Poor Justin Trudeau. The guy has never been able to catch a break. The house he grew up in had so many silver spoons in the kitchen drawer, he didn’t know which one to put in his mouth. His dad wasn’t around much, given that he was arguably the most famous Canadian in the world in the 1970s (with a side hustle as prime minister). Not to be outdone on the fame thing, Justin’s mom ran away and partied with the Rolling Stones when the tyke was in grade school. After years of home-front drama, Justin finished a bachelor’s degree and moved to the West Coast to teach — what else, drama. As a young man, he seemed to focus primarily on attending the least politically correct parties possible. After talking himself into entering politics, he convinced enough Canadians that great hair with a magnetic smile was the same thing as depth, and bang — he was running the country. Which was when his real problems started.

Now, nine years into his tenure, the custard seems to have set around the opinion that Justin Trudeau might not be the worst prime minister we’ve ever had but neither is he anywhere close to the top tier. He’s had a few wins as PM — negotiating NAFTA 2.0 and on child care, gender, Indigenous, and environmental issues (though with some qualifications on the latter two files) — but he’s also struggled to drive straight along two major avenues of activity. The first is inductive performance, the stuff we can directly point to. He has racked up or had revealed a string of boneheaded moves that would leave most sensible observers wondering how he’s managed to remain in office. The SNC‑Lavalin and Jody Wilson-Raybould affair. Vacationing on the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Wearing traditional garb in India. Being exposed for his various brown- and blackface escapades. The WE Charity scandal. Fumbling the election interference issue. The cynical pandemic election call. The mishandling of the two Michaels and the Chinese government. The multiple posh vacations at the homes of billionaire friends. It’s quite a list.

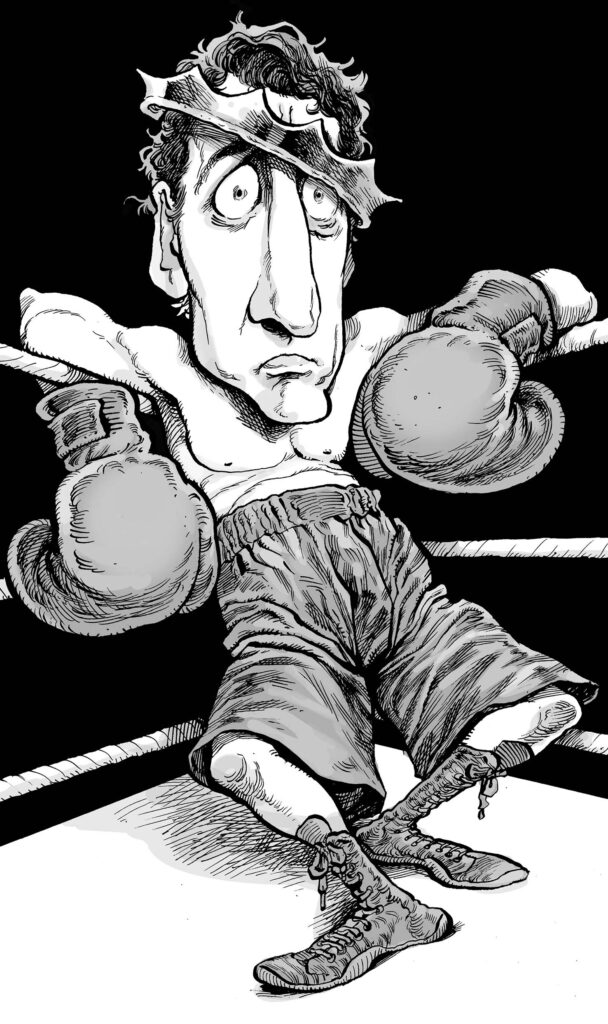

Round after round he goes.

David Parkins

But the second lane of failure, while less measurable, is more powerful and therefore more damaging. There are fancier and more intellectual ways to put this, but basically it’s about the vibe he creates. Positive energy was clearly what won him his first and, so far, only majority. The vibe he gives off now is cringeworthy. His manner of speaking is sanctimonious, his words clichéd, his smile static, and so many of his actions seem performative, inauthentic. One watches Trudeau today and sees an actor struggling to sell a role. Canadians went with it for a while, possibly because even Trudeau himself believed he was perfect for the part of PM, but now the cracks are showing, and that smile looks more panicky than pure.

All these and various other factors taken together have created a vessel most Canadians don’t seem to really trust, a craft with a sail made of suspect judgment roped to a mast of situational ethics — which is not what we want to be aboard on turbulent seas. Justin Trudeau has consistently fallen short of providing strong liberal or Liberal government, but he might be the luckiest politician on earth, given the weak Conservative opposition he has faced during his three electoral victories: Stephen Harper had emptied the goodwill jar, Andrew Scheer was anonymous, and Erin O’Toole was impossible to imagine as PM. This trend continues with the disagreeable Pierre Poilievre, who, if he had any sense, would just keep his mouth closed and let people focus on Trudeau; it would be his best chance to take power. Trudeau is also fortunate that Jagmeet Singh wants to keep his job by avoiding an election, though he’s ripped up the NDP’s supply-and-confidence agreement. Trudeau even has history and the national disposition on his side. Canadians tend to be centrist and lean toward compromise, an inherently liberal position. Were Canada a more right- or left-wing country, Trudeau would most likely have been ousted a long time ago.

Fortune and favour will take you only so far, of course, and two books make the case that Trudeau appears to have run out of both. The Prince, by Stephen Maher, and Justin Trudeau on the Ropes, by Paul Wells, explore the increasing likelihood that Trudeau’s political life will end not with a bang but with a whimper.

Stephen Maher is a veteran Ottawa journalist and has ample credibility and experience when it comes to dissecting parliamentary hijinks. He has written for Maclean’s, among many other outlets, and has won a variety of awards over the years. His time on the Hill gives him a strong platform from which he can both dive into the weeds on the many successes and struggles of Trudeau and assess him from a wider perspective.

In choosing his title, Maher is not so subtly drawing the comparison between Trudeau and the prince of Niccolò Machiavelli’s famous treatise. He quotes that historic text and refers to Trudeau’s princely behaviour at more than regular intervals. This causes problems early. The first reference to Machiavelli comes in the book’s epigraph, which reads in part, “Only an exalted prince can grasp the nature of the people, and only a lesser man can perceive the nature of a prince.” It’s as if Maher is saying that Trudeau alone can understand the electorate and only Maher can understand Trudeau.

This is a curious way to begin a book, especially when raising the spectre of Machiavelli’s dark, subversive, and complex work. The Florentine philosopher’s argument, radically boiled down, is that the ends justify the means to remain in power. It can only be that Maher wants us to assume that the portrait of Trudeau he is about to paint is that of a knowing, shrewd, cynical, ruthless, and, yes, Machiavellian politician.

Which is fine. But that’s not the book Maher writes, at least not exactly. We regularly hear stories of Trudeau’s naïveté in various moments, of his optimism, of his desire to do things right. If anything, the portrait that emerges is more that of a person who entered politics as a “sunny ways” true believer and evolved, or devolved, into a more cunning and narcissistic partisan.

Maher’s book works best when he avoids over-analysis and instead takes the reader deep into Ottawa’s backrooms and corridors of power. This is a world we rarely see as ordinary citizens, a world of power and relationships and hierarchies, of both grand vision and petty small-mindedness. We don’t hear only about Trudeau: we hear about Gerald Butts, Katie Telford, Bill Morneau, Jody Wilson-Raybould, and many more. Maher is fair-minded and gives the prime minister credit where he deserves it (or lucked into it). His overarching thesis is that Trudeau is a gifted performer, a man with genuine magnetism before a crowd, but who all too often keeps to himself. We hear such shocking anecdotes as the fact that even his closest cabinet ministers have not always had access to him and are unable to reach him directly when needed. Although able to withstand the worst barrages of criticism from political opponents, he has been notoriously thin-skinned when it comes to hearing from his own staff.

It’s a great set of tales Maher has to tell. None of it is new exactly, but the research, connections, reporting, and overall background work are impressive, and that alone makes The Prince worth reading. Do you wonder why Trudeau has had such inconsistent relationships with his ministers over the years? Maher illustrates how difficult Trudeau finds it to sustain personal relationships. Do you want to know what Trudeau was deliberating about when dealing with Jody Wilson-Raybould? Maher fills in the gaps. It’s a book full of inside dope, and Maher seems to have extraordinary journalistic access to the main players in Ottawa.

That’s not to say this is a perfect work of political journalism. The book’s many strengths are diluted by a variety of weaknesses, the first being the belaboured Machiavellian prince references. One or two nods would have sufficed; I stopped counting at a dozen. Maher’s sourcing and attribution is also problematic; while not untrustworthy, it does raise questions — questions that disrupt the flow of the narrative. Maher regularly makes assertions, relates stories, and offers quotes without supplying his direct source. The anecdotes always carry the ring of truth and buttress his primary narrative. And yes, Maher does caution us in his endnotes that many of his sources agreed to comment only with the assurance of anonymity. So he is doing the right thing by protecting his sources. But he leaves it too open-ended in the flow of the story. We still need to have a sense, as readers and citizens, of where all this material is coming from. What level of person are we talking about? What department? Where and when did the author talk to his sources? There are ways to contextualize conversations and interviews to give them validity, thereby removing the niggling questions that many readers will have. A magazine such as The New Yorker handles sensitive conversations with protected sources all the time, usually by supplying us with information as to the source’s stature or relation to the moment. Maher doesn’t do this. And too often the vagueness becomes a speed bump that temporarily interrupts the reader’s engagement. Numerous times throughout the book, I found myself stopping and thinking, “Okay, but how do you know that?”

Nor is Maher a great stylist. The sentence structures are rudimentary. The language is basic. There are few graceful similes or analogies, and those he attempts (Trudeau the prince) are overcooked. To be fair, Maher is a newspaper reporter, not Margaret Atwood. He’s not pretending otherwise. His book has an old-school journalistic carpenter’s trustworthiness to it, but there are enough sloppy moments to make one withhold full admiration. He uses the word “acclimation” at one point, when he means “acclamation.” There are verb tense inconsistencies. He pens mixed or clumsy metaphors, such as “Liberals had to get out of the way of the dumpster fire headed their way.”

There is also the occasional foray into solipsism. Regarding Trudeau’s assertion that he’d move Canada to proportional representation should he win a majority, Maher states, “I reported his comments, but I did not believe him — and, as things turned out, I was right not to believe him.” Sentences like this blur the line between memoir and reporting. Are we meant to be reading The Prince to understand Maher’s journey or Trudeau’s? Both are interesting, and both are valid. But the tone, grammar, and structure make this a rather confusing read at times, as if Maher and his editors knew they had good material on two counts but couldn’t decide which to focus on.

Less than a paragraph into Justin Trudeau on the Ropes, readers will realize they are in the hands of a very different writer than Maher. Paul Wells immediately places us at the deeply underwhelming start of Trudeau’s political career, in a moment of real crisis for the Liberal Party — shattered by Stephen Harper’s demolition of Michael Ignatieff. “Surely,” Wells writes, “the Liberals needed their best talent in crucial roles. Yet the party’s interim leader, Bob Rae, had appointed Trudeau his critic for youth, post-secondary education, and amateur sport. Since Parliament never debates youth, post-secondary education, or amateur sport, on most sitting days Trudeau’s attendance was strictly optional.” Two pages later, Wells describes the environment in which this young MP had grown up:

Trudeau has trafficked all his life in the currency of attention. Go ahead and look at him. People have been staring at him all his life. And whatever you think while you look, whether your reaction is awe or disappointment or the purest contempt, all I can tell you is, you’re not the first. Somebody else had the same reaction long before you came along. Somebody else will have it after you leave. Attention is the medium through which he moves. It is his luminiferous aether.

Quickly, we have a rich sense of who Justin Trudeau is, or at least who the author thinks Justin Trudeau is. Wells does a masterful job of setting the stage for the black comedy to follow, which is no surprise, given that Wells is as much an Ottawa veteran as Maher, though primarily as an opinion writer and pundit. His credentials are deep. In fact, one of his earliest in-person experiences with Trudeau was when he moderated the first televised debate between Trudeau and Harper.

Wells’s book is the quicker read of the two and the more insightful, even as it eschews the impressive primary research of Maher’s approach. Where Maher is sober-minded and inductive, Wells is sardonic and impressionistic. There might not be a single joke in all of Maher’s book, and there might not be a single page in Wells’s without one. Wells is also hunting different game than Maher. He makes no claim to be writing a work of definitive journalism or reporting. His book is in fact a long essay of just under 100 pages, which frees him up from the burdens of attribution and sourcing. This also allows him to draft more of a Freudian character study than governance analysis.

Whereas Maher exploited the prince analogy, Wells relies on the boxing metaphor, which is fitting given how much Trudeau has leaned on his 2012 boxing match with the Conservative senator Patrick Brazeau to bolster his confidence and legend. Here again, we get the pleasure of Wells’s willingness to offer insight into Trudeau’s character:

The image of Trudeau leaning against the ropes and taking his whacks is apt for another reason: because for all his pedigree and physical grace, the work of politics has never come easily for him. He is more intelligent than a lot of people are willing to believe, and at least as charming as you’d suspect, but he is no great public speaker or gifted debater. His judgment is often terrible. He has not surrounded himself with great talent; in fact, he has discovered a real gift for chasing talent away.

The picture of Trudeau that emerges under Wells’s precise eye is that of a man with a real but limited skill set who found himself sitting in the highest office in the land and has always struggled to feel comfortable there, moving from optimist to realist to someone who says he believes in collaboration but shows no evidence of following through on that belief. Wells writes that the cynicism was so bad before the 2021 federal election, Trudeau might as well have “taped a sign saying OPPORTUNIST to his forehead on his way to Rideau Hall.”

In many ways, the story Wells relates is one of pathos, not cynicism, that of a man who could have been a game changer but who let the game change him instead. Wells, for instance, gives Trudeau ample credit for renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement amid the chaotic circus of the Trump presidency. It was a successful effort on Canada’s behalf, but Wells questions why such statesmanship and competence haven’t surfaced more often. “I sometimes wonder,” he writes, “what would have happened if Trudeau had picked five other big intractable problems and applied the same level of ingenuity and concentrated effort on them. At least he picked one.”

The chief take-away from Justin Trudeau on the Ropes is that the prime minister’s main problem is character-related rather than tactical or strategic. It’s the story of someone who is capable of both extreme callousness and penetrating self-awareness, someone who sees his weaknesses and who “is an introvert who has become skilled at pretending the contrary.” As Wells states bluntly, Trudeau is “a mixed bag.” Apropos of the Liberal government’s handling of COVID‑19, Wells notes that a staffer once told him that Trudeau gets big things right and everything else wrong. He did well with NAFTA and the pandemic but bungled everything else. Justin Trudeau has “built a government that can’t stop announcing bright new days, even though it seems increasingly unable to deliver.”

Neither Maher nor Wells leaves the reader feeling optimistic about Justin Trudeau the man or the politician in what both describe as his political end times. These are harsh character indictments, but, as they say, politics is not for the faint of heart. Readers would do well to spend time with both books, since they arrive at their conclusions via different routes and each offers what the other does not. Maher’s might leave you hungry for deeper analysis, while Wells’s may have you craving more reporting. Reading the two as a linked set should satisfy the desire to learn more about the what and the why. Wells has written the more enjoyable book, but Maher has produced the one more likely to be cited in future political science dissertations.

And where do these writers expect Justin Trudeau to go from here? Maher does not offer an opinion but makes it clear that he does not see Trudeau changing in any substantial way. As for Wells, it would be possible, he writes, “to imagine Trudeau coming back yet again if he had lately shown any inclination toward introspection or humility, or a driving urge to improve his game.” Which, Wells opines, he has not.

That doesn’t mean he can’t or won’t win again. Canadians are already tired of listening to the scratchy broken record that is Pierre Poilievre, which means he might very well become the fourth Conservative leader Trudeau beats. The shame of it all, Wells argues, is that what Trudeau promised when he first came to power — transparency, simple competence, smart decisions — are the same basics that Canadian voters still crave. Trudeau, he says, has abandoned those things in favour of turning every challenge he sees, big or small, internal or external, into a boxing match, an opponent in the other corner, a thing to be defeated. He’s lost whatever ability he once had to tackle complex problems with innovative solutions and has become a blunt instrument. It’s worked, if measured only by his stay in power. If you go by other standards, such as sound government, ethical behaviour, good judgment, collaborative citizenship, and respect for your peers, then the grade is much lower.

Notwithstanding Joe Biden’s decision to suspend his final presidential campaign, it’s hard to remember the last time a politician in a democracy retired at the appropriate moment — when they could say they went out on top, had completed what they set out to do, or possessed enough insight to recognize they had simply run out of juice. Politicians tend not to see the writing on the wall. In fact, they usually walk face first into the wall. It’s difficult to say what will become of Justin Trudeau in the near future. When he finally gets the axe, the blow will most likely be delivered by his own party, not by the electorate. After all, most Canadians have already told Justin Trudeau what they think of him and yet, somehow, he’s still our prime minister.

Curtis Gillespie has won seven National Magazine Awards for his writing on politics, sport, culture, and science.