As I write this, four of the five naked-eye planets — Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn — are all visible in the evening sky. Such celestial alignments often cause a bit of a stir on social media, for their supposed rarity (they’re not that rare) or their alleged influence on terrestrial events — of which there is none, though prominently visible planets do encourage skywatchers like myself to poke their friends and say things like “Look how bright Jupiter is!”

Some are surprised to learn that we can see any of the planets with the unaided eye, but indeed we can, as people have done since the dawn of history. For the Romans, Jupiter was the king of the gods. Venus played a key role in the ancient Mayan calendar; the second planet from the sun also gets a mention in the Book of Revelation. In Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well, Helena teases the cowardly Parolles by comparing his inclination to retreat on the battlefield to the retrograde motion of Mars.

Even before the invention of the telescope, people wondered if some of these wandering beacons might be worlds unto themselves. The ancient poet Lucretius pondered heavenly bodies inhabited by “different tribes of men” and “wild beasts.” Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, writing in the seventeenth century, wondered if Jovians would believe in earthlings; he suspected “that the inhabitants of Jupiter are too preoccupied in making discoveries on their own planet to daydream at all about ours.”

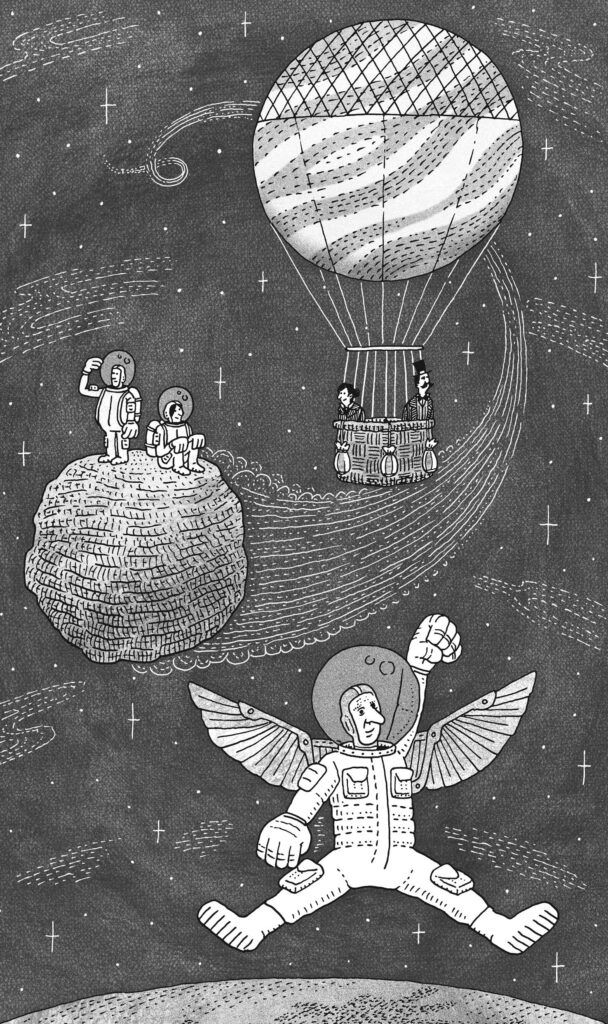

Collect those Air Miles here.

Tom Chitty

Imagining what these worlds might be like is one thing; getting to them is something else altogether. Human explorers have ventured only as far as the moon, which we last visited in 1972. Our robotic spacecraft, however, have sent back data and stunning images from every planet, even landing on a few of them. (Alas, no little green people; sorry, Monsieur de Fontenelle.) But we can certainly imagine voyaging to other parts of our solar system, and thanks to science we can anchor those imaginings in the known properties of these beguiling places.

That’s where John E. Moores and Jesse Rogerson pick up the story. Both are at York University in Toronto: Moores is a planetary scientist, and Rogerson is an assistant professor in astronomy and astrophysics. In Daydreaming the Solar System, they present a series of futuristic travelogues in which an intrepid spacefarer explores various corners of our extraterrestrial neighbourhood. Each chapter pairs one of their adventures with a discussion of what science has to tell us about the location in question. The book also features delightful drawings by the engineer turned artist Michelle D. Parsons and an eloquent foreword by the award-winning science fiction writer Robert J. Sawyer.

The traveller — their name, age, and gender are never specified — is simply “you.” (The authors explain in their afterword that this device is intended to make the stories egalitarian: when the day comes, anyone might have these adventures.) They are, of course, assisted by technology, yet some of this tech is distinctively retro. On Venus, for example, the traveller participates in “the annual Venusian Balloon Festival, the largest event of its kind in the solar system,” enjoying a mode of transportation almost two and a half centuries old (and much older, presumably, when these imagined events take place). They revel in nostalgia, wearing a mechanical wristwatch “instead of a modern digital chronometer.” The story continues:

There’s simply something romantic, you feel, about the trappings of the early era of aviation and ballooning. You have already put on the long pants, a light green peacoat and tall leather boots. As you stand, you pick up a plain leather cap and goggles, and grab a long, insulated, brown leather jacket lined at the collar with fur. Of course, these garments are not made from actual leather or fur, but are clever imitations that are much better at regulating your temperature and moisture.

Moores and Rogerson sprinkle ample physics into their adventure tales. As the balloon fest gets under way, for example, we learn that while Venus itself rotates once every 243 days (yes, its “day” is about two-thirds as long as a year on Earth), its upper atmosphere travels much faster, whipping around the planet in just a few days. How come? Because its thick clouds trap sunlight: “All that energy deposited at high altitudes must go somewhere, and that means spinning up the clouds and upper atmosphere to terrible speeds of hundreds of kilometers per hour.”

A surprise storm brings a brisk downdraft that takes the traveller by surprise, but they remain calm and ride it out — remembering that “in an atmosphere governed by buoyancy, what goes down must eventually come up.” With the storm over, the balloonists are rewarded with a spectacular vista, as the airships “turn on their burners to salute the sunset, giving a fiery glow from afar.” Some of the craft also deploy their own multicoloured lights, “like a neon-electric version of a thousand enormous paper lanterns, floating in the Venusian sky, truly a spectacular sight to behold.”

Venus is not even the book’s most exotic destination. The traveller visits Mars and Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, they go skydiving in Jupiter’s atmosphere, they get marooned on a comet, and more. In an episode that parallels the ballooning session on Venus, the traveller visits Saturn’s enigmatic moon Titan, which boasts an atmosphere thicker than Earth’s (albeit mostly nitrogen and methane). This provides another charming old school moment: with such a thick blanket of air, one can fly by means of a muscle-powered, flapping-wing glider, an idea that precocious inventors from Leonardo da Vinci to Otto Lilienthal have contemplated. Although the craft has a propeller, with a simple command, its “wings can lock into attachments on the arms and the articulations release to allow a human-powered flapping motion.” Artisans, we’re told, “have spent countless hours” designing the various moving parts, made from the latest high-tech materials. Then comes the science: it’s not just the thick atmosphere that helps lift our traveller; it’s also Titan’s weak gravity. Taken together, “wings that support a five-kilogram golden eagle on the Earth can hold up something 33 times heavier on Titan, say, 165 kg. By that calculation, human-powered flight is not just for elite athletes but for everyone.”

On the surface of Mars, meanwhile, we’re invited to ponder the fate of the robotic probes that paved the way for these grand adventures. What do we owe to the inert hulks of the Viking landers, the Curiosity and Perseverance rovers, and their metallic brethren? Perhaps they’ll become museum pieces, “preserved for future generations and revered.” Here I am crossing my fingers that the first to reach them will be more like Rick Steves than like Elon Musk.

In more than 200 pages, I caught just one mistake: The authors write that “from Earth we only ever see a crescent Venus, as it is illuminated obliquely by the Sun from Earth’s perspective.” Not so: when Venus is between us and our nearest star, it indeed appears as a crescent, but when it is on the far side of its orbit, it appears “gibbous,” as I have observed many times with my trusty Edmund Astroscan reflector.

Daydreaming in the Solar System is an entertaining and educational romp, but certain questions gnawed away at me. First, even if one day we’re able to undertake such journeys, should we? To some critics, the exploration and eventual settlement of other worlds too closely echoes the European colonization of our own planet. Others might dismiss such concerns as inane wokeism. These worlds are uninhabited, after all, with no indigenous people to harm (at least in our solar system), so why not just plow ahead? Moores and Rogerson have a more nuanced position, though we find it only at the very end, when they contrast two distinct perspectives — that of the “colonist” who sees the neighbouring planets as “simply resources to be exploited” and that of an “ecological” mindset, in which “the planets have inherent value just as they are.” Writing these stories forced Moores and Rogerson to confront “the conflict between perspectives, with the protagonist often taking the ecological side, in contrast to those who sought to use the environment for their own ends.”

Still one might ask, Why not just leave these worlds alone? With just a few paragraphs to go, we have our answer, echoing the comments made by the Apollo 8 astronauts, who on Christmas Eve 1968 saw Earth as a planet suspended in space for the first time: “Well, we are convinced that there is value in travel and in experiencing these places, that broadening one’s horizons allows us to see our own home and those who inhabit it with new eyes.” By getting to know these worlds, “we can see them for what they truly are and can imagine ways in which we can live in harmony with the many worlds of our universe.” If viewing Earth as a blue marble from 400,000 kilometres wasn’t enough to make us appreciate our home planet, a cynic might counter, why do we imagine that seeing it as a teeny speck from 50 million kilometres will do the trick? Sending humans to Mars may cost half a trillion dollars and could end up being as costly as the Apollo, space shuttle, and International Space Station programs combined. As for any of the other planets — well, the price tag for crewed missions would be, as they say, astronomical. Is it worth it?

I don’t want to sound like a party-pooper. Of course, it would be incredibly cool to cavort around the solar system, à la Buck Rogers, and maybe one day we will. But we might ponder our priorities. To their credit, Moores and Rogerson don’t explicitly rank space exploration above any other human endeavour; I’m sure they, like many readers, understand that humanity can have more than one goal. Or perhaps by the time we head to the planets, most of our earthly problems will have been solved — as suggested, at least implicitly, in the original Star Trek series. If that’s the case, what the heck. Bring on the (respectful) space tourists.

Dan Falk is a science journalist based in Toronto. His books include In Search of Time and The Science of Shakespeare.