With his latest book, Mark Bourrie ushers readers into a world replete with exotic rituals, social and cultural habits long extinct (or, more precisely, obliterated by sovereign European powers), and not a few mutual slaughters. Gripping stuff, grippingly told. The book’s grand sweep takes us from the arrival of Jean de Brébeuf in Canada in 1625 up to the 1984 visit of Pope John Paul II, who prayed over the Jesuit’s skull, strategically positioned at the Shrine of the Canadian Martyrs in Midland, Ontario. There are some preliminaries, such as an ultra-condensed sixteenth-century history, as well as some updates on archeological excavations at the site where Brébeuf and several companions died in 1649. In addition, Bourrie provides a glossary of nations, places, and sundry other items, including a dramatis personae of near-Tolstoyan magnitude, to help us keep track of the many players who people the text.

The competing ambitions, savvy conniving, venal exploits, and ruthless tortures meted out to the unlucky are chronicled with meticulous detail. Bourrie spares little in recreating the world of New France, with its “reputation as a land of adventure and danger,” in the early to mid-seventeenth century. His minute-by-minute recounting of the Huron torture of the fifty-year-old Iroquois man Saouandanoncoua, for instance, makes for excruciating reading. In less skilled hands, it could count as torture porn.

It is critical to take note of the title of this book, Crosses in the Sky: Jean de Brébeuf and the Destruction of Huronia, as it clearly delineates the chronology and methodology that Bourrie deploys in his exploration of a mythic slice of Canada’s foundational past. The book is a history of the colonization of Huronia — the home of the Huron Confederacy, which consisted of several nations — and a biography of the Jesuit missionary Jean de Brébeuf. This mix of genres is both tantalizing and frustrating. When it works, it is arrestingly illuminating; when it fails, its deficiencies are egregious.

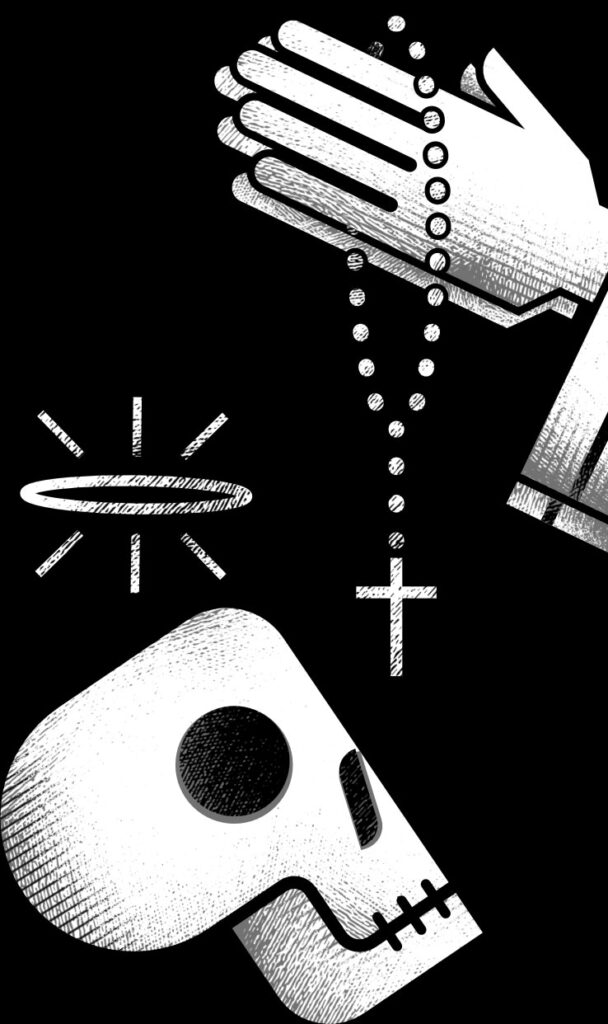

The martyr’s closet is full of skeletons.

Matthew Daley

At the outset Bourrie makes clear — and reinforces at other moments in his extensive endnotes — his familial connections with the Huronia-Jesuit narrative. “I grew up in Huronia and worked as a journalist in the region for thirteen years in the 1980s and 1990s,” he writes in his introduction. “I visited many of the Huron village sites listed in this book and could feel the history and beauty of Huronia. In many ways, it is still home to me.” Crosses in the Sky, then, is personal; its author is on a mission.

The Jesuits were engaged in a colonizing process — eliminating customs, languages, spiritualities, and social and cultural mores — with the intention of bringing the Indigenous peoples of North America into the Roman dispensation. In other words: convert, convert, and convert. Bourrie argues that the Jesuits’ tenacious efforts to baptize the damned before it was too late for their eternal souls, often in the face of grave personal danger, combined with the Hurons’ various military and commercial alliances to undermine their society, rendering it increasingly vulnerable to formidable and ancient enemies.

Bourrie knows that tribal rivalries and hostilities existed before the European incursion. Turtle Island was not El Dorado. The so‑called Black Robes — agents of the French imperium and the Roman sacerdotium — were, however, a new challenge. Unlike Roberto de Nobili in India or Matteo Ricci in China, Brébeuf and his clerical and non-clerical brothers were not inclined to adapt the Gospel to respect the cultures of their hosts, and the strife they created by imposing their own religious and cultural values had devastating consequences.

Bourrie relies heavily on the key primary sources, especially the Jesuit Relations, the minutely detailed chronicles and diaries sent by the Jesuits to their superiors in France that fill dozens of volumes, and The Jesuit Huron Mission: Latin Letters. In doing so, he skillfully allows his readers to grasp the fury, mad zeal, mindless brutalities, and quotidian realities on the ground. Bourrie’s painstaking analysis of competing First Nations, his intricate reconstruction of longhouse life, his natural sympathy for Indigenous approaches to sexuality, and his detailed list of the maladies that beset the various communities within the Huron Confederacy and the Five Nations — including cycles of famine and plague, a particular consequence of commerce and social intercourse with the European kingdoms — have a cumulative power that can occasionally veer between the admirably factual and the crushingly copious.

As a historian, Bourrie knows how critical it is to hear suppressed or extirpated voices, and to that end he religiously recovers stories that have been ignored or swallowed up by establishment narratives. He can be quite derisive of historical portraits — fictional and non-fictional — that he construes as triumphalist, biased, overly commercial, or simply inaccurate. Included among these are novels by Joseph Boyden (The Orenda), Brian Moore (Black Robe), and Franklin Davey McDowell (The Champlain Road), as well as the romantic works of the American historian Francis Parkman, who shaped for popular consumption what became the dominant mythology regarding Huronia and the Jesuits. He doesn’t mention E. J. Pratt’s once celebrated poetic epic Brébeuf and His Brethren, but one can easily imagine his assessment of it. Readers know where Bourrie stands. He pulls no punches when he argues for redressing the record, for challenging the official accounts that are not much more than orthodox renderings steeped in historical presumptions and Eurocentric biases.

Undertakings such as Bourrie’s are fraught with the potential for overreach and can be peppered with the scholarly sins of “presentism” and ideological reductionism. His sometimes laboured but always scrupulously fair treatment of the Indigenous parties in the complex political and cultural cartography of Turtle Island is the cantus firmus that holds his narrative in place. In this sense, Crosses in the Sky is a largely persuasive narrative.

Bourrie’s treatment of Brébeuf, the premier Black Robe in this story, is also faithful to the experiences recorded in the Jesuit Relations. And while he retains an appropriate agnosticism regarding the disinterestedness of the priest’s autobiographical accounts, he fails to include in the book any sense of Brébeuf’s faith.

If readers want to know what shaped Brébeuf as a Jesuit — the rigours of his intellectual formation and the central role of Spiritual Exercises, the foundational text of Jesuit spirituality — they will be sorely disappointed. Bourrie betrays his own peculiar take on this masterwork of Christian spirituality and the special role it played in the life of the founder of the Society of Jesus, Ignatius of Loyola, when he compares Ignatius to a “modern huckster.” He also likens Spiritual Exercises in its intensity to Scientology “courses,” in the process disclosing an astonishing ignorance of both Ignatius and his enchiridion.

Admittedly, Crosses in the Sky is not a study of the Jesuits per se, and insofar as it is a biography of Jean de Brébeuf, it is limited to his work in New France, culminating with his ill-conceived effort to establish a Christian colony in Huronia. Regrettably, however, the portrait of this Black Robe is part caricature, part bogeyman: a vessel for all that was wrong in the Jesuit efforts at proselytizing.

In his determination to write a secular biography of Brébeuf — to avoid what he considers the pitfalls of apologetic or hagiographical biographies and studies — Bourrie has done to Brébeuf precisely what he rightly condemns scholars and others for having done to Indigenous history: shorn it of context and judged it from a distance. For sure, the information available on Brébeuf’s early life is scanty, and the pertinent data is well deployed by Bourrie when it comes to his life as a missionary. What is lacking is a nuanced and layered appreciation of the religious “makings” of the Jesuit who perished in the wilds of a world very different from the Normandy of his youth.

Brébeuf was a product of his time, a child of a much different zeitgeist — of a France seared by religious acrimony, ruthless wars of attrition, court intrigues dominated by the formidable Cardinal Richelieu, and internal Jesuit squabbles. His cultural and religious language was of a particular moment and tradition. When he wrote of demons in relation to First Nations, he echoed the prevailing beliefs of his age, in which demons were fearsome entities doing combat with the soldiers of Christ. For example, when he returned to Huronia in 1634, following a three-year period back in France, his native country was wrestling with the most outrageous instance of demonic possession at an Ursuline convent in Loudun. That event has been the subject of a book by Aldous Huxley, a play by John Whiting, and a film by Ken Russell starring Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave. It’s much-covered territory.

So when Brébeuf’s horror of demons is described, it should not be treated as an obvious marker of aberrant behaviour. When Bourrie speaks of Brébeuf’s graphic dreams — in which he heard the language of the Book of Revelation, with its apocalyptic tropes, and saw mystifying images — he should read them as illustrative of the kind of devotional discourse with which Brébeuf would have been closely familiar, rather than as “symptoms of a serious and worsening mental illness.” Bourrie is right to contrast the general liberality of Indigenous sexuality with the more restrictive attitude exhibited by the Black Robes, but the implication that the Jesuits were Catholic Puritans is also wrong. In fact, they were denounced in France by their theological adversaries, the Jansenists, for being lax on carnal sins.

To put this all another way, Brébeuf was more — much more — than a martyrdom-crazed religious fanatic, headstrong zealot, and pious New France spiritual conquistador some 375 years ago. Although Bourrie admires Brébeuf’s personal courage and his remarkable gifts as a polyglot, there is little evidence that he actually understands his subject in the context of his subject’s own time. Rather, Brébeuf is cast as a symbol of the catastrophic failure of the invaders — secular and religious — who imposed “civilization” on the First Nations.

We live with that legacy daily, a legacy of eradication, of uprooting, of intergenerational trauma, and of historical amnesia. What Crosses in the Sky does well is refuse us a reprieve. And rightly so.

Michael W. Higgins is the author of The Jesuit Disruptor: A Personal Portrait of Pope Francis and other books.