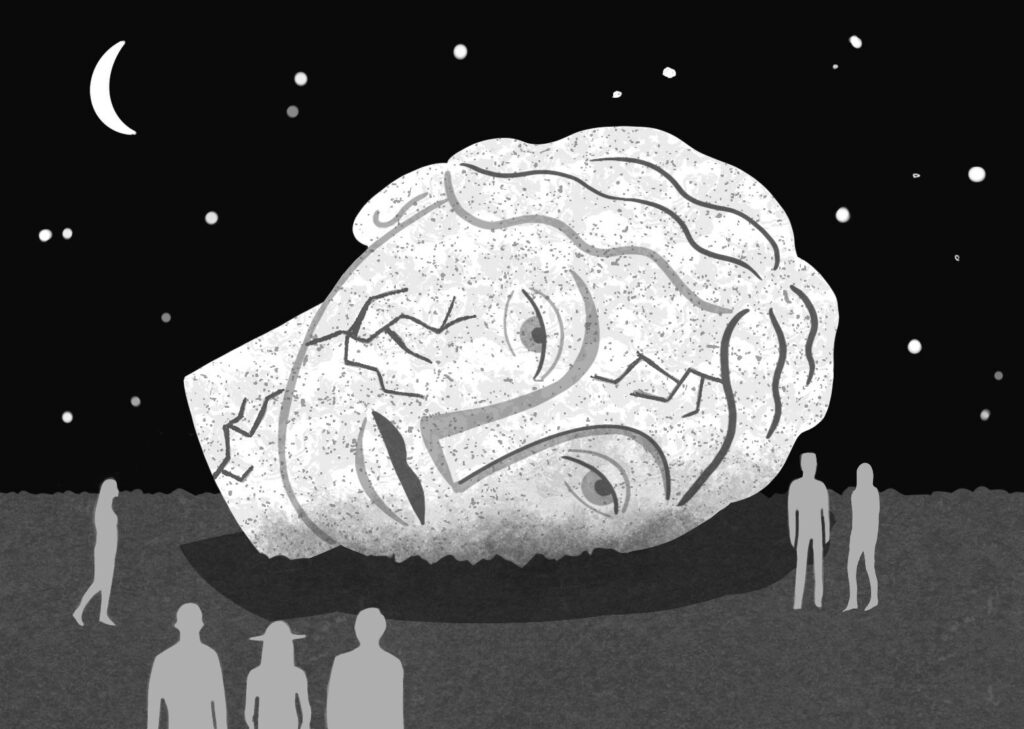

Writers are those naïfs among us who believe that language can be used to take the measure of experience. Readers demonstrate faith in them when they commit to a book or short story. The reader-writer relationship is a contract of sorts. But because the terms are not written down, there is much room in that contract for misinterpretation. What is at stake is not small: it is a shared picture of reality. Nor is it static. With each new publication or rereading, the reader-writer contract is up for review. What could go wrong?

In every closely examined work of creativity, no matter how successful, there is a frightening degree of illusion. Once, in an art gallery, I was taken with a work of Flemish realism depicting a man who wore the most dazzling lace collar. I moved closer and closer, until I could see that the fine textile was simply a series of crude white dots joined together by off-white and grey dashes. I walked backwards, away from the painting, while keeping my eyes fixed on it. Suddenly the lace collar miraculously and convincingly reappeared. For art lovers, such a thing is a marvel. For those looking for a simplified truth, it can be deeply distressing. Artifice is problematic for those who insist that all sleights of hand are meant to deceive, most likely for nefarious purposes. Is it any wonder that artists and writers in this age of mass media have looked to pull back the curtain on their practice?

What can one say in defence of writing? Because words can have multiple meanings, they are inherently ambiguous. The problem is compounded by sentences, paragraphs, chapters, whole works. Finding clarity of meaning often seems to require superhuman effort. So why bother, when all human endeavours fall short in one way or another, usually sooner rather than later? As someone famous once famously said, “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

Then the unthinkable happens — and the pedestal is pulled out from underneath them.

Jamie Bennett

Let me return to my initial statement: Writers are those naïfs among us who believe that language can be used to take the measure of experience. As an opening gambit, it is some shade of a red herring. No writer has ever taken the full measure of experience, nor will they. Also, writers write for all kinds of reasons. Frequently it is for escape or pleasure. Even writing that sets its heart on a truth — no matter how profound and serious — will still bear traces of these unstated motivations.

Readers read for the same reasons. Many people prefer imagination to reality, including those who have no interest in writing or reading books. Walking the streets of an isolated Canadian city, I see kids acting out hip‑hop fantasies, I see homeless men with tattoo-covered faces, I see strutting middle-aged men in Stetsons. “Reality,” to quote Philip K. Dick, “is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” This sounds like the truth, except that what remains derives as much from flights of fancy as it ever did from facts. The low-slung jeans and bling, the ink, and the cowboy hats are all equally real, as are the accompanying attitudes. Fantasy, diversion, and pleasure are key players in our understanding of reality.

What is this reality anyway, and how do we experience it? Instantly, the mind is a drunk man in a bathtub of grey water trying to catch soap with arthritic fingers. Reality is there and not there all at the same time. It reads, and it writes. Have you ever watched someone deeply absorbed in silent reading? They are present but also not. Something of their inner life is broadcast on their physical being. They may change colours, waxing to a blush or going pale as the narrative turns. Their breathing grows shallow. They bite their fingernails, sometimes drawing blood. They sigh, guffaw, moan. The abstract affects them as though it were a physical presence, that of another person or an animal. The experience is private, intimate even, but it can also form part of our public consciousness.

Mostly, reality allows you to passively interact with it. But then suddenly — seemingly unprovoked — it is in your face, demanding action. Such moments of change are often at the core of great literature. In these moments, reality reveals and even alters character. The skillful writer investigates, pulling apart such experiences to show the many and competing strands of reality and fantasy that they contain. The reader is given the chance to enter into another’s experience (while using their own experience to authenticate it) and to take on board the feelings and thoughts of multiple characters. It is an opportunity for both empathy and insight. That is not reality, of course. Such complexity is usually too much to handle in real time. It is overwhelming. We are paralyzed in the face of it. Often, all we can do is fall back on something called gut instinct — where unexpurgated wisdom meets untapped potential. We react because we have to. We do the best we can in the moment. Only time will tell if our response is adequate.

Like the reader lost in a book, the writer steps out of time when writing. And I argue that many writers are less equipped to cope with present circumstances than many of their civilian contemporaries. Being naive and sometimes overly sensitive, they see how unfair the world can be. The writer finds himself centre stage in a bruising moment of social life and fails to respond well, fails to come up with the bon mot, the piercing one‑liner that brings the bully to his knees. Fails to defend. Fails to protect. Fails to speak out. Fails to comport himself. Afterwards, he tries to brush it off but can’t. He tries to trivialize the exchange but finds that such efforts only make the memory of it more potent. That night, he walks home fantasizing about revenge, concocting other worlds in which he is the hero. Some writers take up permanent residence in that imaginative space. But many others take on that aforementioned task of pulling apart the episode in an effort to understand it. This work requires patience and a great deal of effort, as well as the ability to time travel.

We all want to be cast as the hero in our own narrative. No one wants to lie awake all night desperately reliving a scene in which they failed themselves or others. Weeks, months, even years can go by before we arrive at the eureka moment; suddenly we know what we should have said, understand what we should have done. Hindsight may be 20/20, but rather than liberate us, it can become yet another form of self-recrimination. Luckily, there is help. Great writers mind the gap for us, offering us a bridge across, a way of making sense. Robert Frost called every successful poem “a momentary stay against confusion.” If we are lucky, we can step out of our blocked contemplations and into the flow of right words. We might find in them some insight and understanding before we return to our private obsessions. Such writing can fortify and renew us. It can even free us from particular torments.

One who is capable of giving us this experience can seem special, righteous even. There’s the rub, of course, and where the rot begins to set in. The relationship between the person, the writer, and the author (three beings in one) is profoundly complicated. What makes a writer is a blend of technical skill, desire, and questioning intellect — the same attributes that drive excellence generally. Alas, the Romantic notion of the author as one of inspired virtuosity is still with us. Unhelpful are the many willing to ape this role.

Surely, the naive reader thinks, one who can write with enough precision to parse the complexities of experience is not ordinary; surely this excellence must also be present in all areas of their life. Having the courage to speak truth to power is seen as a moral good. Some readers bond powerfully with specific authors, particularly when they give voice to a reader’s private world, their domestic and inner life. Somewhere along the way, those writers can become moral touchstones.

In a time of funded readings, festivals, interviews, and a host of other public events, there is ample opportunity for readers — should they wish it — to meet living authors. That the experience is so often disappointing should be the first clue that the reader’s expectations are off the mark. Odd stick. Very shy. Not what I expected. Cold. A malign force of nature. Inscrutable. A loose cannon. Fake. Different. Rude. A charlatan. These are just some of the negative descriptors I have heard used to describe writers once met. Still, such judgments are often brushed aside when the next brilliant book comes out. That author was probably just having a bad night. Book tours must be exhausting. So many expectations to meet. Slowly, and then all at once, the author is returned to her pedestal.

But then the unthinkable happens. The writer is publicly accused of some serious wrongdoing. It might be criminal, in which case prosecution should happen. More often than not, however, the behaviour is not so much unlawful as it is indicative of a moral failing: unwanted sexual advances, plagiarism, the betrayal of trust, cowardice, hypocrisy, or simply acting as a person in a way the reader dislikes.

Again, those writerly types are often the least capable of coping with real life. In their real-world confusion, they turn to words and arcane forms of composition. They don’t necessarily understand why they do that and just as often don’t know if their response is a failing or a strength. Some observers describe the creative temperament as pathology. While the diagnosis may be accurate in some cases, it is generally wrong. Why then do writers write? Is it to redress those aspects of reality that feel autocratic? Is it to make up for a private failure in the face of such pressure? Is it to deconstruct societal definitions of reality that leave us feeling as if we are living in someone else’s bad dream? Who’s to say.

Generous writers draw deeply on their experiences, which often cross over into readers’ experiences. Overly generous readers think of writer and book as one, personality and persona as interchangeable. A large number of readers believe that the social, moral, and artistic excellence found in a book is indicative of the person who wrote it. This is rarely — if ever — the case. Hence the shock when one held in the highest esteem is suddenly shown to be morally if not criminally liable for some wrong. Certain readers will feel like fools. It is upsetting to learn that the vaunted universal appeal of the work — all that gritty realism — was not pulled from thin air. Others will make their disaffection public (the author has betrayed us!) and may even call for the writer to be shunned, their books to be burned. There are also those who, while not giving the writer a free pass, will go back to the work with a different lens and find whole new threads in the complex tapestry.

Patrick Warner has written three novels and five collections of poetry. He lives in St John’s.