The sins of the Harper government are well known. The party that came to power preaching accountability and ethics has instead done its best to undermine every institution of accountability that we possess, even as it slowly descends into its own ethical bog. The party that once stood for the rights of ordinary members of Parliament to represent their constituents is now the nearest thing to one-man rule. Not only are members of caucus bent to the leader’s will, unable to vote or even speak except as the leader and the whips decree, but Cabinet itself has become little more than the leader’s echo chamber. Gone are the days of powerful and independent-minded ministers, given a brief and left to get on with it. These days ministers’ offices are filled with people placed there by the Prime Minister’s Office, to ensure not only their loyalty but their single-minded devotion to the centrally determined message track.

The same tight control has been extended over Parliament as a whole, and throughout the apparatus of government. Much of the government’s legislative agenda for a given session is now commonly packed into a single omnibus bill, forcing MPs to vote on dozens of disparate bills at one go, without benefit of serious study in committee. Debate is now cut off on virtually all government bills, a procedure that was once so rare that, when invoked in support of a pipeline bill in the 1950s, it ignited the famous month-long parliamentary brawl known as the Pipeline Debate. On those rare occasions when serious scrutiny of its actions threatens to break out, the government prorogues. The standard of rhetoric expected of MPs and ministers alike has degraded to the robotic repetition of the same stale talking points, which more than ever before consist of attacks on the opposition. Election ads, likewise, have descended far beyond mere attack ads to a level of all-out personal abuse not previously seen in our politics.

Scientists and other civil servants find themselves under the same rigid gag orders as members of caucus. Those who have spoken up against the government line, or merely refused to spout a line they knew was untrue, have been fired or forced out. Even those public officials with institutional protection from such intimidation—parliamentary officers, such as the auditor general, the chief electoral officer or the parliamentary budget officer, or Supreme Court judges—have faced extraordinary public attacks on their character, their competence and their impartiality. Members of the press, private citizens though they are, have faced the same harsh treatment, as part of a larger campaign to freeze out, antagonize, manipulate and generally dispense with the mainstream media. Like virtually every other institution of democratic accountability, they have become the enemy.

All of this, as I say, is well known. After nine years in power, the record of the Harper government, on this as on other scores, has been exhaustively documented. The writer who wishes to tackle the subject in book form, then, faces a challenge. Rather than rattle off the same litany of facts, can he add something new to the subject? Some, such as the journalist Paul Wells or the academic and former Conservative strategist Tom Flanagan, have sought to explain it more fully, expanding our understanding of the government’s methods and motives, whether through in-depth research or their own insider perspective. They are making the first attempt to bridge from the blow-by-blow accounts of journalism to the more measured assessments of historians, and as such are obliged, even if they come to a critical conclusion, to view the government in the round, embracing not only its faults but also its virtues, its successes as well as its failures.

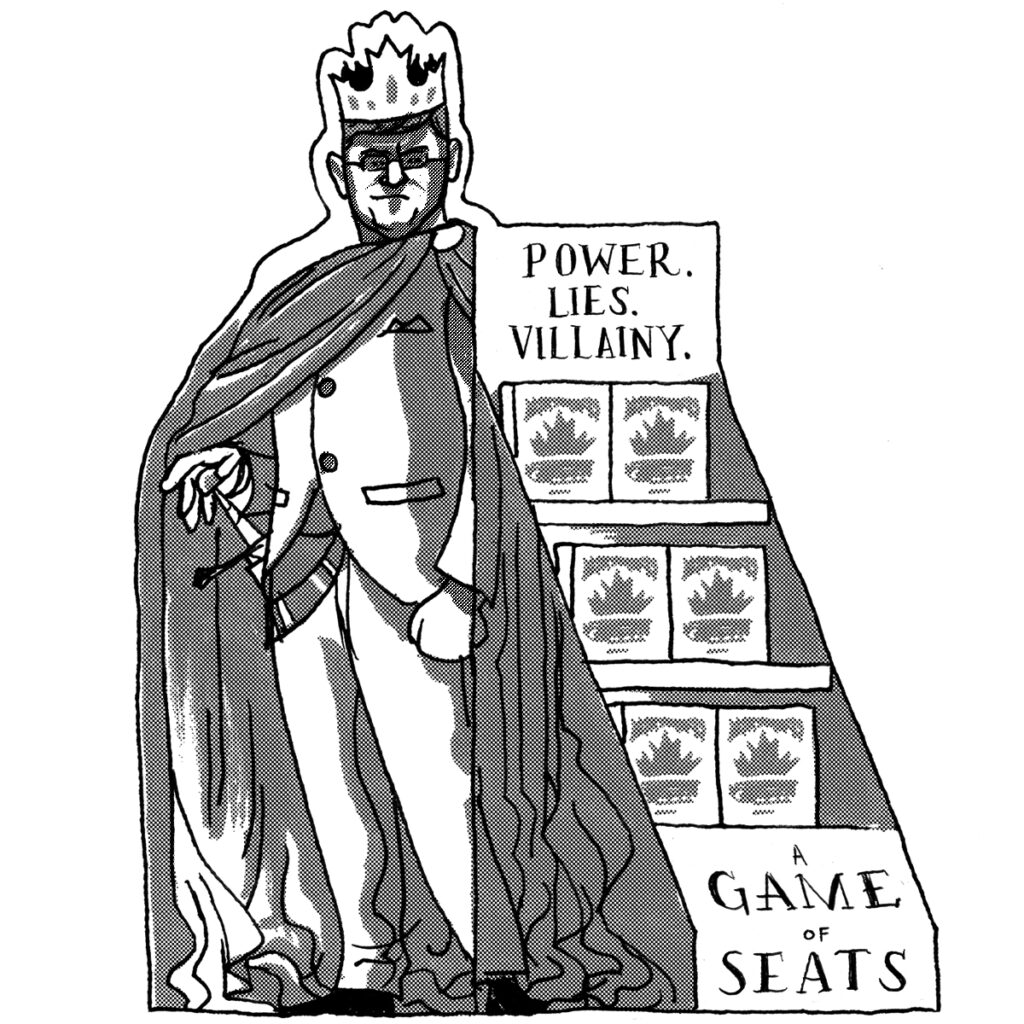

Drew Shannon

Others seek merely to indict. They are not interested in a balanced assessment, or the government’s record as a whole. They have a specific accusation to make: the government is guilty of x, and damnably guilty at that. There is a place for that, God knows, but it runs up against the limits of polemic. If they are not merely to add yet another recitation of the government’s sins to the pile, they are obliged to offer us something more. Perhaps a revelation: it’s worse than we thought! Or a solution: here’s how to fix this mess. At the very least, they can make it interesting: a touch of humour, a dash of poetry, something.

Alas, the writers of such tracts are rarely motivated by such concerns. Filled with righteous wrath, they are absolved of the need to hold the reader’s interest, or to do much of anything but repeat the same accusations. Typically thinly researched—a bundle of newspaper clippings, the odd interview—and hastily written, they have but one object, to assert that their subject is a singularly infamous example of whatever it is they wish to condemn. It is no criticism of these books that they are not the whole truth, since that is not what they pretend to be. But it is no defence of them that what they contain may be largely true. It is the book, not the government, we are called upon to judge: that is, do they tell us something new? Do they succeed in persuading us of something we did not already know or believe? And it is as works of persuasion that the two books reviewed here fail.

That is not to say that some readers will not find them interesting and enjoyable. If you are already firmly convinced the government of Stephen Harper is a uniquely malevolent force in our politics, an incubus sucking the life out of Canadian democracy, you will find lots in either book to remind you of why you believe it. But the reader who is not already so convinced—the reader on the fence, the reader who you would think it should be the object of the writer to reach—will be left unmoved. That is a common failing of this kind of book, and the books here fail for many of the same reasons.

One is a certain inability to define the thesis. Of the two, Mark Bourrie’s Kill The Messengers: Stephen Harper’s Assault on Your Right to Know, is closer to the mark in this regard. Through several chapters Bourrie, an Ottawa journalist and historian, hews broadly to the line established in the subtitle. There is a detailed, if not terribly insightful account of the decline of newspapers in Canada and their associated loss of connection with the reading public, leaving them prey to Harper’s efforts to bully and marginalize them. The government’s habitual secrecy, its suppression of contrary evidence (as in the long-form census fiasco), its keelhauling of dissenting civil servants, its muzzling of Parliament, even its aggressive use of government advertising would all fit under the same rubric.

But the longer the book wears on in its workmanlike way, the further afield Bourrie starts to wander. The War of 1812 commemoration, the defunding of this or that activist group, how much it cost to build the Communications Security Establishment Canada headquarters, the renaming of the Museum of Civilization: pretty soon virtually everything that Bourrie dislikes about the government has been shoehorned into the same thesis. The consequence here is not just overbreadth, but a blurring of the line between actual “assaults” on democratic governance, of a kind that might find general opprobrium and simple ideological disagreements: between abuse of power and mere use of power, albeit by a government whose policies he disagrees with. No doubt it seems incomprehensible to him that any government would, say, cut the grant of the Canadian Conference of the Arts, but not everyone will agree. To some that is what they elected them to do.

And, of course, the broader the assault, the more the book attempts a comprehensive assessment of the government’s record, the more the reader may be inclined to ask: isn’t there anything good they did? This is particularly problematic in Michael Harris’s Party of One: Stephen Harper and Canada’s Radical Makeover, which delivers neither the focused critique Bourrie fitfully attempts nor the sweeping survey of the subtitle, but rather resembles a kind of greatest hits collection of Harper-era scandals. There are a couple of chapters on the robocalls affair, told in exhaustive detail but ending, much as the scandal did, without conclusive proof of anything much. The F-35 mess is more usefully recapitulated, before we are caught up in a long, long exposition of the Duffy-Wright business: a sordid episode, to be sure, but hardly evidence of a “radical makeover” of the country.

Along the way we visit with various people Harper mistreated—Helena Guergis, for example—and a few of his more unsavoury friends, while dwelling on the complaints of critics such as Paul Heinbecker, the former career diplomat, and Paul Martin, the former Liberal prime minister, that the Harper government has not pursued the course they would have preferred in the fields of foreign affairs and aboriginal policy, respectively. This is closer to makeover territory, at least, and their not particularly unbiased criticisms may even be well founded. But the tendency to lump together honest policy disagreements with the government’s genuine or alleged misdeeds, the whole treated in the same scandalized tone, dilutes, rather than intensifies, the reader’s capacity for outrage.

This lack of perspective is common to both books. For all their obvious emotional investment in the subject, neither has taken the trouble to really understand the government, or the man, they describe. Even allowing for the limitations of the form, if you start from cartoonish assumptions you will end with simplistic conclusions. So we are treated to the same fervid references to the dark doings at the “Calgary School” where Harper studied 30 years ago—although in place of the ominous invocations of Leo Strauss that usually pepper these things, we are here treated to vague passes at Friedrich Hayek and the American political scientist William Riker as the mysterious sources of Harper’s evidently (to the authors) occult beliefs.

Bourrie at least gets it that the Harper that was is not the Harper that is: that the government he leads, and the choices it has made, are not the fulfillment of the Reform Party vision of his youth, but the repudiation of it. Indeed, if the prime minister has had to exercise such minute control of his caucus, or has felt he had to, it is precisely because the party and the government have strayed so far from what they once stood for: it is easier to get people to stay on message if it is a message they happen to believe, and not simply whatever the prime minister or his tacticians thought it clever to say that morning.

Bourrie, too, is at pains to point out at numerous points that much of what is most reprehensible in Harper or his government—the desire for control, the reductionist approach to politics, and so on—predates him, or is common to all political parties, or is in evidence across the democratic world, so much so that one begins to ask: then why the obsessive focus on Harper? Is it possible that there is nothing particularly special about the Harper government, that the damage they are doing to our democracy is not the work of strange and unsettling new ideologies, but of ordinary people with ordinary ambitions and resentments—objectionable, but fundamentally explicable—taking advantage of an institutional structure that had already been greatly weakened by their predecessors?

If Bourrie and Harris both succumb at times to hyperbole—Harris trots out Farley Mowat, for some reason, to declare that “Stephen Harper is probably the most dangerous human being ever elevated to power in Canada,” while Bourrie dots his prose with references to fascism, Hitler and Stalin—if they inflate Harper into something much larger than a two-bit autocrat, it stems from the same unexamined attachment to certain clichés about Canada, so ingrained that the authors become incapable of understanding how anyone could possibly disagree, or why it would even occur to them to try. “Until that moment,” Harris writes at one point, “Canada had been a secular and progressive nation that believed in transfer payments to better distribute the country’s wealth, the Westminster model of governance, a national medicare program, a peacekeeping role for the armed forces, an arm’s-length public service, the separation of church and state, and solid support for the United Nations.” Then poof! Harper brought down a Paul Martin budget. With the help of the NDP.

Bourrie, for his part, is incensed by the Harper government’s attempts to emphasize those aspects of Canadian history—our military record, in particular—that suit their ideology. He freely admits, in his usual way, that their opponents have done exactly the same thing—“since the days of Lester Pearson, Liberals and New Democrats had portrayed Canada as a ‘middle power’ … our diplomacy and our peacekeepers were said to be part of the country’s quest for social justice … this kind of framing of diplomacy (and history) linked the prevailing national identity to the Liberal Party.” Only it does not seem to count—for no other reason, it appears, than that he agrees with it.

For Conservative history, on the other hand, his scorn is unbridled, not to say unhinged:

Harper and his government have a view of Canadian history that’s based on a foundation of deference—to order, to the monarchy, to a British world view in which progress is perpetual, people accept their lot in life, and civilized white people tame the wild land and “savage” people. It is a world of Christians converting heathens, of darkness pushed back, of simple stories of heroics, where men are men and women know their place …

It’s also a view of history that embraces the kind of paternalism that breeds institutions like the Canadian Senate. It washes away struggles for gender and racial equality, the right of the working people for decent wages and working conditions, the survival of the French culture in Canada, and the need to set things right with the country’s Native people.

All this, from a mild Harper statement in favour of the Crown and its links to our constitutional history, including “habeas corpus, petition of rights and English Common Law.” Talk about killing the messenger.

Andrew Coyne is a Canadian political columnist with, and editorial and comments editor of, the National Post and a member of the At Issue panel on CBC’s The National.

Related Letters and Responses

Mark Bourrie Ottawa, Ontario

Paul Benoit Ottawa, Ontario

Carl Turkstra Hamilton, Ontario