Quick now: Who do you think is the most written about former prime minister of Canada? You might think it is Sir John A. Macdonald, given all the bad publicity he has received over the past decade. Perhaps Pierre Elliott Trudeau? In fact, they have hardly been examined compared with William Lyon Mackenzie King, who was prime minister for most of the 1920s and then from 1935 to 1948. His role in governing the country and in guiding its wartime administration and then the birth of the welfare state has won him far more scrutiny than any other.

Yet we hardly know him. I repeatedly came to this conclusion when reading Anton Wagner’s two-volume study of King as spiritualist. Almost fifty years ago, the historian C. P. Stacey, who had long toiled at writing excellent but obscure books on a variety of military and foreign policy subjects, published A Very Double Life: The Private World of Mackenzie King. It was a mild, very Canadian sort of succès de scandale, erupting in 1976 when ideas about religion and faith, to say nothing of government authority, were being challenged as never before. In that context, it was easy to find a market by making fun of Mackenzie King’s inner thoughts. Stacey’s success prompted many others to look into this salacious theme.

Now Wagner brings us The Spiritualist Prime Minister, a more serious and more comprehensive analysis. He must have laboured for decades to produce such a work. It is nearly encyclopedic in its documentation of how King approached the “other world.” But it is not simply in pursuing that concern that Anton Wagner wins a place on my Mackenzie King bookshelves. It is because he turns up all sorts of other illuminating details, such as King’s obsession with the German composer Richard Wagner and his operas.

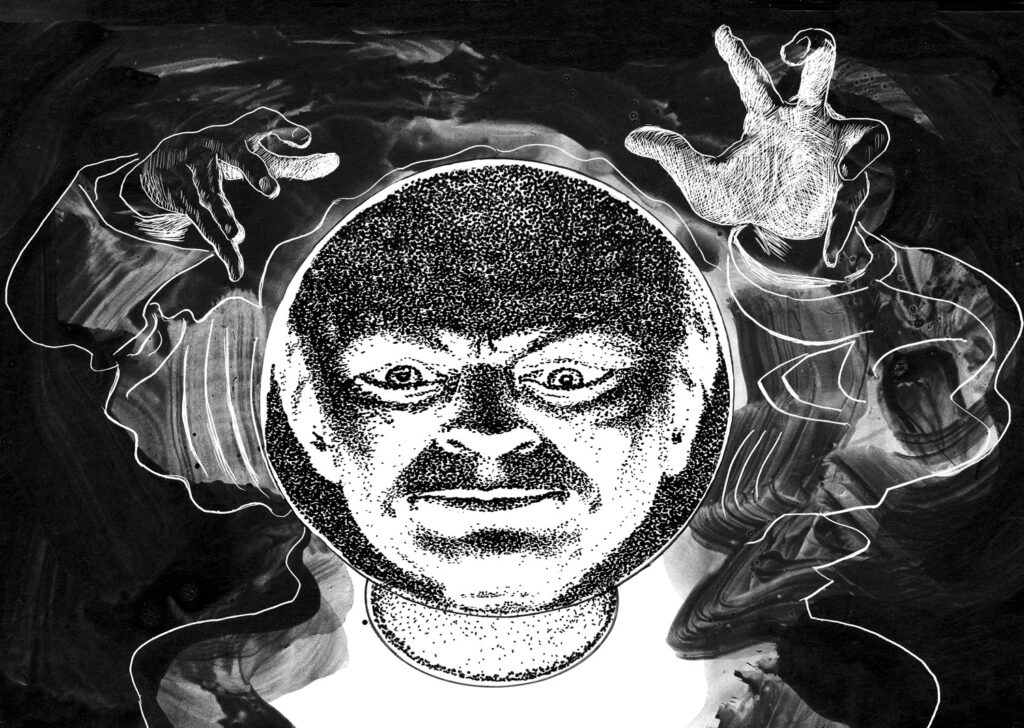

Our tenth prime minister looked for answers in all manner of places.

Silas Kaufman

In a long chapter that covers a multitude of topics before recounting King’s infamous meeting with Adolf Hitler in late June 1937, Anton Wagner describes King as “an avid follower of Wagner’s music on stage and on radio for four decades.” He wanted to feel the love, the exuberance, and, beyond the glory of the works, the presence of God. Devotion to these operas was an enthusiasm he had in common with the führer. “I spoke of Hitler living in the atmosphere of Wagner & his myths & beliefs,” King would say of their encounter. “I believe he believes in reincarnation and probably believes himself to be Siegfried reincarnated.”

For all the writing that has been devoted to this visit, it had no impact on King’s policies. Whatever hopes he might have cherished that Hitler would be pacified, King kept boosting Canada’s defence budget significantly. He had done God’s work in meeting the chief Nazi, but King knew very well that war was coming.

Of course, we now know all this because King bared it in his journal. The diary he kept for his private uses practically every day is now online, providing universal access to about 30,000 pages and over 7.5 million words. King apparently also kept two separate binders that contained a record of his most vivid séances. These were burned by his literary executors in the mid-1970s. Most of us just go to bed to forget our mundane lives. King, the prime minister, stayed up to remember.

Mackenzie King did not hide his interest in fortune telling, spiritualism, and what he vehemently believed was the emerging science of psychical research. He underwent phrenological examination as a boy (his mother asked) and again as a young adult, and early in his career he talked freely to Sir Wilfrid Laurier about spiritualism (he was not spurned). Winston Churchill knew about King’s passions, as did George C. Marshall, the chief of staff of the United States Army. King revealed his interest to Sir John Dill, the chief of the British Joint Staff Mission in Washington, who turned out to be an equally dedicated spiritualist. The prime minister’s circle of friends in Ottawa, such as his confidante Joan Patteson and his good friend Arthur Doughty, the eminent scholar and dominion archivist, routinely attended séances with him. It was not a double life. In fact, according to Anton Wagner, King’s spiritual side was woven into everything he did.

Wagner, much better known for his contributions to documenting the history of the Canadian theatre and as a documentary filmmaker, came to this subject late in his career. He undertook his King studies by writing a doctoral dissertation at York University on King’s passionate interest in the arts and in artists, as well as in architecture and cultural matters generally. Richly documented, that work acted as a springboard to this exploration of his spirituality.

Mackenzie King could have done anything with his life. He could have translated his successful stint as a journalist in the mid-1890s into a spectacular career in the press. He could write, had a good mind for public policy and politics, and could easily have rivalled Joseph Atkinson for the top job at the Toronto Star. In a pinch, he probably could have done the same for a conservative newspaper.

King could have continued his life as a public servant as well. In 1900, he was named a deputy minister at the impossible age of twenty-six, and he could have carried on — perhaps changing the face of the bureaucracy as a result. Or he could have become a practising lawyer. He earned his degree at the University of Toronto but never qualified to stand at the bar. With the legal training plus his later experience as a labour negotiator and consultant to the Rockefellers, he certainly could have put his talents to use in a stimulating and financially rewarding career. Of course, he could have opted for the academy. He earned a doctorate from Harvard in 1909 (the only prime minister to have one until Mark Carney took office in March) and turned down multiple job offers before confining himself in Ottawa. As in journalism, bureaucracy, and law, King would have climbed institutional rungs and installed himself as the president of the university of his choice. Perhaps he could have joined the clergy? King was an ardent believer and daily reader of the Bible — a man convinced that God had chosen his destiny. He could be preachy.

Instead King chose the most unpredictable profession of all, trusting that his fate was to enter Canadian politics so as to save the country from whatever disasters could visit its shores — and from the Conservative Party. He ran for a seat in Parliament in 1908, representing Waterloo North, and served as the country’s first labour minister. He was defeated in the 1911 election. Undaunted, he ran in a Toronto riding in 1917 and was again beaten. It was a harrowing year in which he also lost his mother. He was feeling sick and aimless, but he had money and independence. He was not married and had no children.

At forty-three, he had to make a choice and decided to stick with politics and live up to his mother’s hopes that he become the prime minister. In 1919, shortly after winning the Liberal Party leadership, he searched for spiritualists and had a session. It would be the first of 130 such encounters with mediums of all sorts, as well as fortune tellers, palmists, astrologers, graphologists, phrenologists, and psychic investigators, that King recorded in his diary (and there may have been others) over the next thirty years, about one every three months, right until his death in 1950. This was not a passing interest, contrary to what many have believed (including me).

Wagner divides his admirably exhaustive exploration of King and his spirit world in two. The first volume sets a broad context for King and his psychic pursuits, offering chapters on a variety of subjects, not least on the widespread popularity of spiritualism in the United Kingdom. It also explores King’s obsession with magnetic and electric “sex currents.” For King, these were evidence that outside forces were trying to control him, and he confided in his diary that he was often sexually aroused when speaking to large crowds. The second volume explores in commendable detail King’s particular interactions with a wide range of mediums — all women, as it turned out.

Wagner reveals King as a lonely man. He was on a pilgrimage, searching for God, eagerly trying to discern providential clues. He saw them in the alignment of the clock’s hands, visions perceived in a perfect sphere, the lines etched in his palms, astrology, or a chance reading in a random book excerpt. King was also looking for personal reassurance: the trust of his friends, members of his cabinet, or his caucus was not enough.

Two things are clear. The first is that King took the trouble to journal impressions that could have been very common to anyone. Most of us love our mothers and think of them kindly; we just don’t write that down. The second is the absence of evidence that King ever changed his mind as a result of his psychic encounters or that his government’s policies shifted course because of the advice he heard from the other world.

Wagner describes the scene when, during a séance in October 1945, the PM asked his departed friend Franklin D. Roosevelt whether nuclear secrets should be shared with the Russians and also requested advice on a wide variety of domestic matters. What is striking is that no answer from “beyond” was secured other than that the subject would be raised at an upcoming lunch.

In fact, King was more often than not disappointed by what he heard. This can hardly be surprising: the people who served his wishes were talking to the same people he knew and were reading the same newspapers. His mediums clearly took pity on him (they also took his money, as Wagner shows) and quietly encouraged him. Yes, he was on the right track; yes, the deceased people he loved and admired thought he was doing a good job. Few of us can exist without support for long; it’s just that King needed additional doses of reaffirmation from beyond, roughly every season.

In an age when tolerance for such eccentricities was perhaps diminished, King’s habits may have been frowned upon. As Wagner explains, Canada was never a very fertile territory for the sort of spiritualism the prime minister engaged in. Fifty years ago, the estimable scholar Reg Whitaker was given special permission to consult King’s diaries and came away convinced that he was “quite crazy.” H. S. Ferns, the British author who had worked for King in the early years of the Second World War, declared him “foolish and childish.” Even the popular journalist Pierre Berton told a national television audience in 1978 that King was “a certifiable nut.” People who worked for King also often resented his manner, describing him as essentially soulless.

As we enter the second quarter of the twenty-first century, when polls show that roughly half of adults believe in ghosts and spirits, King’s sincere spirituality should be greeted with sympathy and, perhaps, a bit more understanding.

Patrice Dutil is a professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at Toronto Metropolitan University. He founded the Literary Review of Canada in 1991 and wrote Sir John A. Macdonald & the Apocalyptic Year 1885.