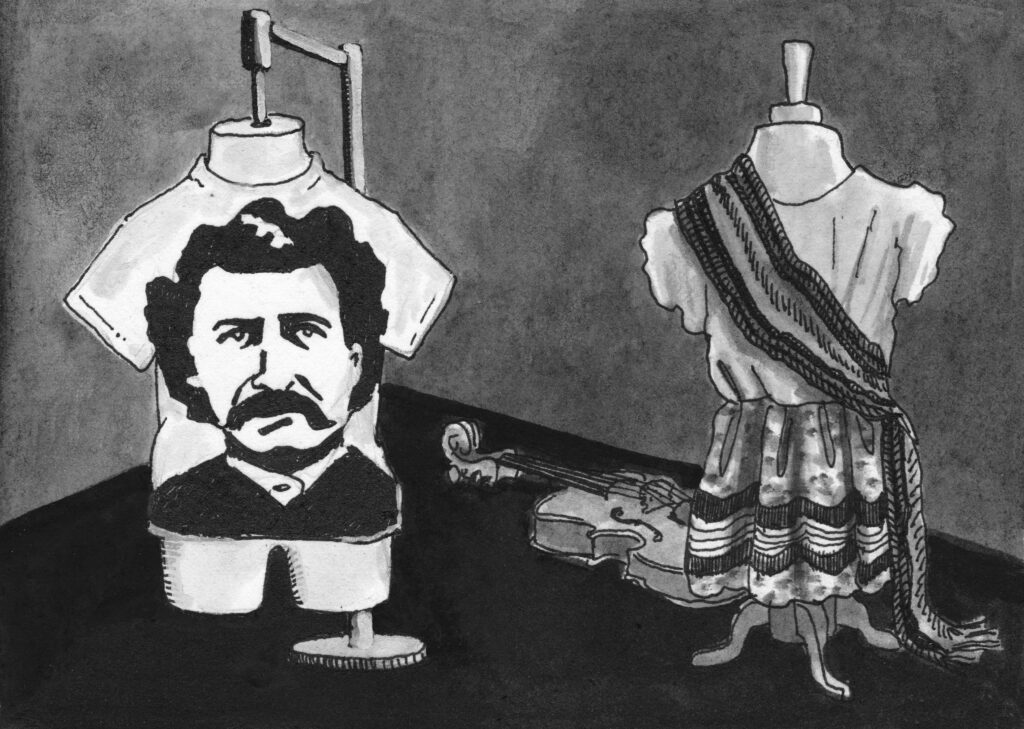

In December 1885, John A. Macdonald predicted, “The Riel fever will I think die out. If not it will be the worse for those who keep the fever alive.” Of course, the Riel fever did not die out. The website Way Back Winnipeg recently stocked the classic “Keepin’ It Riel” T‑shirt with Louis’s portrait — monochrome black on red. The print-on-demand marketplace Redbubble offers a pop art T‑shirt (six coloured Louis panels in the Andy Warhol style), cartoon stickers, and socks with Riel’s face and the Métis infinity symbol. There are two operas (I’ve seen both), the more recent one sung in five languages, including Southern Michif, French-Michif, and Anishinaabemowin; two statues in Winnipeg, including the controversial Marcien Lemay depiction of a naked Riel in ecstasy or pain (I’ve seen both); poetry and fiction aplenty, including Rudy Wiebe’s The Scorched-Wood People, from 1977, and Chester Brown’s graphic novel from 2003 (honoured with a stamp last year); and, of course, Riel’s tourist attraction of a grave, near his father’s, in St. Boniface. It’s only a few dozen feet from Avenue de la Cathedrale. You can take a picture of it from the car. Many do.

In Canada, for the most part, Louis Riel is a hero, or at least a figure of great excitement in a nation with a relative shortage of them, other than hockey players and Drake. He’s a northern Che Guevara and the honorary first premier of Manitoba, according to an act of the legislature. He founded a provisional government on the Red River in 1869, fought for his people, and was hanged for high treason in 1885, dying as a myth and a martyr. But there’s the paradox: his metamorphosis from enemy of Canada to one of the country’s most admired figures (ranked eleventh in the CBC’s Greatest Canadian contest, beating out Stompin’ Tom Connors at thirteenth, Nellie McClung at twenty-fifth, and John Diefenbaker at a distant forty-seventh) is remarkable, ongoing, and in some cases problematic.

A T-shirt doesn’t begin to capture the complexities of historical or contemporary Métis culture.

Silas Kaufman

That metamorphosis and its impact are the subject of Albert Braz’s The Riel Problem. A professor emeritus with the University of Alberta’s Department of English and Film Studies, Braz maps out Riel’s evolution in modern times, mostly through culture and art, but his real purpose is to examine how the burnishing of Riel’s image (like that of Che, now forever on a shirt) has been a distraction for Métis artists and intellectuals for whom the mythology gets in the way of the contemporary story of their people. In the words of the Métis poet Rita Bouvier: “I want to scream. listen you idiots, / Riel is dead! and I am alive!”

Braz’s book, academic in structure and tone but accessible, takes its subject seriously. In fact, Braz is something of a career demythologizer of Louis Riel, with this volume following The False Traitor: Louis Riel in Canadian Culture, from 2003, in which he wondered why non-Indigenous Canadians are so fascinated with a Métis leader. Riel is the underdog, Braz reasoned, and he feeds a Western fascination with the Great Man Theory of history, wherein complicated stories can be carried by a central dramatic character. He’s also a throwback to Greek mythology — not just the heroes but the villains too (Desmond Morton called Riel the “modest Canadian counterpart” to the Ayatollah Khomeini). In this new book, Braz aims his sights higher: Riel may be a pop culture hero, but what happened with his ambitions to protect and enshrine the rights of the Métis on the Red River? As George Woodcock wrote, “The condition of the Métis people has not changed materially as a result of this shift in the national mythology.” In other words, it’s easy to pick an exciting historical figure and put him on a T‑shirt. That kind of revisionism costs nothing in the way of reparations for “acquired” land or racism or double-dealing or fallacious incarceration — all of which Indigenous people continue to endure in the shadow of the Myth of Louis. “The popularity of the reclamations of Riel,” Braz writes, “suggests that we are more comfortable addressing national inequities and transgressions in the past than in the present.” The popular picture of Louis Riel is still more about the troubles at the Forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers in 1870 and in Saskatchewan in 1885 than about any current, complicated matters of reconciliation.

In 1869, the Red River Settlement at what is now Winnipeg was part of Rupert’s Land, effectively a British colony run by the private Hudson’s Bay Company. The HBC cut a deal with the Crown, and Ottawa bought the settlement. Surveyors were sent in to stake out the territory, a move the hunters and traders of mixed French and Indigenous ancestry didn’t care for. When Macdonald’s government dispatched William McDougall to act as lieutenant-governor, his party was stopped at the American border and Fort Garry was seized, in what’s now known as the start of the Red River Resistance. Riel set up a provisional government and settled in to negotiate with Ottawa, the HBC, anglophones, and a contingent of angry Ontario Orangemen (a literal “Canada First” movement). To cut a long, Homeric story short, the confrontation led to the execution of Thomas Scott, an Orangeman in Métis custody; exile for Riel in the United States; his spiritual awakening as a mystical Christian prophet (or the onset of his madness, depending on how one reads Christian mysticism); and his return north, to Saskatchewan, to lead the Métis in the North-West War fifteen years later, prompted by the slaughter of bison herds by settlers and the failure of Canada to live up to treaty obligations. Riel was captured and tried; his lawyers urged him to plead insanity, but he waved them away.

Was it treason? There’s a technical answer and an answer from the heart: the survival of the Métis was under threat, yet the execution of Scott was probably a mistake (as Riel himself later thought) and armed insurrection is a fraught way to block the construction of a railroad, as the nineteenth-century Indian Wars proved on the American Great Plains. You have Riel on one side and Macdonald on the other, and before long it’s obvious: this is a drama where the good guys (which?) and bad guys (who?) depend on your political underpinning and what you bring to the theatre, though you may change your mind about everything by the end of act 3.

Such was the thinking in central Canada in the 1960s, when John Coulter wrote two Riel plays and Harry Somers staged his opera Louis Riel (with an English and French libretto by Mavor Moore and Jacques Languirand). In line with the American civil rights movement, the mood was ripe for mythologizing the underdog of colour and in true Canadian fashion: with earnest stage productions. Soon a statue was erected in Regina, and Pierre Trudeau remarked at the unveiling, “Riel’s battle is not yet won.” But for Braz the interest in Riel has less to do with the story of the Métis and more to do with the history of a country that, since the Second World War, has been focused more on homegrown myths than on old tales of the British Empire: the flag changed, and so did the stories we told through art.

The Somers opera was restaged in Toronto in 2017 for Canada’s sesquicentennial. Although updated by the director Peter Hinton to make Macdonald a bumbling drunken boob, it is still in the Western tradition of modernist symphonic and vocal music with no Métis influence, meaning that it lacks fiddles and folk songs. By contrast, there’s the Manitoba Opera Company production of Li Keur: Riel’s Heart of the North, which puts fiddle music front and centre, making it something of an opera and musical theatre hybrid as well as an intentional work of cultural preservation (the librettist, Suzanne Steele, is Métis). I saw the show in Winnipeg in 2023 and witnessed a white audience member literally turning up her nose and announcing (quietly), “Whatever this is, it’s not opera.” Indeed.

Braz deals with Rudy Wiebe’s The Scorched-Wood People, a dense metafictional but deeply researched telling of Riel’s adult life, the Red River Resistance, and the North-West War that inexplicably places the Métis military leader Gabriel Dumont at the 1869 blockade at Red River (he wasn’t in fact there). But — fair play — it’s a work of imagination, not history, and Dumont is needed as a sidekick, a Sancho Panza to Riel’s Quixote, as Woodcock also observed. Braz’s point is that here again we have a Riel who strays even farther from accurate portrait into the league of Men of Literature. The same happens in Chester Brown’s Louis Riel, arguably a more historically robust account, but there he’s still a character in a graphic novel. The two statues of Riel in Winnipeg are also telling: Lemay’s 1971 sculpture, first erected at the Manitoba Legislative Building, shows a naked, tormented, and abstract Riel, but it was deemed a little too real and was eventually replaced by a supposedly more statesmanlike Riel. (With one hand on his sash, the other holding a sheaf of paper as if shaking it at Sir John A. Macdonald, he’s a more cartoonish character than anything drawn by Chester Brown, but he’s safe for tourists.) The tormented statue was moved behind St. Boniface College in 1995, and one must park illegally in a loading zone to see it properly.

Braz concludes that conveying the Métis story will remain difficult as long as Louis, or a Confederation-friendly version of him, is taking all the oxygen out of the room. He cites Maia Caron’s 2017 novel, Song of Batoche. Its central character, Josette Lavoie, is troubled by Riel’s religion, which she finds repugnant (after all, the Catholic Church, to which Riel was devoted, established residential schools in the West), and she fears that his execution of Scott will have serious consequences for her people. Because of Riel’s “Eurocentric identity,” Braz argues, writers like Caron “have such sweeping misgivings about him that it is bewildering why they feel compelled to write about him.” Why do they need him, he wonders. “What does he offer them that other early Métis figures do not?”

Perhaps it’s to demystify Riel in the eyes of a non-Indigenous population who’ve turned him into an easy out — a man to admire without having to dig into the real work of reconciliation and justice. “The inevitable question that is elicited by these works is how much can contemporary Métis distance themselves from Riel and still call the collectivity with whom they identify Riel’s people,” Braz writes. Perhaps a political reckoning will come, a change of order, a nod — all thanks to a Disneyfied Louis but with a move to a new story nonetheless. If so, it will come from artists.

Tom Jokinen lives and writes in Winnipeg.