.”

Around him — around his case, anyway — a small galaxy of characters mobilizes. His father, the Conservative senator Gordon MacPhail, does what he can to rescue his son, initially in a rather floundering, ineffectual way. An Ottawa lobbyist, Ginny McEwan, who works for the leader of the opposition, tries to keep MacPhail in line; the scandal of his son’s arrest must not hurt the Conservative Party. Ashwin Khadilkar, the Canadian ambassador to Morocco and a corrupt operator with links to the Moroccan military and to a ruthless Russian oligarch, is not particularly eager to save Henry. Torquil Forsey, the son of the former Clerk of the Privy Council, hence part of an Ottawa mandarin dynasty, working as a functionary in Khadilkar’s embassy, is a highly principled gay aesthete living in the shadow of his late father.

Many of the characters in the book — Henry, MacPhail, Forsey, and even Henry’s estranged German mother, Marithe Heinemann — seem haunted by their fathers, whether their fathers are dead or alive. Oedipus hovers in the margins. In fact, personal passions, conflicts, and obsessions artfully provide the narrative depth and scope that, quite possibly, a rather thin or ahistorical Canadian political context could not alone have supplied.

Garry Fry is Henry’s London-based art dealer. Knowing that Henry’s misadventure and possible martyrdom will make his work even more valuable, he also rushes into the fray. Marithe Heinemann, rediscovering her suppressed maternal feelings, helps raise money for a ransom to save her son. Hannah Eisenberg, a Jewish lawyer and human rights activist, tags along and gives the senator moral support in his quest to save Henry. All these characters are swept up in a thrilling swirl of reversals, deceptions, and betrayals that reveal the deadly corruption of high art, the cynicism of realpolitik, and the immense collateral damage of the War on Terror.

The Black State is a riveting read. Just one quibble: the International Herald Tribune ceased publication on October 14, 2013, yet the characters, unless I am mistaken, are still reading it several years later.

Gilbert Reid is a writer for television and radio.